Pledging To Defend South Korea With Nuclear Weapons, Washington Assuages Seoul’s Fears of Attack From North

For now, America will send a nuclear submarine — not nuclear warheads — to South Korea.

On paper at least, President Biden is ready to declare nuclear war in response to a North Korean strike on South Korea.

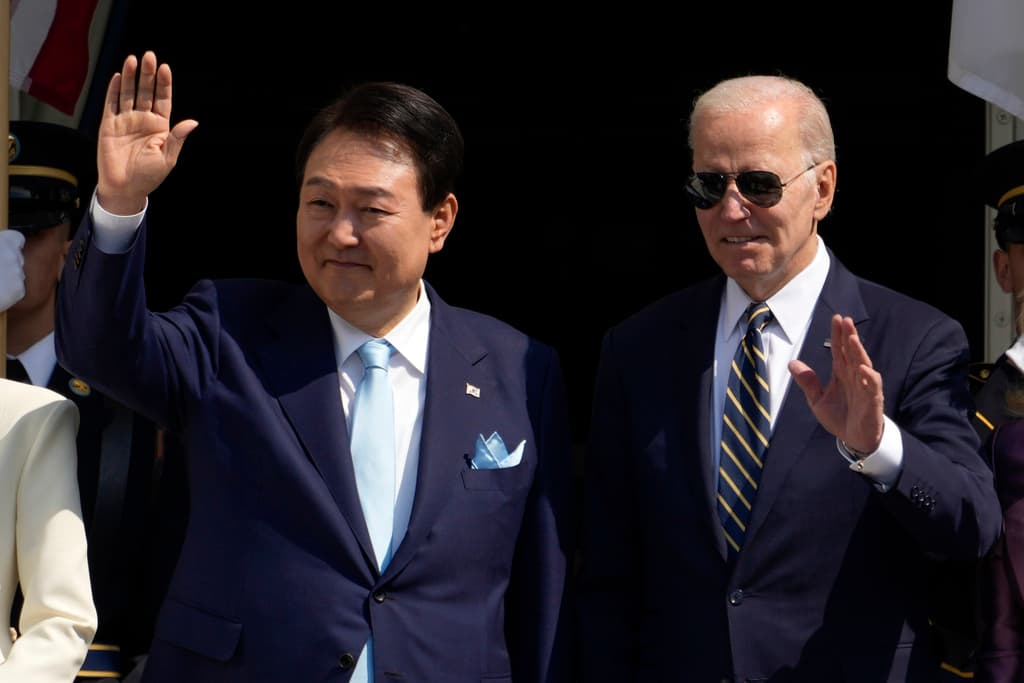

That much seemed clear from the joint declaration that he and President Yoon of South Korea signed Wednesday at the White House, climaxing a full-dress state visit that may mark the beginning of a new era in the American-South Korean alliance.

The promise of swift reprisal against the North, coming after the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, has ordered more than 100 missile tests since last year, seemed unequivocal.

As laid out in what’s called the Washington Declaration, “Any nuclear attack by the DPRK against the ROK will be met with a swift, overwhelming and decisive response,” using the initials for Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Republic of Korea, the formal names of North and South Korea.

Just in case there was any doubt as to the meaning of the statement, it declared that “the U.S. commitment to extended deterrence to the ROK is backed by the full range of U.S. capabilities, including nuclear.”

The next sentence, though, indicated those fire-eating words represented a compromise, maybe even a disappointment to the Koreans, whom polls show want America to position American nukes in South Korea, from which President George H.W. Bush withdrew them in 1991.

“The United States will further enhance the regular visibility of strategic assets to the Korean Peninsula,” it said, “as evidenced by the upcoming visit of a U.S. nuclear ballistic missile submarine to the ROK.”

A submarine, though, is not a weapon. Without saying so, the statement ruled out any possibility that Mr. Biden would reverse that historic decision. The omission of the word “nuclear” from the types of “strategic assets” the Americans might have in mind was hardly an oversight.

Nor was a word said about South Korea developing its own nuclear weapons — something that polls show upward of 60 percent of Koreans would like to see. South Korea, which has built more than 30 nuclear power plants, has the technology to match North Korea as a nuclear weapons state, but the Americans are fearful of a nuclear arms race in which Japan and the Republic of China on Taiwan would also make nukes.

There was no doubt, though, that the Washington Declaration was crafted to answer deep South Korean concerns about the American commitment while Kim Jong-un waxes ever more menacing, mingling rhetoric with missile tests.

The declaration “looks like a significant win-win for both the U.S. and the ROK,” a retired senior American diplomat, Evans Revere, who served for years in the American embassies at Seoul and Tokyo, said.

Just as important as the “strong reaffirmation of the U.S. extended deterrence commitment,” he said, was “the launch of the nuclear consultative group” providing for constant dialog and cooperation between Americans and Koreans.

“Seoul now has for the first time a mechanism to discuss nuclear weapons-related planning with the United States,” Mr. Revere told the Sun. “This is a very big deal after the damage done by President Trump to South Korean confidence in the alliance and to the credibility of the U.S. deterrent commitment.”

“This new agreement,” Mr. Revere said, “does much to repair that damage and restore Korean confidence that the United States stands ready to defend the ROK with all of the weapons in its arsenal.”

The Americans were eager to demonstrate their commitment beginning with a full-dress welcoming outside the White House featuring the Marine Corps band and a fife-and-drum contingent in colonial-style uniforms. Significantly, after their summit inside the White House, it was Mr. Yoon, not Mr. Biden, who announced the salient points in the Washington Declaration.

“Our two countries have agreed to respond to North Korean attack using the full force of the alliance,” he said, and just to make sure the Americans and Koreans are ready for a “nuclear crisis,” he added that they have agreed to conduct still more military exercises in addition to the drills they’ve been performing for weeks.

The summit also suggested a kind of grand bargain between the Americans and Koreans. Mr. Biden in his remarks pointedly said that South Korea was “working with our ally Japan” and that they had also discussed our “commitment to the Taiwan Straits” and the South China Sea.

Those are all hyper-sensitive topics, considering that Korea has often been at odds with Japan and is reluctant to get involved in conflict between America and Beijing over the South China Sea and Taiwan, the breakaway Republic of China that Beijing vows someday to recover. Mr. Yoon also shared common cause with the Americans on aid to Ukraine after having tried to avoid taking sides against the Russians.

The display of American-Korean unity, celebrating the 70th year of the formal alliance that sprang up after the signing of the truce with South Korea 70 years ago, on July 27, 1953, was sure to draw a nasty response from North Korea in the form of more missile tests. Mr. Kim is expected sometime soon to order the North’s seventh underground nuclear test — its first since September 2017.

The show of unity as seen in the meeting between Messrs. Biden and Yoon should dissuade him, though, from any notion of attacking the South.

“The U.S. has already made clear in recent months that a North Korean nuclear attack would result in the end of the North Korean regime,” Mr. Revere said. “That’s a powerful message, and the new understandings reached between Seoul and Washington make it even more so.”