Patrick Henry and the Lesson of the Loyal Opposition

John Ragosta, in a brilliant recuperation of Henry’s reputation and a nod toward the politics of today, shows that like Washington, Henry feared that partisanship threatened the foundations of the republic.

‘For the People, For the Country: Patrick Henry’s Final Political Battle’

By John Ragosta

University of Virginia Press, 304 pages

In 1799, George Washington, worried about the survival of American democracy, wrote to Patrick Henry urging him to come out of retirement and run for the Virginia House of Delegates, to which Henry was elected on March 4, 1799. He served hardly more than three months, dying on June 6.

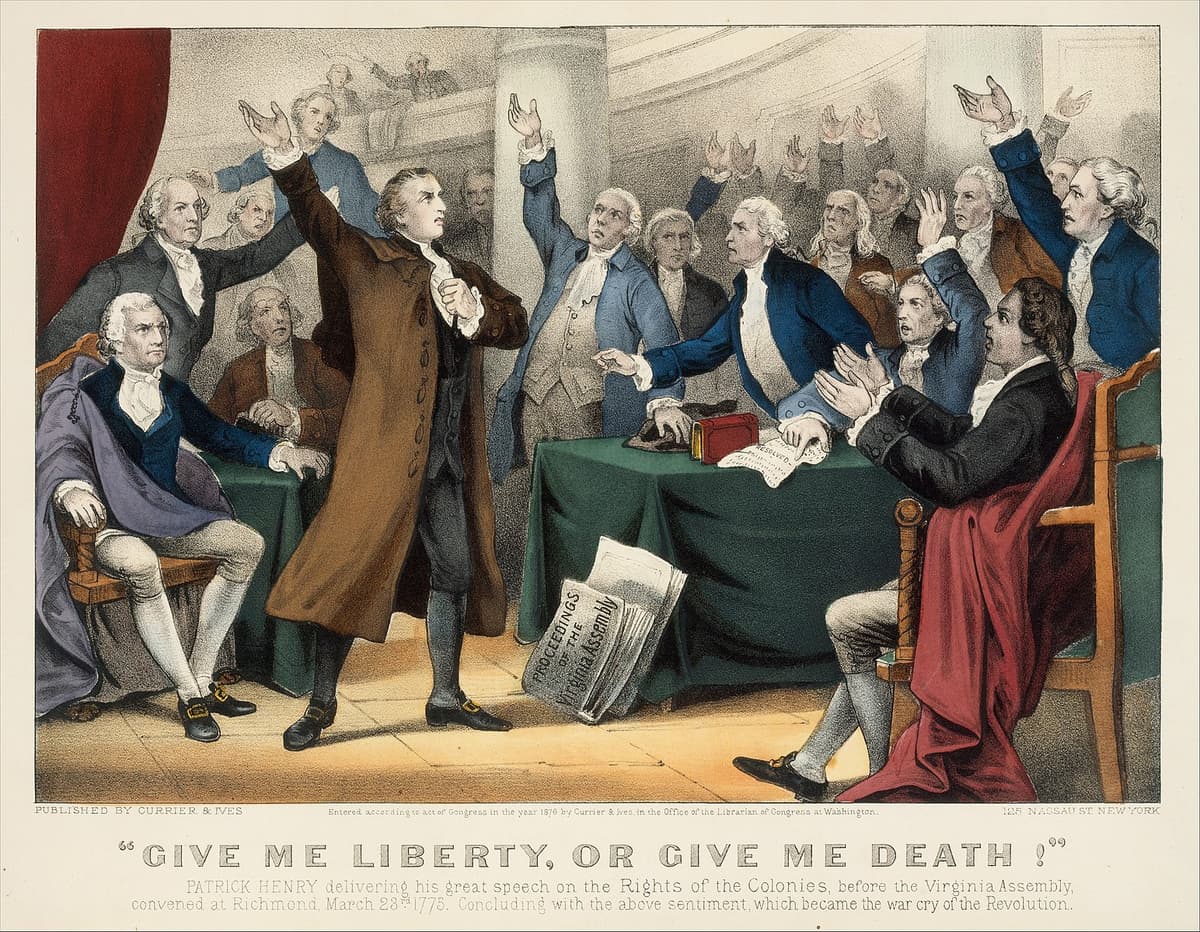

Henry, perhaps the greatest orator of the American Revolutionary period, famous for his ringing defiance of British rule — “Give me liberty, or give me death” — opposed ratification of the Constitution and has often been promoted as the progenitor of the states’ rights doctrine.

So why would Washington, alarmed at attacks on federal authority in the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions (1798) by formidable adversaries such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, turn to Henry? Washington and Henry had not communicated since the hard feelings engendered by the ratification battle a decade earlier.

Washington knew his man as a believer in majority rule. Henry’s qualms about the Constitution — he feared the power of a central government too far removed from the people — remained, but the lawful government must be respected, and Washington knew that Henry still had the profound respect of their fellow Virginians.

Generations of misinformation propagated by Jefferson and his allies pointed to Henry’s latter-day support of Washington and the Constitution as the result of senility, and highlighted profits Henry supposedly made from the financial policies of Alexander Hamilton — to name just two of the allegations that Mr. Ragosta demolishes. In a brilliant recuperation of Henry’s reputation, the author emphasizes Henry’s pivotal role as a believer in a loyal opposition.

Like Washington, Henry feared that the partisanship of Jefferson’s party threatened the foundations of the republic, and that the new nation might break up in Civil War, preventing the peaceful transfer of power in the forthcoming election of 1800.

Mr. Ragosta surveys different accounts of Henry’s last public speech, attended by a huge audience that realized it was a historic occasion. The biographer recounts Henry’s declaration of support for the federal government and his abiding belief in the peaceful transfer of power under a lawfully established Constitution.

Mr. Ragosta shows that certain Founders of the new nation like George Mason suggested they might resort to violence over their disagreements with certain constitutional provisions, which is why Washington urged Henry to come out of retirement to wield his enormous influence on the electorate in the crucial state of Virginia — otherwise controlled by Jefferson and Madison.

In the decade after the ratification of the Constitution, Henry had refused offers of high office made by the Washington and Adams administrations, stipulating that he would not become active in political and government affairs again unless the nation was in crisis. That crisis, Washington assured Henry, had arrived.

The 1799 climacteric to the contentious politics during the Adams administration looks a good deal like today, Mr. Ragosta argues in his Epilogue. He cites Henry, who believed we could only govern in the present, and the republic could only endure, by understanding what happened in the past, which meant accepting electoral defeat and the outcome of elections. In 1799, too many of even the wisest politicians seemed to think otherwise.

One of the most intriguing parts of Mr. Ragosta’s book is his analysis of Jefferson’s peace offering in the first inaugural address: “Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names, brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

Mr. Ragosta suggests that perhaps Jefferson was offering more than just “political pablum.” Just maybe Patrick Henry’s putting aside his own rancor over ratification of the Constitution to unite with Washington had an impact on Jefferson, who joined Madison in moving away from their shrill advocacy of states’ rights.

Jefferson never credited Henry with demonstrating what it means to be in the loyal opposition. In fact, Jefferson, like Woodrow Wilson, could enunciate the highest principles and then turn around to do the most mean-spirited things — and yet, in Mr. Ragosta’s compelling narrative, Henry seems indispensable to understanding Jefferson’s change of mind, regardless of whether Jefferson realized it.

Mr. Rollyson, author of “American Biography,” is at work on “Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History.”