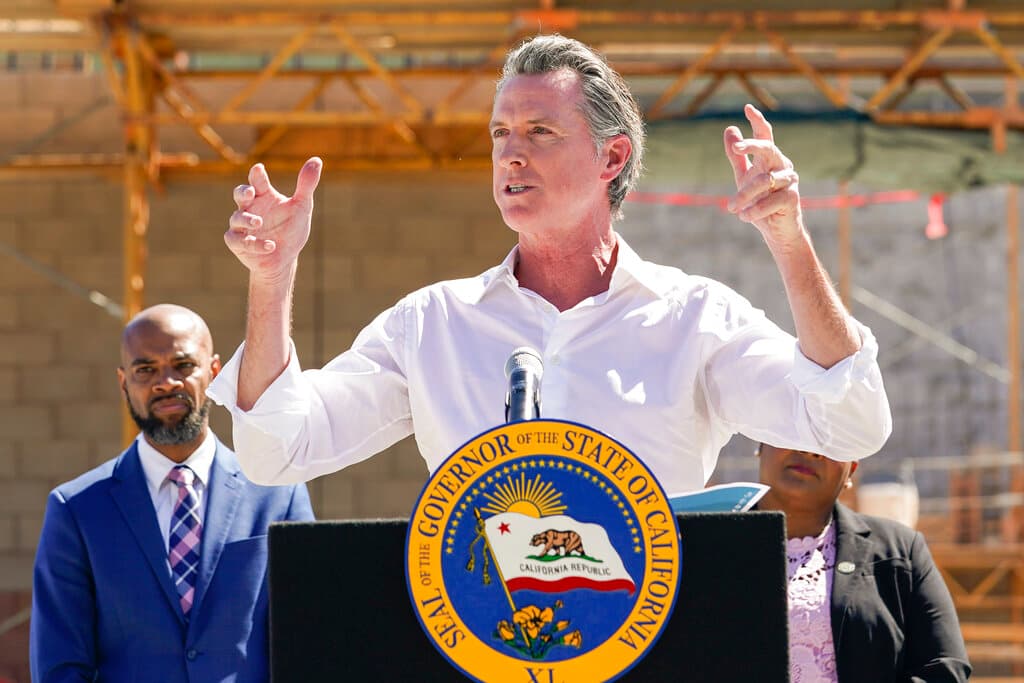

On ‘Safe’ Injection Sites, New York Can Learn from Governor Newsom

The California governor hit pause on an approach whose benefits are unproven — and whose risks are high. The message is much needed at New York.

Governor Newsom of California has uncharacteristically veered from the progressive policy playbook by vetoing a bill that would have legalized so-called “safe injection” sites in the Golden State. Mr. Newsom said that such “harm reduction” facilities, where addicts can inject fentanyl and heroin under medical supervision, lacked “well-documented, vetted, and thoughtful operational and sustainability plans.”

Please check your email.

A verification code has been sent to

Didn't get a code? Click to resend.

To continue reading, please select:

Enter your email to read for FREE

Get 1 FREE article

Join the Sun for a PENNY A DAY

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

100% ad free experience

Unlimited article and commenting access

Full annual dues ($120) billed after 60 days