New Iran Nuclear Deal Looks Weaker Than First, and Congress Needs To Strike It

Based on what we know now, Congress should move to disapprove the deal and block the president from waiving any sanctions on Iran.

In the next few days, expect an announcement that the Obama administration’s nuclear agreement with Iran has been brought back from the dead. Months of discussions between the Biden team, Russia, China, France, Britain, Germany, and Ebrahim Raisi’s terrorist-sponsoring Iranian government have produced a revised version of the deal that President Trump disemboweled four years ago.

This revised deal, reportedly featuring light restrictions on Iranian nuclear activities that will expire quickly, appears to be substantially weaker than the 2015 agreement. Effectively, the West will be agreeing to this trade: dropping economic sanctions on Iran in exchange for three to five years of limits on a small set of Iranian nuclear weapons-related activities.

When the deadlines on the minimally restricted Iranian behavior have passed — probably well before the end of this decade — Iran will have de facto international approval to pursue a nuclear weapons program and President Biden will have pledged that the U.S. won’t use sanctions to try to stop it.

The announcement of this agreement should be met with great skepticism, concern, inquiry, and, most importantly, disapproval on the part of Congress. Based on what we know now, Congress should move to block the deal and the president from waiving any sanctions on Iran.

That path — review and disapproval — is established in American law. Under the 2015 Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act, which passed with overwhelming support from both Republicans and Democrats, any agreement with Iran regarding its nuclear weapons program must be submitted to Congress for review and possible disapproval.

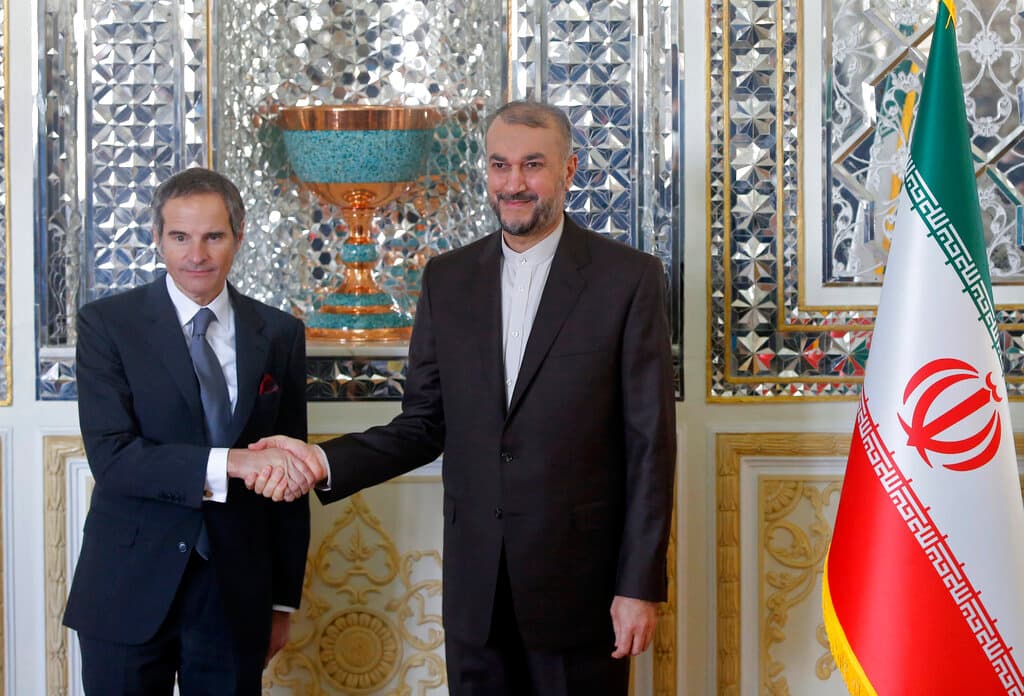

The law specifies that the entirety of the agreement — including any related side deals with other countries or organizations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency — must be submitted for congressional review. This includes any specific understandings directly with Iran.

The Biden administration has indicated publicly that it is considering lifting the terrorism designation for the Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps, whose agents nurture and support terrorist organizations across the Middle East. This agreement, whether in writing or verbal, is clearly part of the Iran nuclear deal and under the law must be disclosed to Congress.

During the congressional review period the president cannot waive any sanctions on Iran, depriving him of any unilateral ability to reward Iran. The sanctions regime that has contained Iran was driven by Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, for many years. It is only right that the attempted removal of that sanctions regime by the president should withstand review by the legislative branch.

There have been murmurings that the Biden administration will assert that the current agreement is not new, merely a redux of the previous agreement, and therefore submission to Congress is not required. The law is clear, however, and any attempt by the administration to avoid congressional review should be met with bipartisan outrage and severe consequences, including the withholding of funds, approvals of nominations and the withdrawal of presidential authorities granted by Congress.

Per our Constitution, the job of the president is to manage the day-to-day exigencies of the nation’s position in the world. It is necessarily a short-term view, and one appropriate for a public servant in a four-year term.

Congress was designed to take the longer view of America’s interests in the world. Will the president’s trade-offs of today be good for American national security in five or 10 years, after he has surely left office? In the Senate in particular, where members serve longer terms than the president, that answer to that question will be in the negative.

In 2015, Senators Schumer and Menendez, both Democrats, voted to disapprove President Obama’s original nuclear deal with Iran. Today, they are respectively the majority leader of the Senate and the chairman of the powerful Foreign Relations Committee.

Last month, Mr. Menendez took the Senate floor and expressed grave reservations about the negotiations with Iran: “‘Whether or not the supporters of the agreement admit it, this deal is based on ‘hope’ — hope that — when the nuclear sunset clause expires — Iran will have succumbed to the benefits of commerce and global integration. Well, they have not…. Hope is part of human nature, but unfortunately it is not a national security strategy.”

With a little bit of charm and goodwill, Republican senators should be able to persuade Messrs. Schumer and Menendez to put the long-term interests of the American people front and center and move to disapprove this new, even weaker Iran nuclear deal.