Meditating On, and With, David Lynch

In 2006, this author traveled from Berlin to Jefferson County, Iowa to interview the iconic director at Maharishi Vedic City, a mecca for adherents of Transcendental Meditation.

The four children of the iconic film director David Lynch, who passed away last week, announced that they will hold a worldwide meditation session in honor of their father on Monday.

“David Lynch, our beloved dad, was a guiding light of creativity, love, and peace. On Monday, January 20th—what would have been his 79th birthday—we invite you all to join us in a worldwide group meditation at 12:00pm NOON PST for 10 minutes,” his children Jennifer, Austin, Riley and Lula Lynch wrote on X on Saturday afternoon.

Mr. Lynch was a devout practitioner of Transcendental Meditation (TM), and a spokesperson for the organization that teaches the technique, which was developed and brought to the United States by the Indian guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in the 1950s, and made popular by prominent adherents like the Beatles and the Beach Boys.

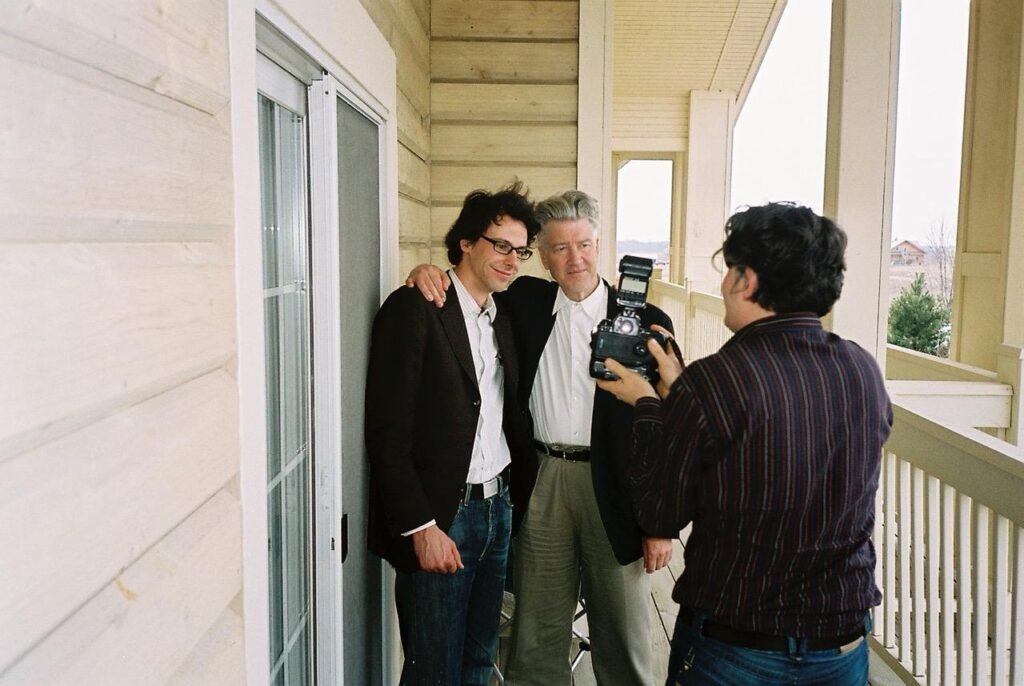

I met Mr. Lynch in 2006 and interviewed him about his meditation practice for a German newspaper in a tiny town in Jefferson County, Iowa, called

Maharishi Vedic City. I was a young writer and it was my first feature interview with a celebrity, or rather, with a legendary artist and master of his craft.

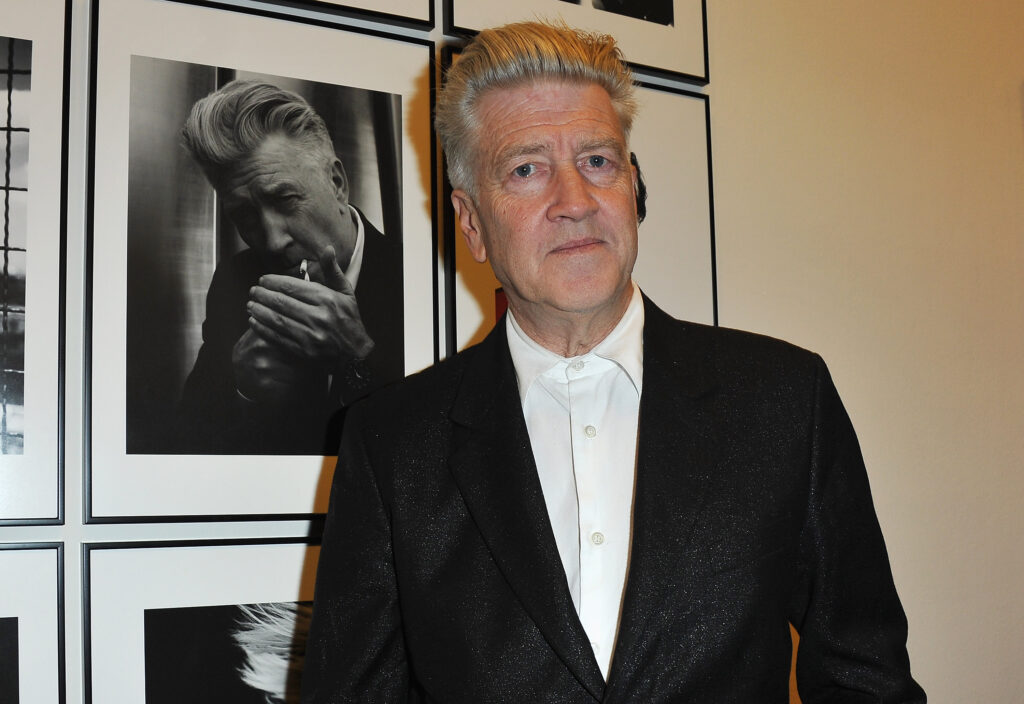

Mr. Lynch is rightfully considered one of the greatest film directors. Like Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, Billy Wilder, or Martin Scorcese, to name only a few, he pioneered a singular style and story telling. He dared to make movies the likes of which had never been seen before, and yet they captured and reflected their time, be it the 70s, 80s, 90s, or the early 2000s.

His oeuvre, unique like the books by Franz Kafka or the paintings by Francis Bacon, is twisted and unparalleled. Mr. Lynch set and created his own mood.

His first film, “Eraserhead” from 1977, a surrealist, black and white horror movie, was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” He was nominated for four Oscars for “The Elephant Man,” “Blue Velvet,” and “Mulholland Drive.” In 2019 he received the Academy’s lifetime achievement award.

His biggest commercial success was the 1990 ABC television series “Twin Peaks,” a murder mystery, co-written and co-produced by Mark Frost, about an FBI agent who searches for the killer of the high school student Laura Palmer in a small, foggy town in the Pacific Northwest. The hauntingly beautiful film score, composed by Angelo Badalamenti, is much like Nino Rota’s “The Godfather’s Waltz,” one of the most memorable soundtracks in the history of film. The series was a cultural sensation, but was canceled after only two seasons after it became too confusing and bizarre for ABC’s mass audience.

In 2006, Mr. Lynch was finishing what would be his last movie, “Inland Empire.” I was living in Berlin, Germany, with my boyfriend at the time, David Sieveking, who was also an aspiring film director. After winning an award for a short film, David was invited to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, where he attended a seminar about film editing given by his hero, Mr. Lynch. But the visionary director did not talk about editing; instead he gave a lecture about Transcendental Meditation. My ex was disappointed at first, but then intrigued. The technique is supposed to promote stress relief and good health, and its practitioners claim they can reach higher states of consciousness. You can even take courses on “yogic flying.” David was suspicious of these life-changing promises, and decided to make a documentary about Maharishi’s movement, which had its own small town in Iowa.

I had published my first book, and working on a second novel, I was wrapped up with my own stories. But that changed on the day David told me, he was flying to Iowa to visit the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Vedic University, because Mr. Lynch was going to be there for a week.

To get an interview with Mr. Lynch was not an easy task, and to help David, I pitched the story to a major German newspaper that ran a feature interview section in its weekend edition. The editors said that if I could get to Mr. Lynch, they’d print my story. I remember getting on the plane in Berlin, not knowing if Mr. Lynch would speak to us. But lo and behold, when I arrived in Iowa, David, who was already there, had received the confirmation. We would meet the film legend the next morning at the Rukmapura Park Hotel.

I was nervous, I won’t lie. The journalist in me longed to catch the master off guard, to provoke him, to get him to reveal something new. But the artist in me was filled with admiration – and shyness.

Maharishi Vedic City is a strange place, almost like a film set in one of Mr. Lynch’s surreal movies. Around 277 people lived there in 2020, according to the most recent census. Twenty-five years ago, when I visited, the town was arranged in ten circles, laid out in the concept of a “Vedic City” conceived by Mr. Maharishi himself. All the houses are painted in off-white colors. The streets are clean like they are in Switzerland. Everything appears light, spacious and neat.

The hotel room, where we waited for Mr. Lynch, was flooded with sunlight. I remember the carpet had a pattern of yellow roses, and a vase with real yellow roses stood on top of a fireplace. What a contrast, I thought, to the dreamy darkness Mr. Lynch had created in his movies.

The director arrived punctually with a small entourage of people, who worked for the Transcendental Meditation organization. He wore a suit, and he was visibly uncomfortable. Many artists don’t like giving interviews. He told me, he was visiting the vedic city to receive Panchakarma, an ayurvedic treatment of hot oils and an organic diet.

“I was talking to someone recently who said one day the earth will be polluted, the air will be polluted, the water will be polluted and then Panchakarma will be a necessity not a luxury,” he said. “And so it’s a way of purification. I will be finished this afternoon and go back to Los Angeles tomorrow, hopefully a little cleaner than before.” When he spoke his hands moved as if he were playing an air piano. The spark in his eyes, which I was lucky to catch a few times, revealed his childish curiosity and his sense of humor. He was a shy man, soft spoken, and kind.

He began meditating in 1970, when he was a student at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. “I had everything I thought I ever wanted.” He told me. The dean of the school at the time, Frank Daniel, was supporting him to make his first film, “Eraserhead”, and had provided him with a location and equipment, two 35 mm cameras, cables, lights. “And one day I was leaning on the table thinking I should be the happiest person in the world and I realized that there was mostly this emptiness in me.”

His sister recommended Transcendental Meditation and it changed his life.

“Two weeks later my wife says, what’s going on? I was quiet for a moment. Finally I asked, what do you mean? She said, this anger, where did it go? Because I was taking it all out on her. It had just lifted. And that’s a very real thing. That is a very real thing. The anger was there and it just lifted away. The same way with depression and sorrow. And this fear. Fear. Fear.

Fear of the unknown, how it’s all gonna fall, that’s running through the world and manifests in all different ways. And you’re right in the middle of it and you don’t know and blame other people for something that is really just you. The anxieties. They start lifting away. You become calm.”

We spoke about his David Lynch Foundation for Conscious Based Education and World Peace. He aspired to introduce Transcendental Meditation in schools around the United States. He wanted to raise “seven billion dollars” to allow any student to start learning “how to dive within and get on the fast track to enjoying life.” He believed that the technique could help them develop their “full potential.”

“Stress is killing so many students. And this blows the stress away,” he said, smiling. “They start appreciating others like they appreciate themselves. Appreciating everything. It sounds so goofy. But it’s really pretty thrilling.”

Mr. Lynch was born in Missoula, Montana. His father worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and his family moved quite a bit, following the various assignments his father would get across the country. He was raised as a Presbyterian. I asked him if Transcendental Meditation had become a form of religion for him.

“No, it’s not a religion,” he said defensively, almost as if he didn’t want to be boxed into something. “Now, I was a Presbyterian.” He went on. “My parents wanted me to go to Sunday school. So I went to Sunday school. And around 14, I didn’t see the result. I saw living one way on Sunday and a different way the rest of the week for a lot of people. And I wasn’t getting what I thought I wanted and I asked not to go anymore. And bless my father’s heart, he said, you don’t have to go to church anymore until you want to go. But people who are religious meditate, all religions, and they get more understanding from their religion, more appreciation. In my mind anyway, all religions are rivers flowing to the one ocean. And I’m diving in there my way. And I’m getting wet with that and I like it!”

He liked, he said, that one could add the technique “to your life and go about your business. You don’t join up with anything.” For many years, he didn’t want to publicize his practice.

“When people hear, oh you’re a meditator, oh, you’re with Maharishi, they start looking at your films that way. I just wanted to keep it quiet. But now the world is changing.” He felt people, and especially children, were more distressed, plagued by learning disorders, and the world had spiralled into chaos and wars, and so he longed to promote what he believed to be a medicine of peace.

“And what’s her name? Reese Witherspoon wins this thing and wants world peace and everybody gets a big laugh. World peace. Everybody wants world peace. Nobody believes that there can be world peace. It’s a nice idea. Like a sweet little old lady idea. It’s meaningless. It’s never gonna happen. And we live in this hellhole. And we think it’s gotta be this way. And there’s a lot of suffering everywhere. And this peace isn’t a stupid thing. It’s not a doily like I say, it is not a doily. And Maharishi has this plan. It’s a science and a technology for peace. Based on Vedic Science. Peace isn’t just the absence of war. Peace is the absence of negativity.” He looked like someone who had found a definitive answer.

But there was a quote of his that I had written down on my notepad that expressed, much like his films, that he believed in life’s unsolvable mysteries. And I read it to him: “I don’t think people accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense. I think it makes people terribly uncomfortable. It seems like religion and myth were invented to make sense out of it.”

He leaned back in his chair, his hands resting on knees. “I don’t even understand what I said,” he told me and paused. “But it does make sense! Maybe not in the way they think. But it begins to make more and more sense.”

One has to know his films to understand how weird it was to hear Mr. Lynch tell you that life makes sense. His movies don’t. And he refused, in countless interviews, to staple them with any kind of straightforward meaning, moral, or message.

I insisted, and asked again, how did he combine his dark, mysterious art with this meditation technique that seemed to offer all the answers.

“It’s a weird thing,” he said. “The mystery of life is very beautiful. But mysteries are meant to be solved. As I say, we are like detectives. Whenever there’s darkness the mind gets kicked in and we wonder what’s there. We look here and we find a clue and we look there and we find a clue. And it all kind of feels like there’s more than meets the eye. And instead of it being frightening, it’s sort of thrilling. Then you find something that begins to open up the picture, get the bigger and bigger picture, deeper and deeper understanding, more and more bliss. It just starts unfolding, when you turn the mind within. Now you could say, well I love mystery so much, I don’t wanna know. But to me that would be pretty stupid. Because if you don’t dive within,” and by that he meant meditating, “then you remain pretty much the same, you don’t expand, you don’t grow.”

When we were taking pictures outside on the porch, I turned to him and asked him what fascinated him most about his work.

“I love seeing people come out of darkness,” he said, put his arm around me and smiled.

David’s documentary, David Wants To Fly, didn’t turn out as Mr. Lynch might have wished: the film questioned the practice, the costs people had to pay for the meditation classes and the ayurvedic medicines that were prescribed to followers, who suffered from serious illnesses. Before its release, sensing what was coming, Mr. Lynch asked that he not be included, and his foundation threatened David with a lawsuit. But David did not oblige, and when the film premiered at the Berlin Festival, no lawsuits were filed. The documentary won many prestigious awards, and sowed doubts about the meditation movement that have persisted.

Despite his belief in the health benefits of Transcendental Meditation, Mr. Lynch, a heavy smoker who did not quit until 2022, told an interviewer last year that he’d developed emphysema, could not walk even short distances without supplemental oxygen, and due to this and fears of COVID that he was housebound. Earlier this month, Deadline reported, he had to flee his Los Angeles area home due to the Sunset Fire. His children did not give a cause of death.

Regardless, Mr. Lynch loved to meditate and profoundly believed in its healing powers. On Saturday, his children called his fans to come together and celebrate their father’s love for mediation. “Let us come together, wherever we are, to honor his legacy by spreading peace and love across the world. Please take this time to meditate, reflect, and send positivity into the universe. Thank you for being part of this celebration of his life. Love, Jennifer, Austin, Riley and Lula Lynch.” His four children wrote.

One of the many Lynch quotes floating through the internet these days says, “I don’t know why people expect art to make sense when they accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense. The big mystery is life as a human being … Life is filled with mysteries, just filled. Human beings, we’re like detectives.”

The actor Kyle MacLachlan comes to mind. He played two different detectives in Mr. Lynch’s films. First in the movie “Blue Velvet,” where the college student Jeffrey Beaumont returns to his hometown after his father suffered a heart attack, and finds a severed ear in the grass in an idyllic, suburban 1950s world. Or four years later, when Mr.MacLachlan returned as the FBI agent, Mr. Dale Cooper, driving to Twin Peaks in his car to look for a killer, who murdered a girl in a small town with many secrets.

The dark-golden Hollywood lighting, the soundtracks, the slow, slow pace… Mr. Lynch’s movies are poetry in motion.

The Cut posted a tweet by Mr. Lynch from June 18, 2010:

“This weekend I’m going to try to find out if I’m connected to the moon.” Mr. Lynch wrote.

The following tweet, three days later on June 21, 2010 read, “I’m pretty sure I’m connected to the moon.”