Lucky Larkin, at His Centenary

It is good to allow men, living and dead, to be complicated. Larkin was not perfect; that is why he is our poet. Were he here, what would he tell us about himself?

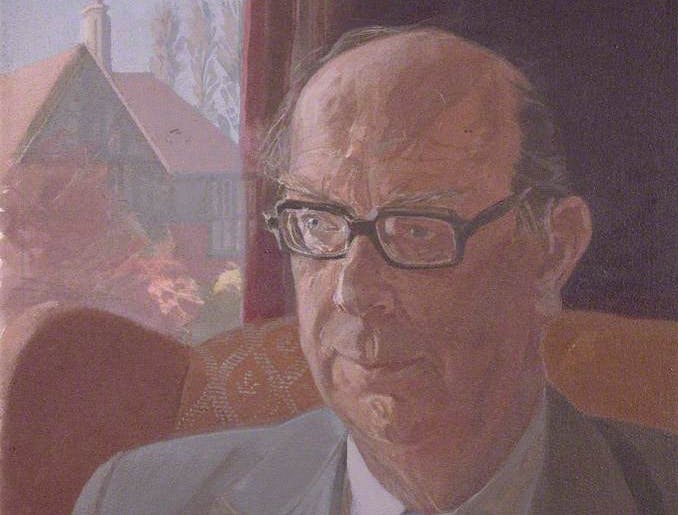

The centenary Tuesday of the birth of the late Philip Larkin invites some reflections on his gloom. “Death is no different whined at than withstood,” the poet wrote in “Aubade,” published in 1977 in the Times Literary Supplement. Looking at his pinched face — myopic and annoyed, glowering up from the cover of “The Complete Poems” — we wonder how to celebrate such a pillar of melancholy. Were he here, what would he tell us about himself?

Would he start by telling us that he was born on August 9, 1922, at Coventry, a town for which he maintained little fondness —

‘Was that,’ my friend smiled, ‘where you “have your roots”?’

No, only where my childhood was unspent

I wanted to retort, just where I started.

Would he tell us about the father enamored of T.S. Eliot and Hitler? About the stammer? Would he talk about discovering jazz?

Or would he start later — with the school prize in English and the high marks in Latin and French? With Oxford in 1940? Larkin’s eyes were too bad for army service, so he spent the war years listening to lectures from C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, whose discourses on “Beowulf” he detested. His acid comment: “I can just about stand learning the filthy lingo it’s written in. What gets me down is being expected to admire the bloody stuff.”

Let us say he would start in that ponderous, didactic baritone at Oxford, where he met Kingsley Amis — a lifelong friend and gentle parodist of the prematurely bald Larkin, who served as the basis for the titular hero of Amis’s first novel, “Lucky Jim.” Jim Dixon, a postgraduate at a red-brick university like the ones Larkin haunted as a librarian after leaving the dreaming spires, is unhappy: “All his faces were designed to express rage or loathing.”

Amis’s Jim is — unsurprisingly, given the title — lucky. He gets the girl, gets an easy job, and gets out of his university’s unnamed provincial city. Larkin’s fortunes were less sterling, beset as he was by frustration in love and work, but in 1945 he did manage to publish “The North Ship,” his first poetry collection. He was not pleased with it. “They are such complete rubbish, for the most part,” he wrote in 1965 on the occasion of their republication.

It was 10 years before he would publish a collection again. He wrote two novels to good but not exceptional reviews; he moved and worked at Belfast for five years. In 1955, he returned to England and to poetry — and what an arrival. “The Less Deceived” marked maturity, the advent of the wry speaker, the elegy of the everyday:

Why should I let the toad work

Squat on my life?

“He had perfect diction — the center, really, of his poetic gift,” the Sun’s poetry editor, Joseph Bottum, wrote to us. So he did. Larkin moves us not because he makes us happy, but because he gives us a language for speaking to ourselves about countless, unheeded daily troubles: inkblots and missed buses, coffee grounds stinking in the kitchen drain. He found the language of the gray-flannel ordinary, and wrote its national poetry.

Were Larkin here, what would he read us first? Would he intone,

Watching the shied core

Striking the basket, skidding across the floor

Shows less and less of luck, and more and more

Of failure spreading back up the arm

Earlier and earlier, the unraised hand calm,

The apple unbitten in the palm.

Or would he begin with Tory imperial disappointment —

Next year we are to bring the soldiers home

For lack of money, and it is all right.

Places they guarded, or kept orderly,

Must guard themselves, and keep themselves orderly.

We want the money for ourselves at home

Instead of working. And this is all right.

Politics, and political correctness, have haunted Larkin’s legacy in recent years. His admiration for Louis Armstrong does not balance casual racial slurs in his letters; one suspects critics’ real complaint is his admiration for Enoch Powell and Prime Minister Thatcher. Culture has suffered. In June, the British secondary exam board announced it was axing Larkin from the curriculum in favor of “more poems by contemporary and established poets of colour.”

We feared this modish hatred might depress the centennial fête, but we are heartened by what we see. The Philip Larkin Society, an unfailing champion of the poet’s work, has a full slate of celebratory activities. The New Statesman, hardly a reactionary bastion, published reflections on the poet from 10 luminaries including the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, and Julian Barnes, the acclaimed novelist.

It is good to allow men, living and dead, to be complicated. Larkin was not perfect; that is why he is our poet. And so, we like to think, were he pressed to describe his work to us, the aged poet might recite some of his best-loved lines —

Rather than words comes the thought of high windows:

The sun-comprehending glass,

And beyond it, the deep blue air, that shows

Nothing, and is nowhere, and is endless.