Kate Middleton’s Photography Scandal Is as Old as Queen Victoria, Show at the Met Explains

An arresting photography exhibit makes the case that the lens may not lie, but it can bend the truth.

‘The Real Thing: Unpacking Product Photography’

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Ave., New York

Through August 4

Tucked into a room on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s second floor is a small but mighty show called “The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography.” It comprises more than 60 works, all drawn from the Met’s own collection, a ransacking of the archives that showcases, in the words of the show’s curator, Virginia McBride, the “artistic potential of the camera to persuade and enchant.” Also, to deceive.

Whether a lens can lie is being hotly debated in the wake of the release of a photograph by the princess of Wales, Kate Middleton, that news organizations have judged to have been an altered composite. The princess took to X to explain that “like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editing. I wanted to express my apologies for any confusion.” Now, a second image, one that includes the late queen, has come under scrutiny.

“The Real Thing,” whose first work, “Articles of Glass,” by a pioneer, William Henry Fox Talbot, dates to before 1844, argues that photography, even in its infancy, was never naive. “Articles,” along with “Pitcher and Two Glasses” and “Plaster Casts of Bishops’ Miters and Papal Tiara” — all shot between 1844 and 1855 — are captivating because of their composition, their arrangement of tall and short, rounded jugs and looping handles.

If much of the Met’s gargantuan collection swears allegiance to that aesthete’s tattered banner of “art for art’s sake,” this show displays a more practical bent. Its photographs all owe their origins to what the museum calls the “commercial sector,” meaning the images were shot to help sell inventory. They were not expected to just be beautiful, but to seduce viewers out of the contents of their wallets. Many of the photographs were owned by Ford.

A particularly arresting photograph, suspended between the old and the new, comes from the Schadde brothers, who plied their trade at Minneapolis more than a century ago. “Satinettes, Filled Confections and Ye Old Style Stick Candy,” which appeared in the Brandle & Smith Co. Catalogue, is mouthwateringly colorful and vividly lickable. Color photography, though, had not been invented yet — a painter’s brush painstakingly produced the pigment.

Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell

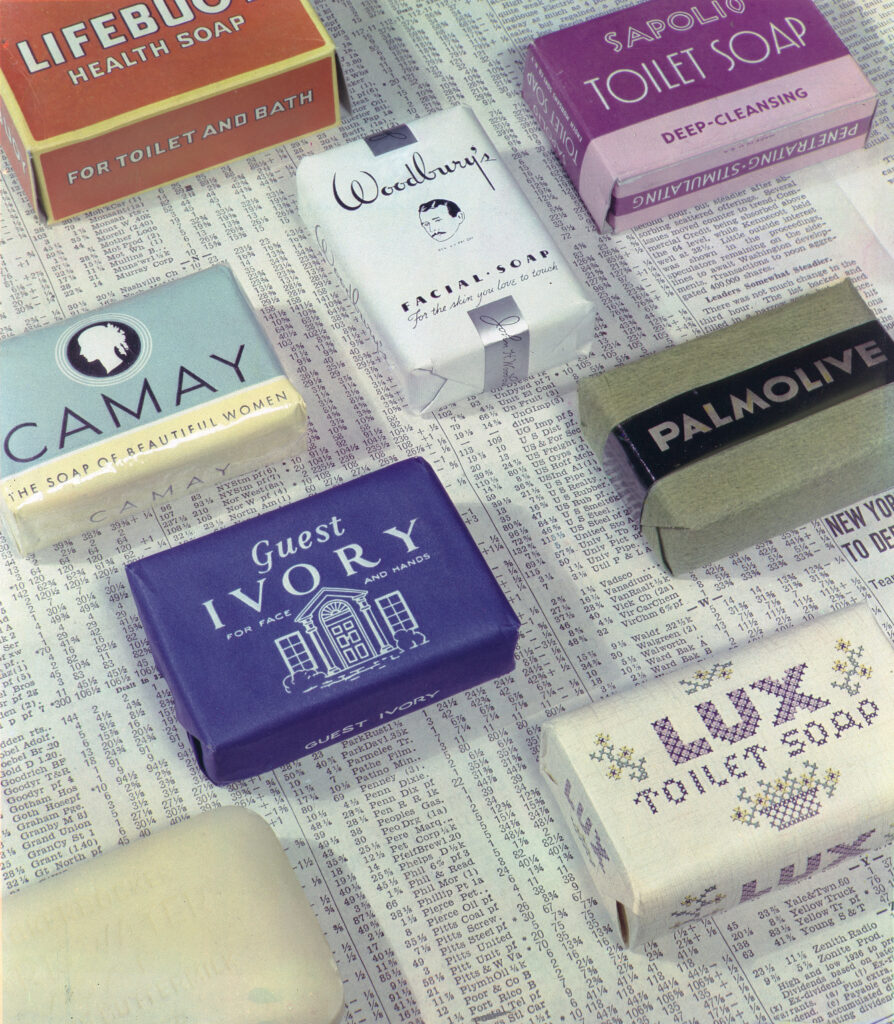

By 1936, Ralph Bartholomew Jr.’s “Soap Packaging” had no need of an artisan to illustrate it, instead relying on a tricolor printing technique. Its brilliant color stands out against Depression-era gray — the background is newsprint covered in stock prices — and Ms. McBride tells the Sun that the advertisement was likely intended to sell not the soap, but the packaging that swaddled it. It appeared in journals like Modern Packaging and Soap.

Morbidly magnificent is the “Vermont Marble Tombstone Catalogue” from the 1880’s. Salesmen would have trundled through the Green Mountain State, showing the relatives of the dearly departed these eerie renditions of monuments, bone white against deep dark backgrounds. A daguerreotype, “Man Demonstrating Patent Model for Sash Window,” shows its subject pointing, as if unfamiliar with what the new medium could be.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ford Motor Company Collection

A more avant-garde angle is announced by Stella Simon’s “Violin,” from 1930. The instrument — lean and lustrous — is propped away from the viewer, a deprivation of the expected sight line. There is something modest or coy about catching the violin from behind, as if it is not yet ready for a primetime performance. Simon would likely have been influenced by Picasso’s great guitar riffs of a decade earlier, where an instrument became a vehicle for modernism.

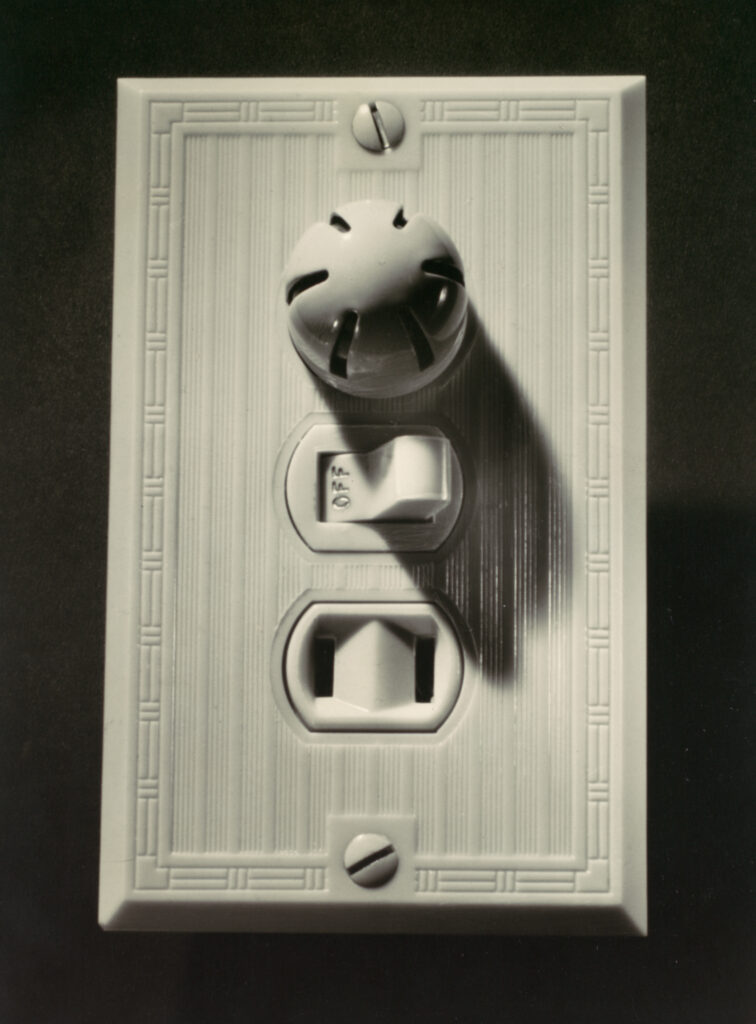

If “Violin” is a study in obliqueness, “Pass & Seymour Switch Plate,” by Fay Sturtevant Lincoln, from 1949, is a confrontation with the head-on. It begs to be flipped. Margaret Bourke-White’s “RCA Speakers,” made for a photo mural for the NBC rotunda at Rockefeller Center, pack the auditory behemoths into the photograph’s foreground. Bourke-White had just returned from a tour of the Soviet Union, and imported a sense of Stalinist scale.

A passage from the industrial to the chic leads to Irving Penn’s “Theater Accident, New York.” Appearing in Vogue, a spilled purse tells a biography in accouterments, all of which can be purchased. It is difficult to think of a more direct apprehension of Instagram influencers casually hawking wares with maniacal intent. The Met calls this image “part autopsy, part ‘I Spy.’” A black shoe, resplendently polished, appears to assume you’ll clean up the mess.

The controversy over Ms. Middleton’s photograph appears to be anticipated by a section of the show called “The Ideal User.” Take, say, “Oldsmobile F-35 With Models,” by James Doolittle. It’s from 1935, and it stages young people hanging around the car, which seems to host their conversation. It is an image of contentment, prosaic but telegraphing the contours of the good life. Few of us will be kings and queens, but all of us can appreciate a smooth ride.