It’s Raining Girls as a Pop Artist Gets Her Due

Marjorie Strider rejected the minimalism pursued by the contemporary art cool kids. Instead she went big, bright, and exuberant.

“Marjorie Strider: Girls, girls, girls,” at Galerie Gmurzynska on New York’s Upper East Side, is a blast. It is also, at least partially, a blast from the past. The solo retrospective, open until the end of this month, is a medley of work produced by the Pop Artist that spans from 1963 until her death in 2014. Strider rejected the minimalism pursued by the contemporary art cool kids. Instead, the Oklahoman went big, bright, and exuberant.

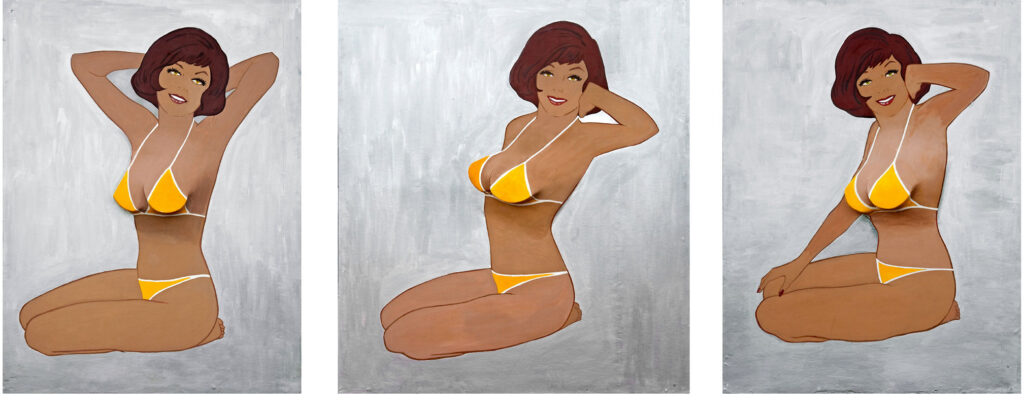

“Girls” zeroes in on a subject that parenthesized her career; the female form. An essay by Lucy Lippard from 1974 says a notable aspect of Strider’s work “is its eroticism, its need to ‘let it all hang out,’ its inelegant assertion of the flesh.” Strider’s work refuses to commit to either two or three dimensions, instead insisting on being both. The effect is something like a centaur; painting on the bottom, sculpture on top, engrossing all around.

On site at SoHo in the early 1960s, Strider was asked out by Sol LeWitt and befriended such luminaries of the contemporary as Robert Ryman, Dan Flavin, Claus Oldenberg, Judd, and Alex Katz. Two years after her first show — in 1963, at the Pace Gallery — Andy Warhol would quit painting for film. Strider was born as an artist in the age of “Campbell’s Soup Cans” and “Whaam!” To enter “Girls” is to step into a present that is, and is not, not our own.

As men’s magazines proliferated in the early 1960s and the age of the “pin up” and sexual revolution began, Strider created her “Girlie” pictures. They are described by Sid Sachs in a catalog essay as relying on “embellished caricatures” that are “pumped up and out and larger-than-life.” She described them as “a satire of men’s magazines,” but they are a strange form of satire, themselves sexy and suggestive. She can do what Hugh can do, only better.

“Triptych II, Beach Girl,” from 1963, takes the three-paneled form that adorned medieval altars and puts a bikini on it. The image is of a tan woman in a yellow two-piece in three slightly altered poses, basking in both the sun and the viewer’s gaze. Her skin is a deep tan, her lips painted red, and her eyes an otherworldly green. Her breasts protrude, making the work both more lifelike and a kind of virtual reality, simulating verisimilitude, a seduction in acrylic and foam.

“Girl With a Red Rose,” from 2014, achieves a similar effect via different means. The face and eyes echo the image from a half-century before, but this time the visage is cool, drawn in shades of black and grays. In her mouth is a three-dimensional red rose atop a bright green stem that pushes out from the painting’s surface. The chromatic difference between girl and plant haunts but also imparts pizzazz, the heat of the rose set against her cool.

Color does much of the work in “Untitled,” also from 2014. It is a closeup of a woman’s face, radically foreshortened. Her red lips are like “petals fallen apart,” as Patsy Cline sang, conveying the impression of someone gearing up for a kiss. Sunglasses on, a shock of hair, a blue- and red-striped background; she is having fun, and she wants us to join the party. This is no humorless critique or censorious scolding. It is flirtation, an invitation, and a party all at once.

One woman, captured in “Untitled,” from 2010, reclines horizontally, in a white one-piece dappled with red lips. Her body is long, her hips wide, her head tilted and propped to look the viewer directly in the eye. A wave crests overhead, but it’s hard to imagine it, or anyone, perturbing her. “Bond Girl,” from the same year, depicts a bikini-clad woman seen through a porthole, arms extended, hips jutting, ready to change your life or ruin it.

The director of the American branch of Galerie Gmurzynska, Hope Blalock, tells the Sun that she will be “doing more with Strider in the future.” A recent show at the Jewish Museum, “New York 1962-1964,” featured the artist’s work as well, suggesting a Strider renaissance. To risk blasphemy, her girls reminded this critic of the most famous girl of all, da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa.” Like hers, their tone is elusive and compelling. It’s hard to look away.