How W.E.B. DuBois Drew 50 Million Persons to an Exhibit on African Americans

‘Deconstructing Power’ — a triumph — is being remounted at the Cooper Hewitt Gallery.

The Exposition Universelle of 1900, at Paris, stretched between the esplanade of Les Invalides and the Eiffel Tower, which was new, having been built for another exposition just 11 years before. It dazzled on both sides of the Seine, yet another argument for why the City of Light would own the 20th century just as London had dominated the 19th. It was the heyday of the Belle Époque. The world was still innocent.

For some people, at least. Not for the writer W.E.B. Du Bois, charged with designing an “American Negro” exhibit as part of the American pavilion, and not for his team of students at Atlanta University, charged with creating 63 hand-drawn diagrams to tell a story of Black success 30 years after the Civil War and just four years after the Supreme Court held, in Plessy v. Ferguson, that separate could be equal.

“Deconstructing Power: W. E. B. Du Bois at the 1900 World’s Fair,” curated by Yao-Fen You, is up at the Cooper Hewitt Gallery through the end of May. At its core are 20 of what the museum calls “data visualizations” on loan from the Library of Congress. These posters do triple duty as works of art, conveyors of information, and political documents that tell to the world the story of Black Americans. The Exposition des Nègres d’Amérique was a triumph.

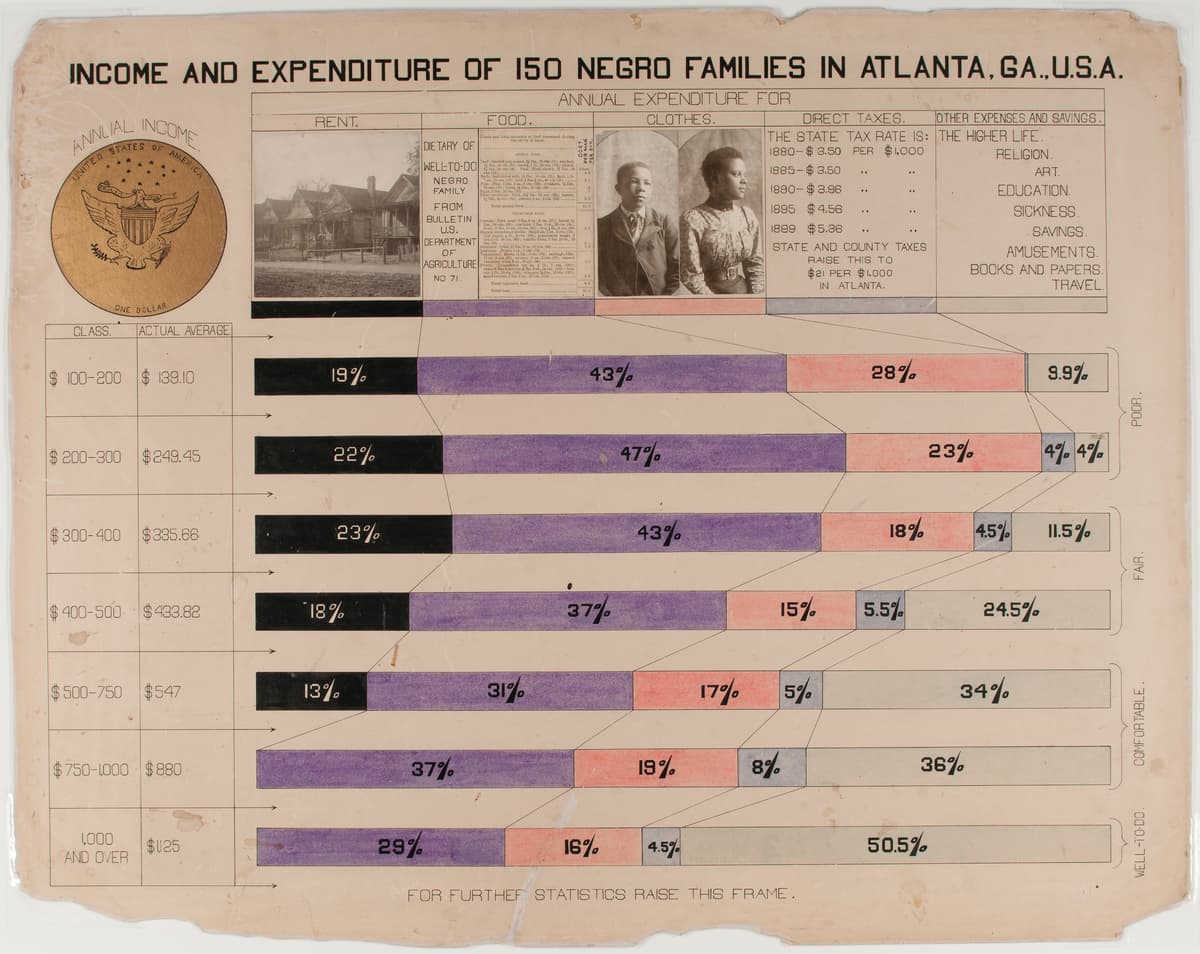

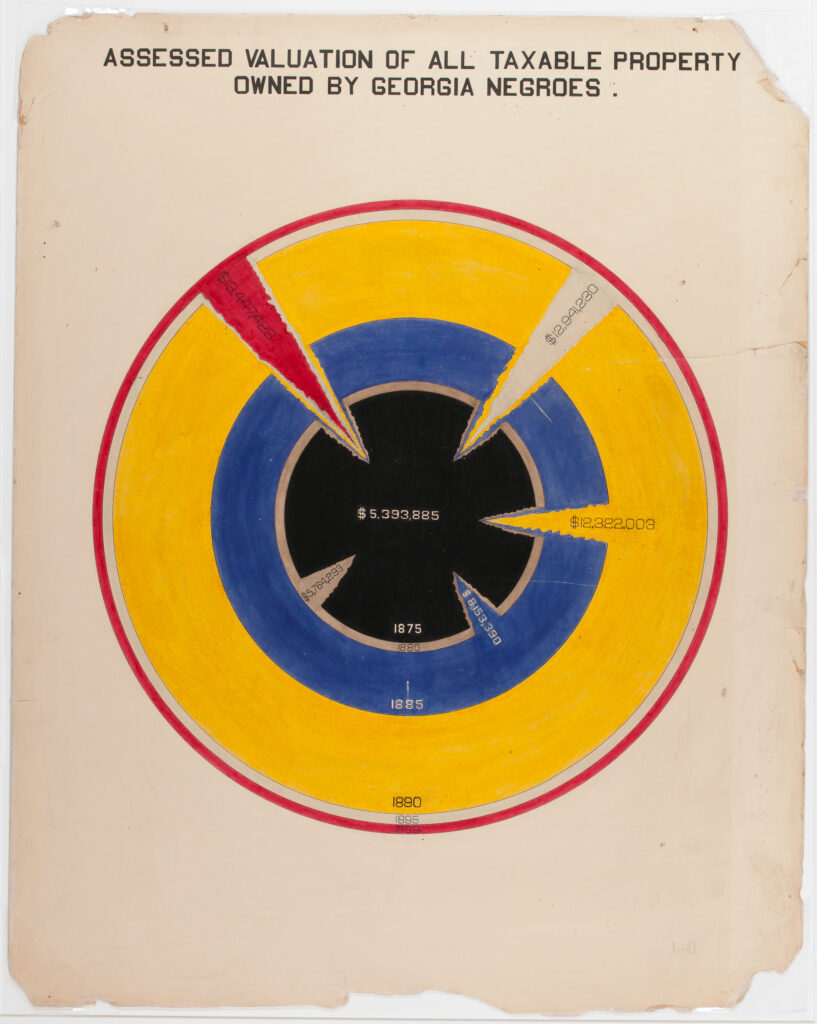

The data visualizations are hand-drawn and lettered in graphite, watercolor, and ink, with simple geometries and bold colors. They anticipate the bright abstractions of Cubism, just over the horizon. Also echoed are the work of Eli Lissitzky, who began illustrating Yiddish children’s books and became a lion of the avant-garde, all space age geometries and, eventually, Soviet propaganda.

Seen from a couple of paces back, the posters are pleasing to the eye, satisfying in the way elegant design can be; a well-designed book cover or website, the interface of your iPhone. Come closer, though, and they are rich with information that tell, in Du Bois’s words, the “development of the American Negro in a single typical state of the United States,” Georgia. One diagram traces the routes of the slave trade, the cartography of indenture.

A pie chart, in bright red, mustard yellow, and sky blue, displays the professions chosen by Atlanta University graduates. Nearly 60 percent were teachers, and almost three in ten “housewives.” The school’s goal, proudly inscribed, is to “civilize the sons of the freedmen by training their more capable members in the liberal arts.” This aspiration is in line with Du Bois’s commitment to what he popularized as the “talented tenth” of the Black population.

A pyramid, its base gray and its midriff a deep blue, tells the story of Black journalism at the turn of the 20th century; 136 weekly papers and a handful of magazines and dailies. The sense of pride in the written word is palpable just decades after Black literacy was interdicted, the learning of letters punishable by death. Another graphic shows a map of America in a quilt of colors, using pigment to tell the story of massive migration in the years after the Civil War.

In a nod to the international ambit of the Exposition, one chart, “Illiteracy of the American Negroes Compared With That of Other Nations,” uses forest green bars to place that population in relation to Hungarians, Irish, and Russians. Another depicts the spike in “Negro Teachers in Georgia Public Schools” via a vertical chain of yellow, blue and red circles, a wordless but visually arresting index of progress.

These posters were just one component of a compendium of Black life. The Library of Congress provided a bibliography of 1,400 titles by African-Americans, and 400 patents by Black inventors were cataloged for visitors in bound volumes. Those who stopped by the exhibit would have seen 500 photographs of Black life, some included in “Types of American Negroes,” an album from the camera of famed Black photographer Thomas Askew.

The same year as the Exposition, Booker T. Washington founded the National Negro Business League, a vehicle for his belief in the centrality of economic progress for Blacks. Du Bois, the first Black man to get his Ph.D. from Harvard, insisted that the movement for equality focus on education and civil rights. The two were antagonists, and the civil rights movement to come would owe much to their divergent visions.

When it came to the Exposition, though, they were collaborators. It was Washington who was instrumental in securing $15,000 from Congress to fund the display. “The Exhibit of American Negroes” won the Grand Prix, and it is reported that more than 50 million people passed through it at Paris and during its subsequent tour through America. Some of it is dated, but its mix of pride, rigor, and optimism renders it resonant.

Du Bois, of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, gets the last word. He called the show “an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves,” an account of a people “studying, examining, and thinking of their own progress and prospects.” Those who today reach for a more perfect union would do well to recall what Du Bois showed the world.