How To Pursue Happiness, According to America’s Founders

For the Founders, to be happy, to attain happiness, was the result of practicing virtue as laid out by the classical writers. In other words, the individual strove to be good, not feel good.

‘The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America’

By Jeffrey Rosen

Simon & Schuster, 368 Pages

What would George Washington or Thomas Jefferson have made of social media? The question has occurred to Jeffrey Rosen because he believes that with the advent of these new communications technologies, fostering intemperance and impatience, Americans have lost their way — though they might yet be redeemed through the back door of ebooks.

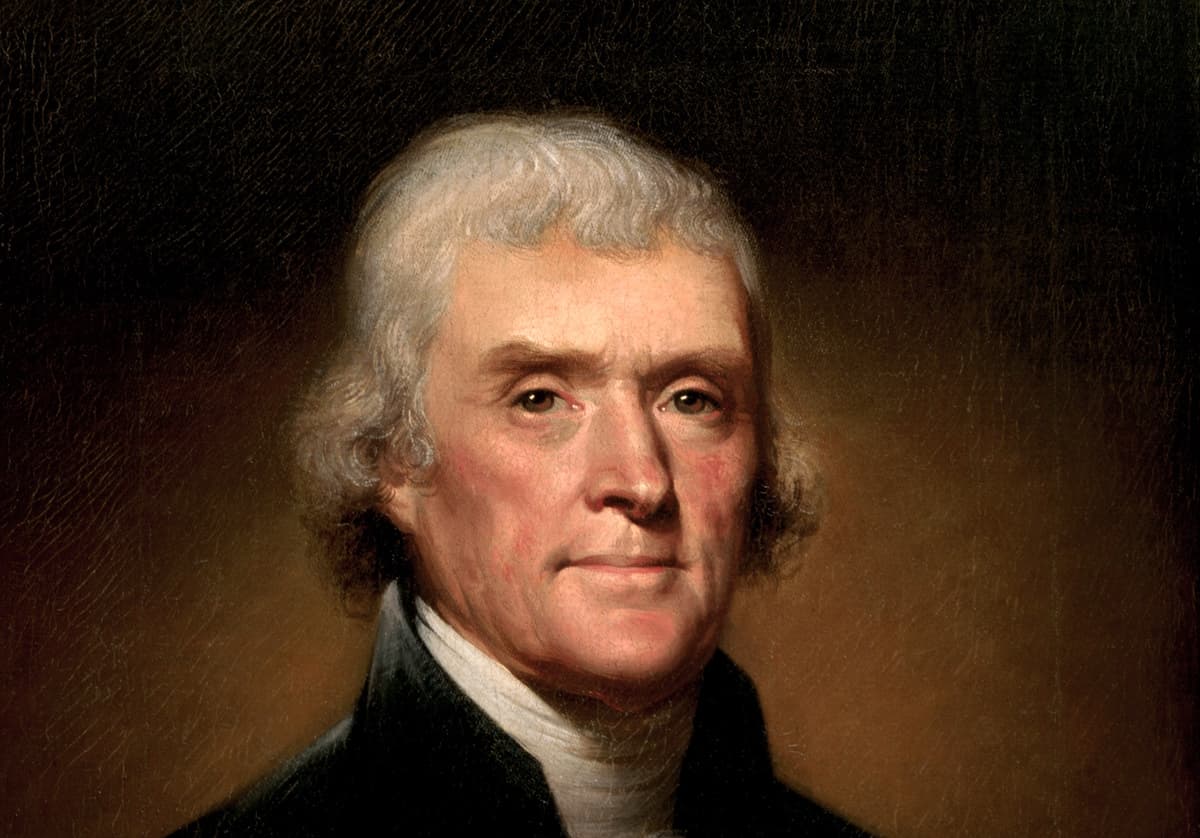

Social media, though, is hardly the main topic of “The Pursuit of Happiness.” The phrase itself, so familiar to anyone who has read the beginning of the Declaration of Independence, had a different meaning when Jefferson wrote it. To be happy, to attain happiness, was the result of practicing virtue. In other words, the individual strove to be good, not feel good.

As different as Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams were as personalities, they had a common schooling in the classical writers — especially Stoics like Seneca and Cicero, who tutored them in self-discipline and in what today we would call anger management.

Washington had a violent temper, which he gradually learned to master (mostly) by reading the ancients, who believed happiness depended on regulating the emotions. Jefferson agreed, advising the younger generation to count to 10 before speaking if one was angry, and perhaps to 100 if one was very angry.

Yet the Founders did more than pronounce such precepts. They kept detailed diaries of their reading, making sure that certain hours of every day were devoted to classical texts such as Cicero’s “Tusculan Disputations,” mentioned 37 times in Mr. Rosen’s book. Jefferson especially recommended the fourth chapter, “On the Perturbations of the Mind,” which he deemed to have the “best definition of the pursuit of happiness.”

Mr. Rosen divides his book into chapters on order, temperance, humility, industry, frugality, sincerity, resolution, moderation, tranquillity, cleanliness, justice, and silence. Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln share a chapter because they followed Emerson’s emphasis on self-reliance, educating themselves in the classic texts even as they debated with one another the cause of abolition and the citizenship of Black people.

Mr. Rosen does not present his illustrious subjects as paragons, however. He is especially pointed about Jefferson’s avarice — a cardinal failing, according to the Stoics. Jefferson indulged himself in a luxurious way of life founded on slavery even while he adjured his contemporaries not to ask others to do what you should do yourself.

Jefferson ended up in his 70s calling himself an Epicurean, who procured “tranquility of mind” by avoiding “desire & fear the two principal diseases of the mind.” So he said, though as Mr. Rosen rightly notes Jefferson had an extraordinary capacity for self-deception, forgetting or ignoring his liaison with Sally Hemings and dreading in his last days the prospect of slave revolts and a civil war.

Confronted with a vicious attack on the social media site X, Washington might well have waited to reply, as he did after his Revolutionary War soldiers gathered to complain about not getting their pay. He took his time, calmed down, and then made a show of putting on spectacles to read a speech, saying he had gone blind in the service of his country. He asked his soldiers to be patient. Many were moved to tears and complied with his counsel, eventually receiving their remuneration from Congress.

Mr. Rosen notes that if we make time for reading, as the Founders did, electronic media can supply what we are in want of. His book ends with a section describing the most cited books on happiness from the Founding Era, all available in ebooks: Cicero’s “Tusculan Disputations” and “On Duties”; Marcus Aurelius’s “Meditations”; Seneca’s “Essays”; Epictetus’s “Enchiridion”; Plutarch’s “Lives”; Xenophon’s “Memorabilia of Socrates”; Hume’s “Essays”; Montesquieu’s “The Spirit of the Laws”; Locke’s “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” and “Treatises on Government”; Adam Smith’s “The Theory of Moral Sentiments.”

Mr. Rosen notes that John Adams told his son: “You are never bored alone with a poet in your pocket.” Now, we have “access to all surviving texts published since the dawn of time—on our cell phones and tablets, wherever we are, at every moment of the day, often free of charge.”

Mr. Rollyson’s works in progress are “The Making of the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History” and “Sappho’s Fire: Kindling the Modern World.”