How Journalist Bill Cunningham, a Wartime Friend, Talked the Khmer Rouge Out of Killing Us in Cambodia

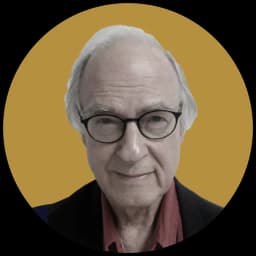

Canadian correspondent, who died in February, is remembered and applauded by his many friends at a service at Toronto.

Bill Cunningham, who died at Toronto four months ago, was among the best friends I made during the war in Vietnam. I first met Bill and his wife, Agota, a ballet dancer in her youth in Hungary, in a crowd of demonstrators in 1967 in Hong Kong at the height of Mao’s Great Cultural Revolution. He was with CBC, Canadian Broadcasting, and I was with the late, much lamented Evening Star in Washington. I owe him my life.

Please check your email.

A verification code has been sent to

Didn't get a code? Click to resend.

To continue reading, please select:

Enter your email to read for FREE

Get 1 FREE article

Join the Sun for a PENNY A DAY

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

100% ad free experience

Unlimited article and commenting access

Full annual dues ($120) billed after 60 days