Herzl, Prophet of Israel, Is Celebrated at One of the Diaspora’s Crown Jewels

The journalist did not set out to change Jewish and world history, but his achievement is so vast as to make Moses blush.

‘All About Herzl’

The Herbert & Eileen Bernard Museum at Temple Emanu-el

1 E. 65th St., Manhattan

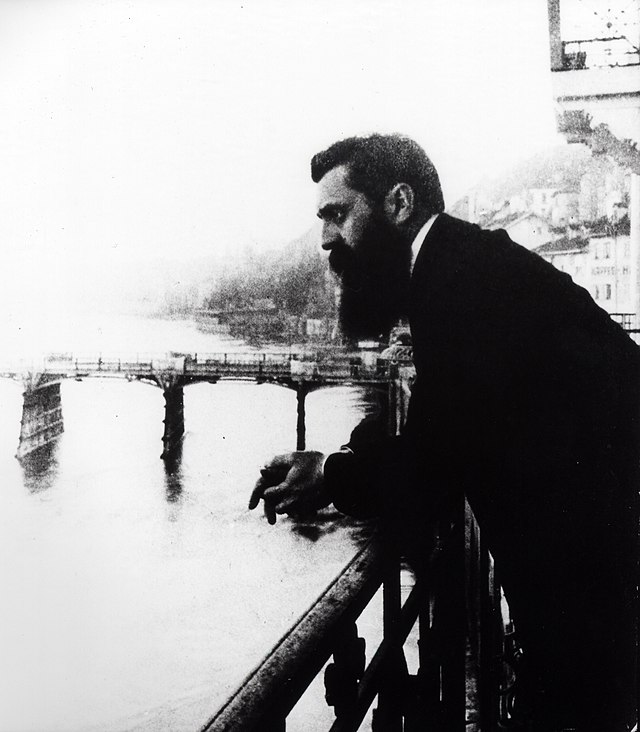

The journalist Theodor Herzl did not set out to change Jewish and world history, but his achievement is so vast as to make Moses blush. An Austro-Hungarian man of letters — an extinct species if there ever was one — Herzl went from fiddling with feuilletons and penning dispatches for the Neue Freie Presse to becoming what he is known as in Israel: “The Visionary of the State,” whose portrait hung above David Ben-Gurion as he declared independence.

How a Viennese dandy who flirted with conversion to Christianity became possessed by the necessity of the first Jewish commonwealth in the land of Israel in 2,000 years is a transformation that beggars belief. It was launched by his refusal to sugarcoat the Judenfrage, or the conundrum of how the Jews were to survive in a Europe that had found new words for old hatreds. His answer was so fantastic because the problem was so dire.

Herzl did not live to see the establishment of the state of Israel — or the Holocaust that preceded it — but his predictions have the ring of prophecy. He wrote that a “wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again. … The Jews who wish for a State will have it.” Fifty-three years later, they did. After the First Zionist Congress, he wrote in his journal, “At Basel I founded the Jewish State.” In an important sense, he had.

Via Wikimedia Commons

“All About Herzl” gives tangible and visual heft to the man and his mission. The show’s greatest debt is to a Canadian collector, David Matlow, who has with zeal assembled everything he can that is connected to Herzl. He tells the Sun that his strategy for securing the objects he desires is simple — he “pays more.” Also on display are items from the Central Zionist Archives. The only way to feel closer to Herzl would be to lay a stone at his tomb at Jerusalem.

An early report card from his early years at Pest discloses Herzl to have been a successful student. A diary, kept between 1882 and 1887 and on loan from the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, is filled with spidery handwriting, evidence of the passion for writing and language that animated the Jewish intelligentsia, just a generation or two from the ghetto, as the 19th century closed. A photograph of Herzl as a young man is shockingly beardless.

A letter to the British author — and later Zionist apostate — Israel Zangwill is written in perfect English on the letterhead of the Presse, conveying Herzl’s cosmopolitan versatility. The content, however, delivers a note of dread. Herzl tells Zangwill that he will be “very glad” to see him at Vienna, but that the city of Mozart is the “capital of Anti-Semitism.” Less than 50 years later, Adolf Hitler would announce the Anschluss from a balcony of the Hofberg.

The exhibit, curated by Warren Klein, is especially illuminating in respect of Herzl’s convening of the Zionist Congresses that were instrumental in transforming musings into a movement. Herzl’s imaginings were matched by a zeal for organization and institution-building, a combination that would be inherited by the pioneers who built the kibbutzim, labor organizations, and military cadres without which the return to Zion would have been brief.

A path not taken surfaces in a notebook from the Sixth Congress, also at Basel, where Herzl’s presentation of the “Uganda Scheme” threatened to rip apart the still-nascent movement. An open page records that 295 delegates voted in favor of sending a fact-finding group to East Africa. Originally proposed by the British colonial secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, Uganda was imagined as a temporary sanctuary in the wake of the Kishinev pogroms.

The tie to Zion — especially among the fervently faithful Jews of Eastern Europe — was too strong, and the plan was rejected. Herzl would not live to see that vote. He died, at just 44 years old, in 1904. His last words were reportedly, “Greet Palestine for me. I gave my heart’s blood for my people.” Buried at Vienna, in 1949 his coffin was loaded onto an Israeli air force jet and taken to Jerusalem. From the city’s highest hill, he overlooks the country he envisioned.