‘Godwin’ Is Almost the First Great Soccer Novel

A masters of contemporary fiction evokes the beautiful game but deserves a yellow card for kowtowing to political dogma.

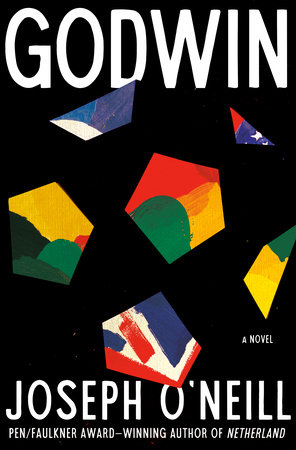

‘Godwin’

By Joseph O’Neill

Pantheon, 288 pages

Why should there not be a great soccer novel? This question has likely flickered through the minds of many writers who double as devotees of the world’s most popular sport.

There is much to write about, whether mesmerizing or mundane, if one could only turn off the match. The beautiful game, though, has yet to inspire prose equal to the feats of its greatest players or most intricate stratagems.

This is all the more puzzling given, as Joseph O’Neill writes in his new novel “Godwin,” the “mystical properties of a ball” that make soccer “a harmonious … contact with the universe, itself of course filled with spheres.” The tribalism the sport summons also seems ripe for a writer.

Few novelists are better equipped to tackle the subject than Mr. O’Neill, a subtle chronicler of globalization — and sports. In his masterpiece, “Netherland,” Mr. O’Neill managed to braid 9/11 and a passion for cricket. That book won the PEN/Faulkner Award. The critic James Wood called it “exquisitely written” and a “large fictional achievement.”

In “Godwin,” Mr. O’Neill approaches his subject from a typically oblique angle. A man named Mark Wolfe, wrestling with the “hardening and enfeebling” effects of middle age, is coaxed by his brother, a feckless soccer agent, into an odyssey to the English Midlands from Pittsburgh. Upon arrival, he learns that their purpose is to locate an African soccer prodigy named Godwin and to reap the rewards of signing him to a European club.

Despite Wolfe’s doubts, he agrees to be his brother’s emissary to an aged French soccer scout named Jean-Luc Lefebvre, who might have the secret to Godwin’s whereabouts. Arthritic and ornery, a blowhard with a thin flame of romance hovering over his grisled consciousness — Lefebvre is the triumph of the novel.

Which is not to say the novel is a triumph. From the beginning, Mr. O’Neill seems intent on contravening our expectations. Wolfe is soon discarded from the quest for the African Messi; he hears the story’s denouement months later, from the slippery Lefebvre. Meanwhile, the soccer quest is paired with an incongruous counterweight in the form of a sequence of episodes at Wolfe’s workplace, narrated by a colleague named Lakesha Williams.

This secondary drama, a power-grab among the leadership of the writing cooperative, is trivial, but this is not in itself fatal. The machinations of office life are fine grist for satire. Yet Williams’s voice is literal and allergic to irony. The clichés congeal on the page — “I thanked her from the bottom of my heart,” and, “I had always been a practical, down-to-earth person.”

There is a fantastic implausibility underlying the sections that focus on Williams. One wonders how Mr. O’Neill could make such a blunder. Williams’s story, he observes in an interview with the website LitHub, “was essential for the roundness of the book.” The writing cooperative, he elaborated in another interview, can be seen as “liberal democracy, a dream of the collective, whereas the Wolfe side [deals] with capitalism, neocolonialism.”

The answer becomes clear when, in the same interview, Mr. O’Neill evokes the “emasculation” of “a white male,” and the “calm, rational voice … of a Black woman.” The racial difference is immaterial, and centering it deserves a literary yellow card. Wolfe is rather tiresome, but not devoid of interest, despite this tendentious dichotomy. As for Williams, she is not interesting solely for being Black, any more than Lefebvre is for being French.

One critic, Ryu Spaeth, writes about this book’s conundrums in the context of contemporary political sensitivities. Weighing Mr. O’Neill’s decision not to send both Lefebvre and Wolfe to Africa, Mr. Spaeth writes: “Consider the anxiety that arises from sending two white guys to … Africa … O’Neill … is not only flirting with cliché … but has to depict a poverty-stricken nation through two characters who [don’t] understand it.”

Is this decision literary or political? In “Godwin” Mr. O’Neill hits upon a superb dramatization of the neocolonial aspects of football. To be sure, vigilance is required to avoid clichés — but such vigilance is always required, colonialism or no colonialism. Fiction is always concerned with awkwardness and partial understanding.

Half of literature, it could be said, concerns characters who don’t understand their surroundings. All that’s needed is that the author, here Mr. O’Neill, not fall into the same confusions. In Joseph Conrad’s tale “An Outpost of Progress,” two colonial officers are described as “like blind men in a large room … unable to see the general aspect of things.”

One does not require that Wolfe and Lefebvre could see the general aspect of things to wish that O’Neill had told us more about them, and Africa, and less about the Pittsburgh cooperative.