From Behind Modi’s Diplomatic Gamble in the Russia-Ukraine War India Emerges as a Player in Global Diplomacy

India ‘just wasn’t going to do this performative dance decrying the witches of Salem’ that Washington wanted.

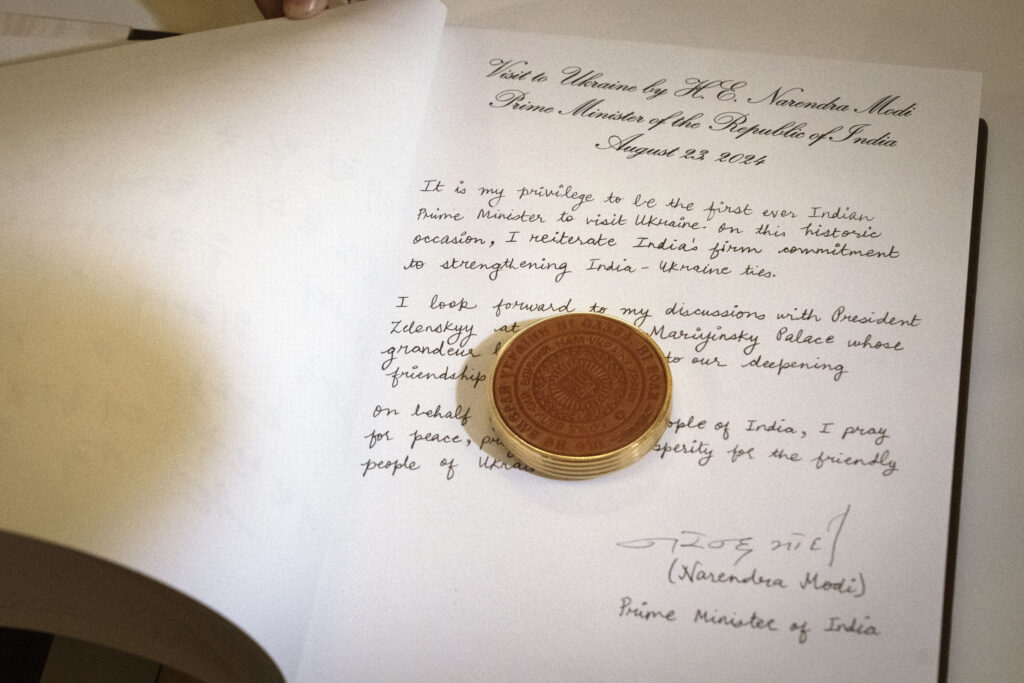

NEW DELHI — Prime Minister Modi made on Friday a historic visit to Ukraine, becoming the first Indian head of state to do so since just after the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. The visit comes just six weeks after President Zelensky expressed his “huge disappointment” over Mr. Modi’s warm embrace of his adversary, President Putin, in Moscow.

However, India’s ties with both sides of the conflict might position it uniquely to facilitate what no other government has achieved — a pathway to peace. Mr. Modi’s visit to Kyiv certainly took place at an agitated moment in the conflict, with Ukrainian forces remaining in Russia’s western Kursk region after their August 6 incursion, all while Russian troops continued to make gains in eastern Ukraine.

Yet it came at the invitation of Mr. Zelensky — and a government source in New Delhi with knowledge of the talks tells the Sun that it was with Mr. Putin’s “positive assurances.” In other words, there is clearly a growing willingness from both camps to engage in talks, but what shape those negotiations might take — if at all — is uncertain.

The source also highlighted that India does not have a policy of “neutrality” when it comes to the Ukraine-Russia war as it is often framed, but that it has been “on the side of peace since day one” and has called for a cordial solution without having to risk shattering its own diplomatic relations with Moscow.

“Both sides will have to sit together and look for ways to come out of this crisis,” Mr. Modi said after his meetings in Kyiv. Similarly, he told Mr. Putin in July that “problems cannot be resolved on the battlefield.” Mr. Modi’s visit in July to Moscow also coincided with deadly Russian strikes on one of Kyiv’s largest children’s hospitals, prompting an emotional reprimand condemning the deaths of innocent children, although he did not peg blame on his Russian counterpart.

One foreign relations expert, Rajiv Dogra, a former Indian Ambassador tells the Sun that the prime minister’s “principal objective was to repeat the message to Zelensky that he had already conveyed to Putin.”

“Mr. Modi’s advice to both was ‘this is not the era of war,’” he explains. “In both Moscow and Kyiv, he suggested that Russia and Ukraine should sit across a table and start speaking to each other. India, he added, would be happy to assist in the process, if required.”

Some Western experts are more skeptical about the extent to which MR. Modi’s government can impact serious negotiations. “India is one of the only major global players maintaining close relations with Moscow and the West. That makes India’s leaders unusually well-suited to the role of go-between if Russia and Ukraine are looking for any sort of mediated settlement,” Daniel Markey, a senior advisor for South Asia at the United States Institute of Peace, tells the Sun.

Mr. Markey cautions, though, that “India’s role should not be overstated. India can offer its good offices to facilitate Russia-Ukraine talks and could conceivably even host a ‘peace summit’ eagerly sought by Ukraine’s Zelensky, but not much more.” From Mr. Markey’s perspective, this is because India lacks experience in high-stakes international diplomacy outside its region and significant leverage over either party to the conflict.

“While Modi’s diplomatic overtures are to be welcomed,” he allowed, “they are unlikely to upend the defining dynamics of the conflict.”

Washington’s Quick Turn Around

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, India, which has long maintained defense and economic links with Russia but is also close to America and a member of the Quad, was expected by many to follow Washington’s lead. Delhi, though, never formally censured aggression nor joined the imposition of the sanctions — much to the dismay of America and the West.

Tensions then worsened when India pivoted away from the Middle East and dramatically increased its purchasing of Russia’s oil as the Western-led sanctions took effect, which was viewed as powering Moscow’s war effort. Even so, the upset from Washington dimmed quickly and quietly.

A senior fellow at the Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies at New Delhi, Abhijit Iyer-Mitra, tells the Sun that ties between India and the America were back to normal by the fall of 2022 because Washington essentially realized that India’s purchasing of Russian crude was helping to stop global gas prices from detrimentally shooting up.

“(India) just wasn’t going to do this performative dance decrying the witches of Salem that (Washington) wanted us to do. It just wasn’t going to happen, but that was good (for America),” Mr. Iyer-Mitra explained.

The China Factor

There is, in any event, more to Mr. Modi’s positioning as a potential Ukraine-Russia mediator than adulation on the world stage and preserving its energy supply. Analysts point out that India is also seeking a resolution to the Eastern European war to prevent further Western isolation of Russia, which could drive Moscow into a closer alliance with Communist China — India’s rival in Asia. India and China have long struggled with unresolved border disputes and competition for regional influence and economic dominance. Their rivalry is further fueled by strategic alliances, military expansion, and efforts to influence neighboring countries.

Despite urging India to take a firmer stand against Moscow in 2022, America and its Western allies chose not to apply firm pressure or sanctions on Delhi, understanding that the West needs India on its side to offset Communist China in the region and stand in the way of Beijing and Moscow forming even tighter bonds.

“Russia and China cannot come together. We are a third-world country, and we don’t have Western methods (of) weapons of war,” Iyer-Mitra remarked, noting that that would put India in a very precarious geopolitical position should tensions erupt. “We can’t carry out that kind of precise warfare, small numbers against a huge world kind of thing. We can’t do that.”

Indeed, the presence of two world and nuclear powers hostile to India would pose a significant threat to the America and its allies, who could well be drawn into the conflict. “So technically, through the Cold War, even though we were seen as being in the Soviet camp, we were not in the Soviet camp. We had the same objective as America: to break Russia and China apart. Our policy still remains,” Iyer-Mitra argues. “Keep Russia and China separate, and to do that, you do whatever is required — buy Russian weapons, buy Russian oil.”

Mr. Markey also reiterates that India has repeatedly argued that its national economic and security interests require an independent policy stance, one that maintains vital energy and defense ties with Russia. He says that Washington has “grudgingly and pragmatically accepted these realities.”

“Given the U.S. desire to build a strategic partnership with a strong and economically vibrant India, New Delhi’s reliance on Russia has more or less been accepted in Washington as a necessary evil,” he adds. “If it now means that Modi can help to foster a Russia-Ukraine settlement, that would be welcomed by champions of the U.S.-India relationship as an important silver lining.”