For This Correspondent, No Assignment Seemed Too Dangerous

One doesn’t have to agree with Lewis Simons’s politics to appreciate ‘To Tell the Truth’ as a highly readable, informative account of his time covering many of Asia’s greatest conflagrations.

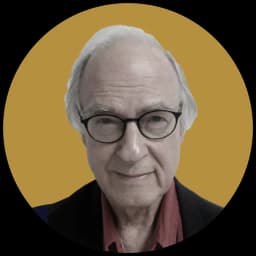

‘To Tell the Truth: My Life as a Foreign Correspondent’

By Lewis Simons, Foreword by the Dalai Lama

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 288 Pages

Correspondents, if they hang in there long enough, can lead rich and varied lives. Few have lived through more exciting and turbulent times than Lewis Simons, whose career spanned years with the Associated Press, the Washington Post, Knight-Ridder, and the San Jose Mercury News, rounded off by assignments from the National Geographic.

Mr. Simons tells it all in a book aptly titled, “To Tell the Truth,” beginning with the venality of the Philippines dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, his profligate wife, Imelda, and their billionaire cronies and friends. He and two other correspondents for the Mercury News won the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting in 1986 for exposing the widespread corruption that led the widow Corazon Aquino, whose husband, Benigno, was assassinated by Marcos henchmen, to the presidency.

That’s for starters in a book that spins through Mr. Simons’s childhood as a butcher’s son in New Jersey, his rocky record in school and college, and his grueling ordeal in basic training in the Marines. It was after he got a job as a neophyte promotion writer for ABC that a boss recommended him for Columbia University’s journalism school.

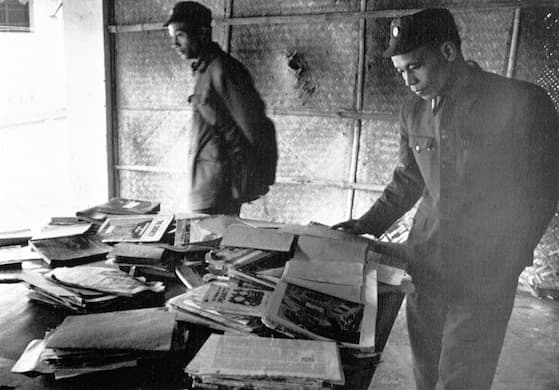

From there his record was mostly uphill, including his marriage to a j-school student, Carol, who stuck with him from one great assignment to another during which they had two daughters and a son. In first-hand accounts of suffering and death from Vietnam to Cambodia to Bangladesh, he contrasts the luxuries of wealth with the ugliness of poverty, lacing his account with bits of wit along with historical insights.

Not the least value of this book is the lesson it offers for all settings and circumstances. “Something happens somewhere and someone needs to cover it,” he writes. “Whether you know the place well or are a complete stranger, whether a colleague is waiting to help or you’re on your own, whether people are killing each other in the streets or casting ballots at the polls, like a firefighter, police officer or soldier, you go.”

Those words were the credo of a journalist to whom no assignment seemed too dangerous, difficult, or complex. Interestingly, he sees India as his favorite country even though he, Carol, and the kids came down with hepatitis, a devastating illness. “The rich grew richer, the poor remained miserable,” he writes of Indira Gandhi’s program to “eradicate poverty.” Finally, he was expelled for reporting on the Emergency proclaimed by Gandhi, leaving Carol to get out with the intervention of the American ambassador.

Mr. Simons’s writing is all the more readable for the humor he brings to the ups-and-downs of his life, from his and Carol’s trip in a broken-down car en route to his first real job with the AP in Denver to sipping a glass of foul-looking water in India just to be polite. “Periodically,” he writes, after gatherings in Japan where the guests take off shoes at the door, he “returned home in someone else’s black slippers.”

Yet Mr. Simons intermingles serious stuff with personal memories. He’s particularly critical of Secretary Kissinger for siding with Pakistan’s leaders at Islamabad in their brutal, bloody repression of East Pakistan, which emerged as Bangladesh in 1971. He castigates “the lies” told by the Americans in the daily “5 o’clock follies” at Saigon, and he blames Washington for “demonizing” the Japanese in bitter trade disputes.

He hates President Trump, America’s “arsonist in chief, ” for having “relentlessly attacked the press, in Soviet and Nazi-era rhetoric, as ‘fake news’ and ‘the enemy of the people.’”

Mr. Simons is as puzzled as anyone by what got us into Vietnam. Had Harry Truman “listened to appeals for cooperation from the anti-colonial, independence-minded revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh,” he writes, “millions of Vietnamese and tens of thousands of American lives may have been spared.”

Maybe, but then, was the discredited “domino theory” about what China might do post-Vietnam all that stupid, as he suggests? Look at China today claiming the South China Sea, threatening Taiwan, forming anti-American relationships from North Korea to Africa: What are the answers, the rights and wrongs?

It was 50 years ago this month that “North” Vietnam freed the American pilots whose planes were shot down over the North, many in the “Christmas bombing” before Mr. Kissinger negotiated the “Paris peace” that led to Hanoi’s victory in 1975. At the release of the last 67 pilots, one of them got annoyed as their captors showed us around “the Hanoi Hilton,” spruced up, clean and neat. “This is not the way it really is here,” he told me before a North Vietnamese guard ordered, “No talk, no talk.”

One doesn’t have to agree with all of Mr. Simons’s suitably liberal politics to appreciate this book as a highly readable, informative account of a period in which he covered many of Asia’s greatest conflagrations, setting examples for journalistic survival in a badly divided, bloody world.

He ends, though, with a story that has nothing to do with the news — his struggle to get a great surgeon to operate on the student monk brother of his Tibetan guide.

Mr. Simons’s “human feelings triumphed over his journalistic need to be not involved and secured treatment that saved the monk’s life,” the Dalai Lama, whom Mr. Simon interviewed four times, writes in a brief foreword. The tale of the surgery in New York’s Beth Israel Hospital climaxes this saga of a remarkable career.