Florida Book-Removal Effort Runs Up Against Warning From Samuel Alito

At Escambia County, Florida, Attorney General Ashley Moody is arguing that school libraries should ‘convey the government’s message.’

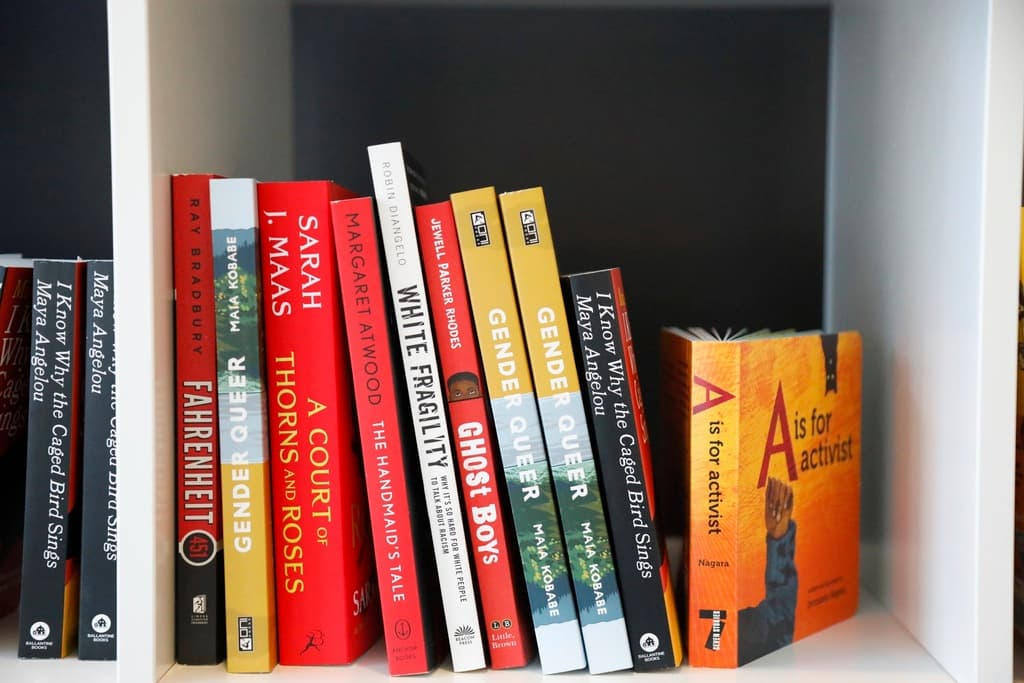

In a filing in a case concerning Florida’s removal of books it considers inappropriate from schools, the attorney general of Florida, Ashley Moody, lays out a rationale for the state’s actions, saying that school libraries exist to “convey the government’s message” — an argument that runs counter to Justice Samuel Alito’s warning about “government speech.”

Please check your email.

A verification code has been sent to

Didn't get a code? Click to resend.

To continue reading, please select:

Enter your email to read for FREE

Get 1 FREE article

Join the Sun for a PENNY A DAY

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

100% ad free experience

Unlimited article and commenting access

Full annual dues ($120) billed after 60 days