Florence Nightingale Now: A Novel Shifts Not Only the Famed Nurse’s Perspective but Our Own

The dialogue makes this novel a standout, creating out of two actual people characters who define their different places in a remote world made present.

‘Flight of the Wild Swan’

By Melissa Pritchard

Bellevue Literary Press, 416 pages

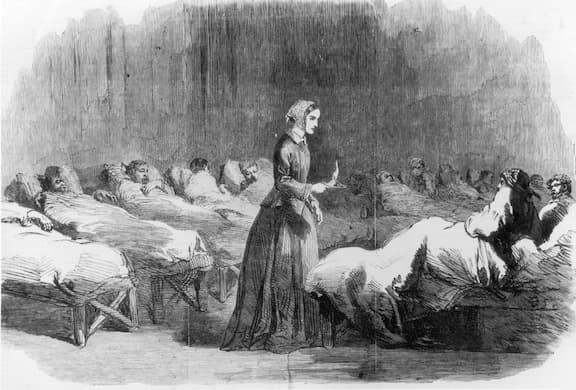

In Melissa Pritchard’s biographical novel, Florence Nightingale, the fabled “lady with the lamp” who brought women and the nursing profession to the front for the first time during the Crimean War, confronts a Jamaican woman, Mary Jane Seacole, who wants to nurse white soldiers.

Nightingale is intrigued with Seacole but has no time to train more women volunteers. Lionized in spite of disapproving army officers and a family worried about her exposure to disease, Nightingale finds Seacole, “around forty, dark-skinned and possessed of the most unusual eyes,” captivating. Nightingale recognizes a shining intelligence “and something else, something rare in this place, so rare that I’d nearly forgotten it—a natural good humor. I liked her instinctively.”

Nightingale confides to her journal that Seacole “liked me a little, too—after all, we both cared about helping soldiers, both of us were unmarried by choice (I asked), and both of us were dedicated to nursing.” Their dialogue makes this novel a standout, creating out of two actual people characters who define their different places in a remote world made present:

“Who is it you work for, Miss Nightingale?” she asked.

“For the British government. The army, specifically. Why? Whom do you work for?”

“Myself. And those soldiers who have need of me. I answer to no government.”

“I see.”

“Do you? Do you see that by working for the government you are part of a class system that oppresses the poor and keeps those like myself ”—here she pushed up one sleeve of her dress, exposing the skin of her arm—“enslaved?”

I wanted to protest, to tell her about my grandfather, his life’s work, abolishing the slave trade, but it seemed irrelevant—no, not even that, but … but what? A sign of my privilege.

Eating her dinner, she looked up at me and smiled. There was no judgment in what she had just said to me; that was what was so extraordinary. She was not condemning me. She had simply spoken the truth.

“Yes, I suppose I do see,” I said quietly. “But I am doing my best to change that system from within.”

“Through reform?” Another thing about her. Her voice. Intelligent, calm.

“Reform is slow work, but I have always believed in effecting change from within.”

“Even in a system that allows women no power?”

“I have had the advantage of family, of means. I use those.”

She put down her fork, took a drink of water. Looked at me with a warm expression, almost as if we were friends.

“We work from where God has put us, Miss Nightingale. I am poor, an outsider because of my race. Aside from the disadvantage of being a woman, you have boundless privilege.”

“Perhaps. But does not an outsider, such as yourself, perceive the problem most clearly?” Even as I spoke, I heard the falseness of my words. Her burden was heavier than mine, yet her bearing and grace far greater. She would say one more thing that would nag at me. Shift my perspective.

“So long as men are born, generations of war hunger—war itself—will be with us.”

“I hope not, Mrs. Seacole. Truly, I hope not.”

The scene is a rebuke to Nightingale but also a revelation of her exquisite sensitivity to the implications of her way of doing good. Up to this point she has been viewed as a force of nature overturning Victorian conceptions of a woman’s place in the world. With Seacole, the novel’s frame of reference scales up, shifting not only Nightingale’s perspective but our own.

Where does such a scene come from? Look to the novel’s dedication to Ms. Pritchard’s husband, Dr. Philip Thomas Schley, who “read every draft with your surgeon’s eye for detail and historian’s attention to accuracy,” and to the acknowledgments: “To my grandmother Augusta Duwe Brown, R.N., and my great-aunt, Lorna Duwe Brown, R.N., sisters and nurses. To my grandfather Dr. Clarence J. Brown, surgeon and vice admiral, United States Navy, for organizing the overwhelming task of caring for all D-day casualties, transported by boat and train to the Royal Victoria Military Hospital in Southampton, England, a grand-looking, Italianate, nineteenth-century hospital Florence Nightingale once declared a catastrophe of inefficiency.”

This novel has been generations in the making.

Mr. Rollyson is the editor of “British Biography: A Reader.”