Elephants, Gods, and Kings of India Claim a Corner of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Treasure trove from the subcontinent marks a major moment, as the Mughals take Manhattan.

‘Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting’

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY

Through June 9, 2024

The 122 paintings comprising ‘Indian Skies’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art offer witness that in the centuries that masters like Michelangelo, Vermeer, and Velázquez were working in Europe, hands of similar skill were drafting on the subcontinent. Here is summoned a world of monkeys and men, divinities and elephants, war and play. Most of all, the show, in luminous detail, suggests the polytheistic poise of a civilization older than history.

‘Indian Skies’ is drawn from the collection of Howard Hodgkins, an English painter who lent 84 of the works featured here. They are sourced from the Mughal, Deccani, Rajput, and Pahari courts between the 16th and the 19th centuries. They span, as the consul general of India at New York, Binaya Pradhan, noted at a press preview, from the “Himalayas to Rajasthan to southern India.” The showstoppers, across time and space, are the pachyderms.

The elephants are painted with the nuances that Europeans applied to ladies and landscapes. “Playful Elephant Bathing in Dust,” in watercolor and charcoal on paper, is a stirring invocation of the ludic. Its subject is twisted and silly, trunk curled, happy and alive in its body. The drawing appears to be laughing off the wall. A different season of the soul is captured in “Enraged Elephant During Training,” rendered with taut and bridled brutality.

Restraint gives way to rush in “Elephant at a Gallop,” where a slick black beast busily trots, its hooves barely hitting the ground despite the two riders perched on its sloped back. “Young Elephant Eating” is a quieter study, almost naturalistic. It radiates an intimacy with the animal and is driven by a sense of soul that exists apart from human use. The soft bend in its subject’s knees and its nubile trunk suggest a juvenile moment. There is tenderness here, and potential.

A wilder vision animates “Vishnu Liberating the Elephant Gajandra.” Here the god and the animal meet at eye level. Their interaction is charged and meaningful. It is an engagement of consequence. The elephant’s arc telegraphs that it knows enough of freedom to crave it. The pachyderm dwarfs the god, adding a poignant inversion of scale. Vines writhe around the elephant’s legs, suggesting the stickiness underfoot with which salvation contends.

Howard Hodgkin Collection, via Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Krishna Dances on the Head of Kaliya,” rendered in delicate detail, shows the deity — an incarnation of Vishnu, and sometimes thought of as the Supreme God in his own right — pummeling a serpent king with choreography. He plays the lute, as if to accompany his own dance. The serpent is charismatically long and dark, unspooling beneath the water. One gets the sense of an enchanted landscape, of multitudes and magic.

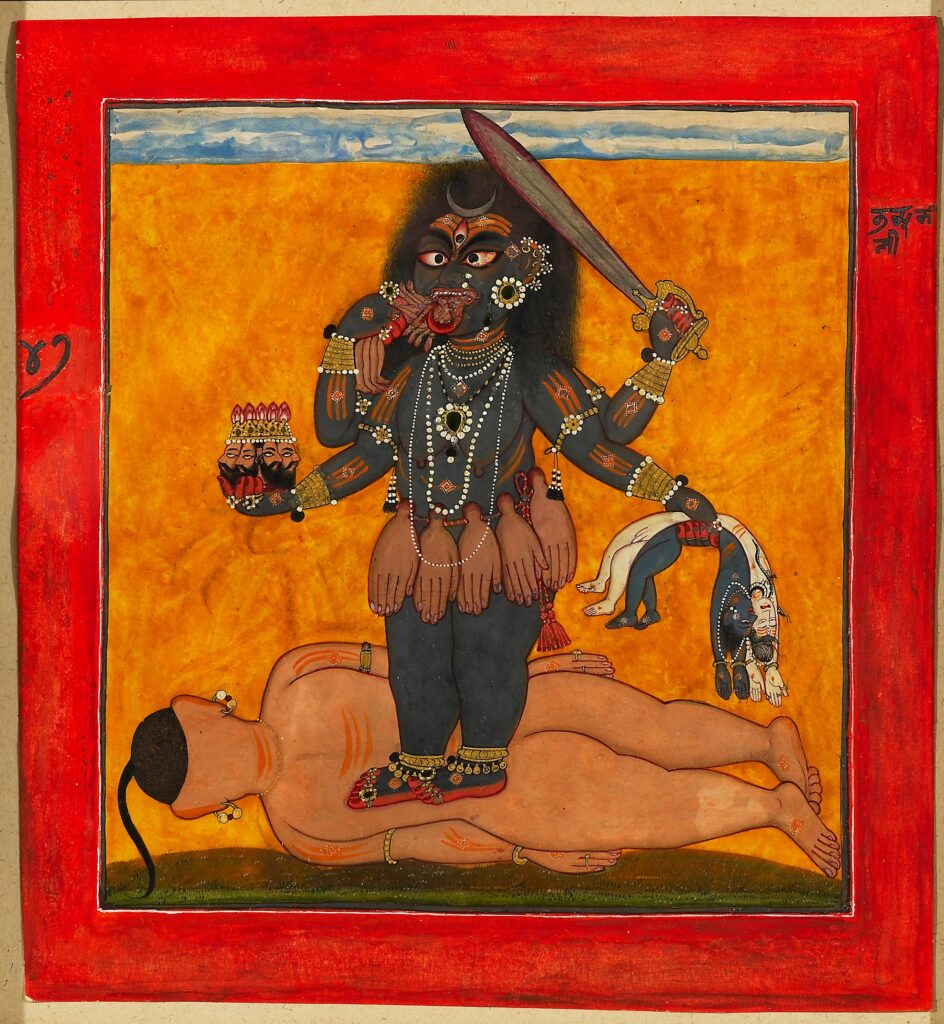

Our species is well represented, too. “A Lady Singing” is a personage with whom it is worth lingering. She is a Rajashanti “Mona Lisa” in profile. Her beauty is archetypical, open to possibility but alive to artifice. She smiles at you, but not only you. “A Court Beauty” arrests and readies to ravish, its subject stretched and beguiling. Darker is “Bhadrakali, Destroyer of the Universe,” whose raised sword promises cataclysm and serpentine arms cradle corpses.

“Harihara Sadashiva” is an astonishing composition in watercolor and ink. It summons in one seated personage a hybrid of the gods Shiva and Vishnu, a syncretic icon with five heads, 10 arms, and a potbelly. A garland of leaves hints at hallucinogenics, and dreadlocks hang past the navel. He wears a leopard skin cloth — this a divinity of the outback. The vividness of the face and physique, though, suggest, almost scandalously, a human model.

A valedictory note is sounded by “The Emperor Bahadur Shah,” from the middle of the 19th century. He was the 20th and last Mughal emperor, his domain shrunken to the walls of Old Delhi. He threw his lot in with the failed Indian Rebellion of 1857, which sought to shake the yoke of the British East India Company. In short order Queen Victoria was empress of India. The portrait is elegiac, almost vanished. It marks the end of a world.