Egon Schiele, Vienna’s Painter of Bodies Beautiful and Grotesque, Takes His Turn in the Spotlight on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue

A new show at the Neue Galerie highlights how the painter treated landscapes — yet one can’t help but be drawn to his portraits.

‘Egon Schiele: Living Landscapes’

Neue Galerie New York, 1048 Fifth Ave.

Through January 13

Austrian painter Egon Schiele’s most famous landscapes are the bodies he painted. They are spidery, elongated, twisting, and given to surprising dips and valleys. Schiele’s signatures are his hands, appendages that few have rendered with greater gorgeous grotesqueness. The painter’s people are Vienna’s fin de siècle embodied, high-strung at the carnival. They are hot and troubled like chicken can be sweet and sour or life can be sick and sublime.

“Egon Schiele: Living Landscapes” makes the case that Schiele without his portraits was still Schiele. It is a strategy the Neue Galerie has pursued before, in respect of the painter’s mentor, Gustav Klimt. His “Woman in Gold” is the jewel of Neue’s collection, but “Klimt’s Landscapes” was all green gardens, grass stains, and sunburns. The gallery pursues a similar gambit — presenting a master sideways — here. Schiele still shines.

Schiele’s life was as short as his work was intense. He was born in Lower Austria in 1890 to a stationmaster of the state railway, who would die of syphilis when Egon was 14. By 1906 he was the youngest student at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. He soon found his own style that was by turns transgressive, tender, pornographic, and even mystical. He served in World War I as a clerk, but died of the Spanish flu in 1918.

Schiele didn’t live to see the Anschluss, but his works were a favorite of Jewish collectors, and their afterlives have played out in restitution cases, as their former owners were sent to places like Dachau and Auschwitz. One work, “Portrait of Wally,” was, while on tour at the Museum of Modern Art, seized by District Attorney Robert Morgenthau. The Leopold Museum at Vienna paid $19 million to the heirs of the painting’s original owner.

The Leopold, on the Ringstrasse, holds more than 200 works by Schiele, but “Living Landscapes” has more than enough gems to justify a visit to Fifth Avenue — and a slice of Sachertorte for the road. Not everyone will be convinced that Schiele was an Expressionist Shohei Ohtani, equally adept in the distinct disciplines of landscape and portraiture. Grading on a curve, though, seems appropriate given that he was granted so little time.

The show’s first room, “My Beginnings,” gives little indication of where Schiele’s style would land. “Drying Laundry” and “Summer Night” are pleasant enough, but have something of the generic amiability of postcards. An exception is “Sunflower I,” whose droopy decay discloses an eye for rot. The second room, “My Transformations,” spotlights a step forward. “Procession” stars three women who might be Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters.

The women blend into the stony background, their faces nearly floating. Walter Pater said that the “Mona Lisa” was “older than the rocks among which she sits,” and these figures likewise appear more ancient than their cavernous cocoons. They watch, but appear to bring no good news. “Portrait of the Painter Karl Zakovsek” is the inverse. The artist is painted against a blank background against which individual hair follicles are so distinct they appear to vibrate.

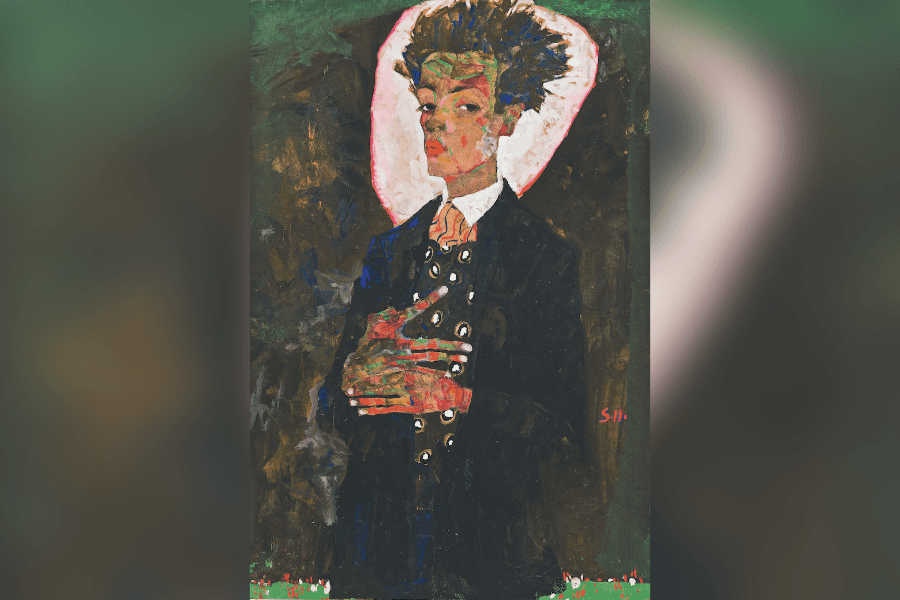

“Man and Woman I (Lovers I)” is a stunning work. Its central figures appear like sculptures of stone come to life, golems of granite engaged in lovemaking that could shake the earth. A more elegant vision is offered in “Self-Portrait in Peacock Waistcoat, Standing,” where the artist appears to vacillate between self-possession and diffidence. Schiele’s fingers seem to be everywhere at once, his hair made wild by an electric current.

“Yellow Town” features boxy houses arranged in a jigsaw-like pattern, with higgly-piggly doors and windows to convey both privacy and opacity — gossip here would happen at an angle. “Town Among Greenery” is painted from a more distant vantage point, and has about it something of the miniaturization of medieval maps. “The Bridge” and “Sawmill” deliver an industrial melancholy, the gray of city outskirts.

A darker vision is offered in “City on the Blue River I.” Black crayon imparts a sense of doom. It would be difficult to find one’s way through this town — one can imagine it swallowing an unsuspecting visitor. His model was the rural town of Krumau, where his family had roots. Schiele said: “In Vienna there are shadows. The city is black and everything is done by recipe.” In the Habsburg heartland, he found his roots amid the rot.