‘Edward Hopper’s New York,’ Up at the Whitney, Is a Portal to Another Era

The twilight zones of the painter’s imagination turn out to be both straightforward and alluringly abstract.

Visiting “Edward Hopper’s New York” at the Whitney Museum of American Art is an exercise in time travel. You know a Hopper when you see it. His stark canvases are portals into another era, and another New York. They’ll make you nostalgic for the place where you live.

The show is organized by the Whitney’s curator of drawings and prints, Kim Conaty, along with a senior curatorial assistant, Melinda Lang. On view until the fifth of March, it unfolds across a series of high-ceilinged rooms on the museum’s cavernous fifth floor, a distinctly celestial setting for a painter often figured as a laureate of despair.

Hopper was born in 1884 on the banks of the Hudson River at Nyack, at that time a hub of the yacht-building trade. His family encouraged his art, and he showed a precocity that brought him to the New York School of Art and Design, where he read Ralph Waldo Emerson and studied Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas. He loved Rembrandt, while claiming to ignore Pablo Picasso.

In his early 20s, Hopper went to work for an advertising agency, where he illustrated the covers of trade magazines. “Hopper’s New York” has a rich selection of this early work, which is jazzy and eye-catching, though Hopper hated the commercial imperative. Untouched by avant-garde currents from the Continent, he began to work in etchings and illustration.

His breakthrough came with marriage to another artist, Josephine Nivison. It was in his early 40s that the art machers at the Whitney and the Metropolitan Museum of Art began to pay heed to his canvases. Hopper was never garrulous when it came to making the case for his own work. He was wont to dismiss inquiries by saying “the whole answer is there on the canvas.”

“Hopper’s New York” is full of invitations to linger in the twilight zones of Hopper’s imagination, which manages to be both straightforward and alluringly abstract. His style is a halfway house between photographic realism and moody urban abstraction. It is not art that demands a specialist, but it is special art, intimate in the fashion that impersonal beauty can be.

The show begins with a canvas from 1946, “Approaching a City.” The painting opens from the window of an above-ground train at 96th and Park Avenue, rumbling toward Grand Central Terminal. Yet the painting is generic. It is a meditation on a city, not the city. Hopper would later reflect on “a certain fear and anxiety and a great visual interest in the things that one sees coming into a great city.”

Across his long life, as it turns out, Hopper was nothing if not a fixture of the urban landscape he painted to such great effect. For 54 years he lived and painted on the fourth floor of 3 Washington Square North. He waged long and grueling battles to fight off Greenwich Village’s sundry transformations, a master who was never a radical and a genius with no interest in bohemianism.

Another bird’s eye view of the city is offered in “New York Pavements,” from 1924 and 1925, where a cropped view of a woman pushing a stroller seen from the “El” train — to soon be replaced by the subway — suggests that in the city a key component of the scene is to be seen. “The El Station,” from 1908, is a sunnier vision of a train in the air, a different manner of altitude for the era before skyscrapers.

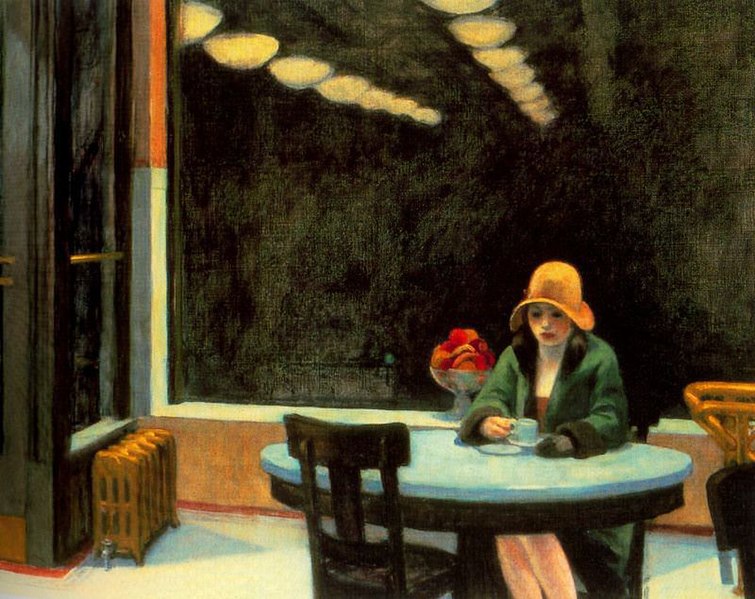

One of Hopper’s strengths is that refusal to be seduced by verticality. His gaze remained resolutely horizontal, his brush seeking out the axis where life is lived, even if viewed from a hovering slant. One masterpiece, “Automat,” from 1927, manages a kind of generous voyeurism. A young woman — female suffrage was just eight years old — sits alone at the late-night self-service establishment. The Hoppers were known to frequent automats.

More upscale is “New York Restaurant,” from 1927. The plush premises are delivered tableside, a kind of GoPro capturing the choreography of lunch service. The painter could be another diner, a waiter, or even the maître d’, surveying his dominion with a mix of wariness made of equal parts pride and anxiety. Hopper described the painting as an “attempt to make visual the crowded glamor of a New York restaurant.”

“Night Windows,” from 1928, is another view from the El train. Rectangular windows offer sightlines into a brightly lit room, while an undulating curtain creates the impression of a breeze blowing through the painting. At the center is a woman wearing a pink night slip bending over, a fleeting eroticism — more candid than planned — implicating the viewer, and painter, in casual complicity.

A later work, from 1944, is “Morning in a City.” This painting also features a woman at home, but here the view from inside rather than outside her apartment. She stands naked next to a small bed, her skin alabaster and her hair a burning red. Here it is not the painter but the subject who gazes out the window, a melancholy dreamer whose desires start in the body and end at the furthest horizon. New York has always been partial to that sort.