Dublin Goes Gaga for Warhol

A show at the Hugh Lane Gallery demonstrates that the Pop artist’s 15 minutes of fame are far from up.

‘Andy Warhol Three Times Out’

Hugh Lane Gallery

Parnell Street, Dublin, Ireland

Through January 28

DUBLIN — Seeing a work by the artist Andy Warhol on foreign shores is a little like stumbling on a McDonald’s abroad — they both engender a flash of recognition paired with the slightest cringe. The Big Mac and the Pop artist are both avatars of an American culture gone global. If one finds herself in Ireland and hankering for a Caravaggio, the National Gallery awaits. The patron saint of the present, though, is elsewhere.

“Andy Warhol Three Times Out,” at Dublin’s Hugh Lane Gallery — Ireland’s premiere modern art museum — is worth foregoing a pint of Guinness, at least for an hour or so. It’s been in the works for a half decade. It gathers more than 250 works by the son of Slovakian immigrants who became the most influential artist of the second half of the 20th century. This show delivers the fan favorites, but also opens new avenues into Warhol’s visual hegemony.

Warhol’s iconic images are borrowed — some say stolen — and filtered, as if he anticipated Instagram by decades. The show doesn’t skimp on the “Campbell Soup” cans and “Marilyn Monroe,” works that once scandalized and now feel inevitable. Warhol — his given name was Andrew Warholia Jr. — began, though, not as the magus of consumer culture but as a commercial illustrator. That is where “Three Times Out” begins.

It is a good place to start, because it conveys a sense of Warhol’s talent when it was still young and on the make. These drawings flirt and wink, as if Madison Avenue let down its hair. Warhol moved merchandise, but there was also a surplus — he was an art man rather than an ad man. There is something about these renderings of the Renaissance preparatory sketch, only without the ensuing paintings. Camp was coming.

“Flowers,” which is based on a magazine image of hibiscus blossoms, is particularly arresting, visions of acid-washed flora that Warhol grew in the hothouse of his own silkscreen method. They nod to the venerable centuries of still lifes and landscape paintings — squint and there is Cezanne — but they are more strongly harbingers of a graphic and digital age, emojis on a drop-down menu, hallucinogenic hack work.

More chilling is a series Warhol called his “death pictures,” highlighted by a handful of studies, “Electric Chair,” that riff on a photograph of the instrument at Sing Sing Prison where Julius and Ethel Rosenberg met their fate. The death chamber is empty, though, and a sign over the door reads “Silence.” Yellow, pink, and green versions each propose different genres of haunting, like strobe lights at a disco of death.

©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Via Hugh Lane Gallery

A room full of “Screen Tests” turns attention to Warhol’s camera work. Here are the faces of the painter Salvador Dalí, the singer Bob Dylan, and aged avant-gardist Marcel Duchamp. The lens, though, is particularly attuned to some of the women Warhol called his “superstars.” Ann Buchanan, with reams of brunette locks, squints back tears. The most favored — and abused — of them all, Edie Sedgwick, is breathtaking, ever young more than half a century later.

Warhol’s self-portraits show that he subjected himself to much the same treatment that he imposed on his subjects. They are indelible, even intrusive, while also fugitive and fragmented. One, from 1986 and rendered in purple and black, borrows the aesthetic of an X-ray machine to capture a vision of Warhol that is decidedly unhuman, even cyborgian. The image is poised at the place where self-absorption meets self-dissolution.

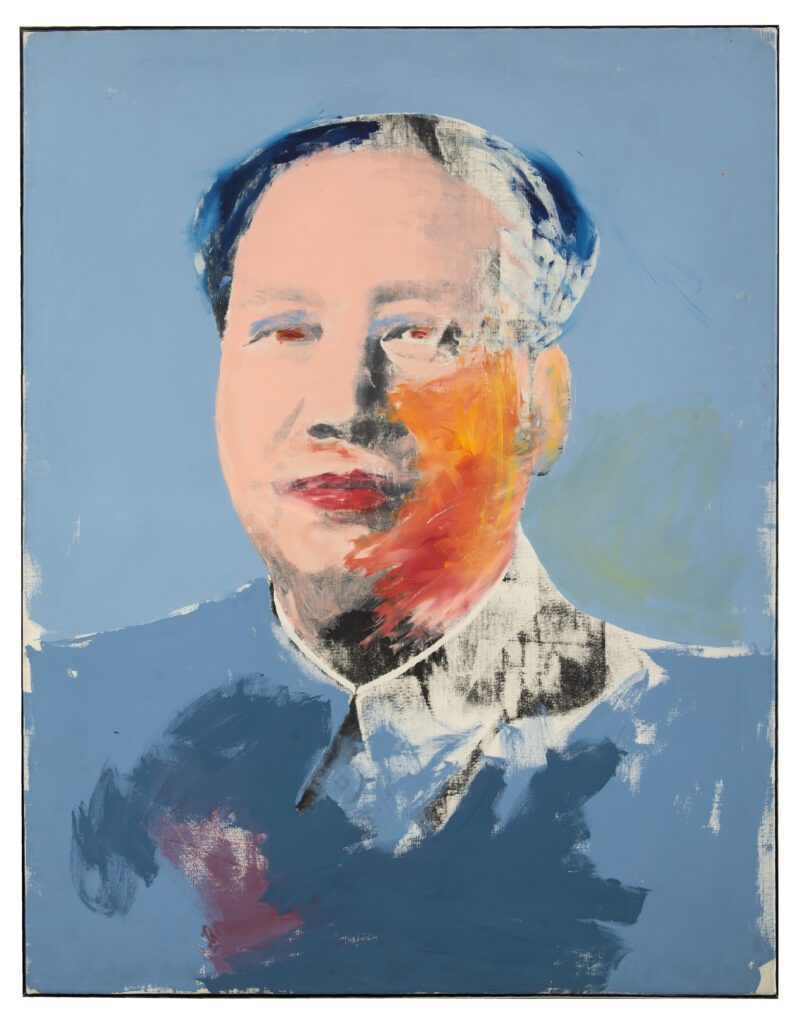

“Three Times Out” positions Warhol as an artist of his era, which was entirely encompassed by the Cold War. The “Hammer and Sickle” silkscreens depict actual tools in a kind of proletariat still life. The “Mao” series, images of President Nixon that Warhol created for the campaign of George McGovern, and a striking Jackie Kennedy sequence resurrect a bygone pantheon. “Dollar Sign,” from 1981, heralds boom times ahead.

The show, well curated by Barbara Dawson and Michael Dempsey, links Warhol with another modern master, Francis Bacon, born at Dublin to English parents. The Hugh Lane has the painter’s entire studio, relocated from London. It is a riot of brushes and paint, the birthing place of Bacon’s savage and swirling art. “Kneeling Figure -Back View” is placed next to a skull that Warhol rendered in much the same palette. Memento mori, or memento Andy.