‘Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy’ Dispels the Myths of Camelot

A ‘Kennedy worshiping’ kid who grew up to work at the JFK Library before evolving into a Reagan conservative looks at a president whose assassination has denied him a clear-eyed assessment.

‘Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy’

By Stephen Knott

University Press of Kansas, 280 pages

To Reagan conservative from “Kennedy worshiper” with a job at the JFK Library along the way; what a long, strange trip it has been for Stephen Knott. Now, in “Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy,” readers can walk it with him for some overdue picking at an American hero’s feet of clay.

Mr. Knott’s book isn’t a portrait of Kennedy as a saint like the one that hung in his boyhood bedroom. Readers won’t feel that he drank the Kool-Aid during his time at the library and on the 1976 Senate campaign of the slain president’s brother, Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy.

Good historians live by the Socratic maxim that “the unexamined life is not worth living,” and keep their thumbs off the scales of judgment. Mr. Knott doesn’t shy away from Kennedy’s flaws — “a serial adulterer,” he called him twice in our interview on the History Author Show — or the falsehoods concealing that he was “one of our most sickly presidents.”

The Kennedy who emerges in Mr. Knott’s telling is one with all the texture and human complexity that he has been denied since, upon his death at the hands of Lee Harvey Oswald, it was declared that, like Secretary of War Edwin Stanton said of President Lincoln, “Now he belongs to the ages.”

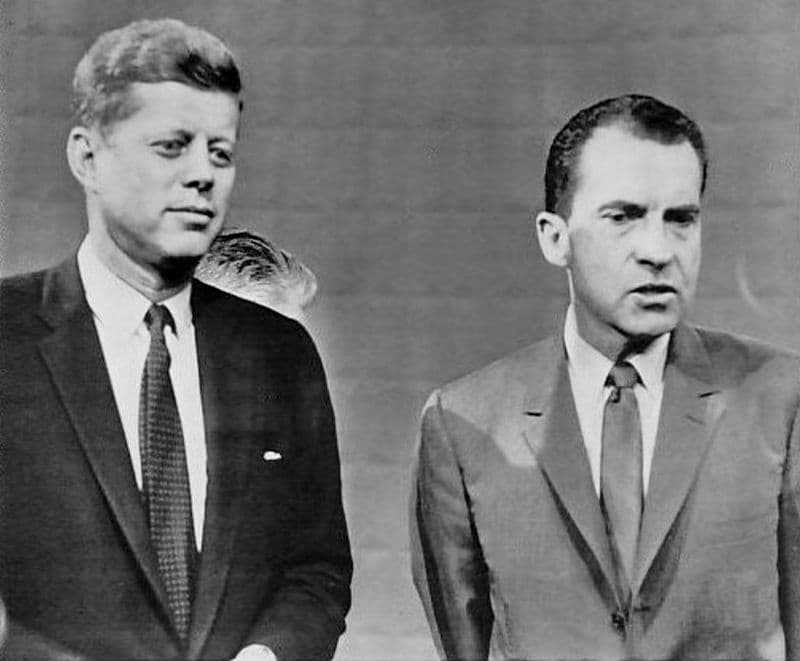

The Kennedy we meet in these pages is a charismatic master of television and a maestro of the press conference who uses those talents to build an “imperial presidency,” which the author sees as “a kind of distortion of what the American system is about” and “Kennedy’s worst legacy.”

To prevent detractors from slipping Kennedy posthumous kryptonite, his family and friends created the myth of “Camelot” after his assassination, something that grated on Mr. Knott during his tenure at the JFK Library and motivated his “first break” with the president’s hagiographers.

“They would allow sympathetic historians,” Mr. Knott discloses, “people like Arthur Schlesinger Jr., Doris Kearns Goodwin, and others, access to materials that a lot of other historians were denied.” Although he still “worshiped” Kennedy, as a “devotee of history” he felt that kind of “manipulation of the facts, manipulation of historic documents was just not healthy.”

In a world where self-promotion is the norm rather than the exception to such an extent that even Narcissus might urge us to stop chasing the spotlight, Mr. Knott’s sparing appearances on the page only when warranted is noteworthy. In the “first draft of this book,” he notes, “I actually didn’t insert myself at all.”

Mr. Knott never met President Kennedy but says he “influenced my life in many ways, and my editor and a few friends convinced me to finally insert myself, and I do think it made for a better book,” one written with a safe-cracker’s light touch.

The Camelot mythos has done a disservice to Kennedy and to America. Take the “Trollope Ploy,” which cast him as defusing the Cuban Missile Crisis by answering a conciliatory letter from the Kremlin while ignoring a more belligerent one.

This tale, refuted by declassified Oval Office recordings, set an impossible standard of anti-communist policy that inspired President Lyndon Johnson’s intractability in Vietnam, a rigidity that could have been reinforced by ignorance that his predecessor had traded NATO missiles in Turkey for the Soviet ones in Cuba.

By debunking positive myths, Mr. Knott has credibility when he goes after those on the right who cast Kennedy as just “good teeth and a full head of hair,” or the falsehood that his bold statement at the Berlin Wall, “Ich bin ein Berliner,” translates to, “I am a jelly donut.”

One knight remarks “It’s only a model” when King Arthur’s men are gushing over Camelot in “Monty Python and the Holy Grail.” In “Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy,” the fake façade of the American Camelot crumbles at last, allowing the real man to emerge from history’s rubble and stand before readers, warts and all.