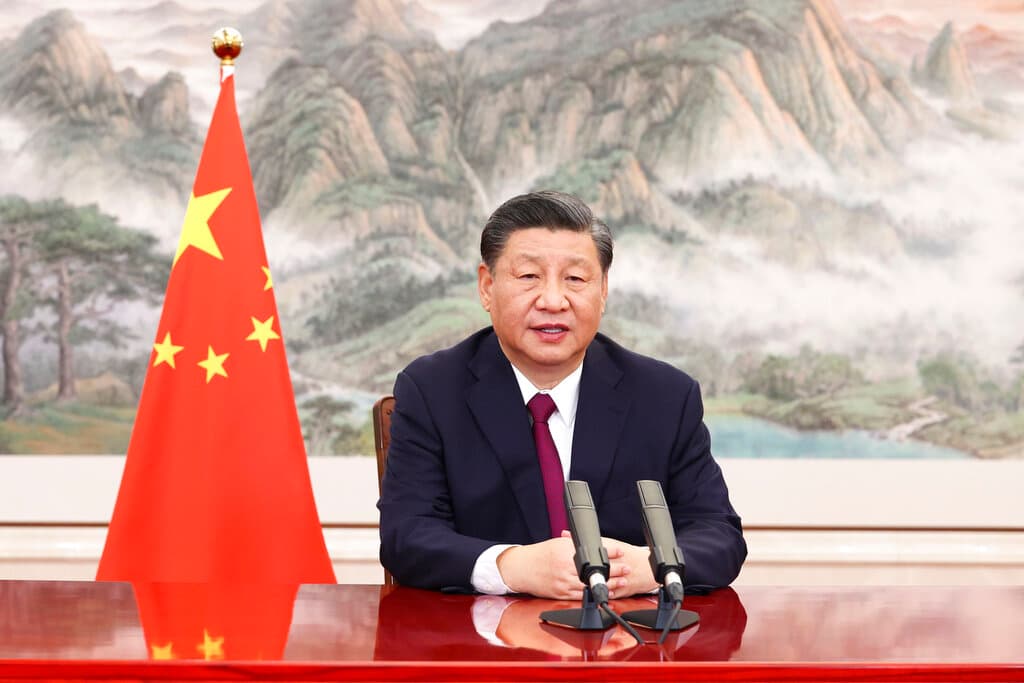

Chinese Party Gets Ready To Crown Its Dictator

Although all eyes may be on the Party Congress, the actual decision-making will happen at the annual August gathering of party elders and higher-ranked officials at Beidaihe.

All eyes are on the Chinese Communist Party leadership this year, as the months count down to autumn’s National Party Congress, where Xi Jinping may be crowned for a third term. Already, the speculation is intense. The party boss is in trouble, some analysts say, as rival factions seek to constrain him. They say his premier, Li Keqiang, aims to undermine him and that progressive elites – such as they are – wish nothing less than to deny him history.

Yet those who float such ideas appear not to realize that the assertions are inconsistent with the internal operating logic of the Chinese Communist Party – that, across party, military, and state lines, President Xi is in control. Further still, in communist states it is the communist ideas, not those of supreme leaders, that matter most. Even in the unlikely event that Mr. Xi would be deposed, China would not be fundamentally altered. The party would retain the same strategic outlook that has guided it since the days of Mao Zedong.

As with most such speculation, though, there is some truth being aired. Mass lockdowns instituted under Mr. Xi’s “zero-Covid strategy” have heralded a humanitarian and economic crisis. Public discontent is mounting, and loyalty to China’s communists is, to an extent, waning. President Xi’s embrace of the Russian president has also elicited pushback from some Chinese elites – and, should the commentariat be believed, Communist Party members.

All the while, China’s housing market is nearing collapse, Western companies – most recently Apple – are moving parts of their investments out of the country, and China’s much-lauded science industry has failed to produce a Covid-19 vaccine on par with its Western peers. In most states this amalgam of events would imperil the top brass.

China is not most states.

Mr. Xi’s aggregation of power over the last decade has been so complete that he is unlikely to pay a significant political price for his blunders. Just last month the party issued, in effect, a ban on grumbling, with retired senior members being forbidden from having “improper discussions.” Although outwardly farcical, the move is a strategic one.

While all eyes may be on the Party Congress, the actual decision-making will happen at the annual August gathering of party elders and higher-ranked officials at Beidaihe. Succession in Communist China is, well, very communist, whereby a conclave of chosen elders – most descendants of the “eight immortals” – select the next man for the job.

Until recently, party norms permitted elders to express their displeasure with policies and, on the rare occasion, leadership, in ways that did not tip into open revolt. Factional signaling by, say, applauding policies otherwise marginalized by the party, was tolerated. Mr. Xi’s directive on grumbling, then, is an ostensible ban on the informal ways in which elders conspired with one another. Absent such informality, the party is a well-sealed echo chamber. Absent such informality, too, Mr. Xi’s fate is also likely sealed.

Factional explanations also suggest that there is little reason for China’s party boss and his premier to turn on each other. Unlike Mr. Xi, the party princeling, Mr. Li is a commoner. Even if he did harbor designs against his superior, he would likely struggle to muster support among the party elite who believe, à la George Orwell, that “some animals are more equal than others.” Messrs. Xi and Li are also allies against the Jiang Zemin faction, which in 2012 attempted an ostensible coup against Hu Jintao and General Secretary Xi. Splitting the Xi leadership would only benefit the Jiang clique.

Tracking speculation about factional rumblings in the Chinese Communist Party is valuable. Just as tracing the activities of China’s military lends insights into its aims and capabilities, information about party elites provides insights into regime stability. Yet such information should not yield to fanciful thinking about leadership change and a China transformed. Xi Jinping’s grip remains firm – political rumblings aside.

Even in the unlikely event that Mr. Xi would be denied his historic third term, this would in any case not matter much. Since 1954, when Mao Zedong defined the Chinese Communist Party as the “core force” of the communist cause, and Marxism-Leninism as its “theoretical foundation,” the party has been guided by this ideological persuasion.

Mao engineered the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution in the name of communist ideals. Deng Xiaoping conducted the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign and the Tiananmen Massacre. Messrs. Jiang and Hu together heralded China’s high-tech surveillance state and its accompanying repression. Today, Xi Jinping’s policies – whether on Covid or Hong Kong – are logical extensions of a model of governance that has been decades in the making. Ousting Mr. Xi would likely not alter this trajectory.

Indeed, the challenge that China poses is not embodied in the solitary figure of Xi Jinping. Rather, it is rooted in the party’s ideology. Removing Mr. Xi as the party’s general secretary would not eliminate this wider challenge. In this, the free world must remain clear-eyed and not allow itself to be swept up by the rumor mill. Hoping that Mr. Xi goes away accomplishes little. In any event, it looks like he’s not going anywhere.