‘Carville’ Looks at a Political Consultant Daring To See Reality and Praise ‘Hucksterism’

Documentary shows how the Ragin’ Cajun thrives around those who disagree.

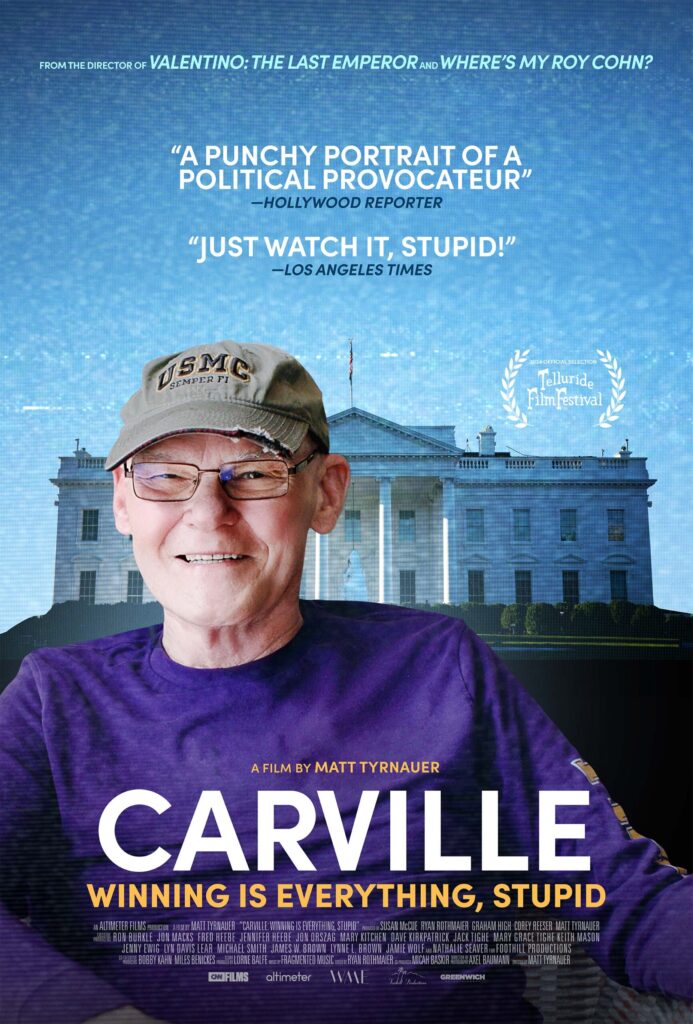

Those who wish to catch “Carville: Winning Is Everything, Stupid” will have to visit Manhattan’s IFC Center. The documentary will trickle into other theaters through Election Day before a December 3 release on Max nationwide. It’s an appropriate rollout for the Democratic political consultant, James Carville, who’s used to being a lone voice that grows too loud to ignore.

The bulk of “Carville” was produced when Democrats were calling Mr. Carville a “bedwetter” for saying President Biden was too old to run for reelection. The criticism didn’t offend Mr. Carville much even before his party accepted the reality he refused to deny. “I’m five percent offended,” he says, that people “think calling me a bedwetter is going to begin to change my mind.”

Mr. Carville thrives around those who disagree. He married a member of President Bush’s 1992 reelection team, Mary Matalin, in the heat of that campaign. “Carville” provides an intimate look at the couple’s disagreements, and what Ms. Matalin calls the “golden age” before today’s “nonsensical politics.”

The attitude of Mr. Carville, a Marine, reminded me of Major Richard “Dick” Winters in World War II. In a moment immortalized by the film “Band of Brothers,” Winters is warned that he and Easy Company of the 101st Airborne Division will be surrounded on a mission. “We’re paratroopers,” he replies, “We’re supposed to be surrounded.”

The documentary’s title invokes Mr. Carville’s line, “It’s the economy, stupid,” crystalizing the message of President Clinton’s 1992 campaign. Plenty of people tell candidates what they wish to hear or dwell on minutiae.

In “Carville,” we meet a Cajun boy who knows how easy it is to get bogged down in a swamp. “Taking a fight, winning the fight, moving to the next fight,” Mr. Carville says. “That’s what’s important.” It’s a quality Mr. Clinton, and others who know him well echo throughout the film.

Even when Mr. Carville isn’t focusing on President Trump, he’s demonstrating that he understands the mogul’s appeal as no other foe does. He speaks with fondness about the colorful Louisiana politicians of his youth, who made fortunes selling cars and snake oil. One candidate, Price LeBlanc, taught him “the value of salesmanship and hucksterism,” he tells a class, “and Democrats, we’re not huckster enough.”

Mr. Carville describes his mother, Lucille “Miss Nippy” Carville, as “a great salesperson” and “huckster” who peddled encyclopedias door to door, targeting houses with bass boats and bicycles because it indicated disposable income and children. Mr. Carville feels America has “come to devalue salesmanship,” but “if you’re not willing to sell, you’re not willing to win.”

Today, titles like consultant, strategist, and advisor are bestowed on anyone who ever brought a candidate coffee. The goal is to achieve the celebrity Mr. Carville earned while skipping the phase that finds him sleeping on the couch of his partner, Paul Begala, at 40. This origin story in “Carville” is compelling because its subject never dreamed that his journey would end at the White House.

In a 1990 Senate race, Mr. Carville earned his first win. He was 42. From there, he helmed the Clinton War Room. He’s shown in tears on election night, having helped end the GOP’s 12-year streak in the White House. The conventional wisdom is that the independent candidate, Ross Perot, cost President George H. W. Bush reelection. “Carville” shows a pugilist who’d have relished a one-on-one fight.

Mr. Carville grew up in a Louisiana town so small, it has just a single stop sign. It’s called Carville not because the family was “land barons,” the consultant says, but because his grandfather was the postmaster, and the name stuck. “We were low-level bureaucrats,” he explains, who could “get into any club” but “couldn’t pay the dues.”

Residents of Carville, Black and white, are happy to see their local hero walking around but not surprised. He walks for much of the film, including with presidents, but he’s born on the Bayou, never being consumed by the “Rajin’ Cajun” caricature of the press. He and Ms. Matalin prefer writing books and speaking over being lobbyists.

Watching interactions with people in “Carville,” I was reminded of President McKinley, who it was said kept “his ear so close to the ground, he has grasshoppers in it.” It’s a posture that enables Mr. Carville, when confronted by challenges such as Mr. Clinton’s letter about avoiding the Vietnam War draft or the contemporary Democratic focus on what he calls “woke” issues, to see a path forward.

The director of “Carville,” Axel Baumann, and his editor, Ryan Rothmaier, do a service by illuminating so much of Mr. Carville’s life beyond the Beltway. Viewers tend to take good production values for granted the way New Yorkers just expect good pizza. It’s worth pausing, though, to appreciate how the film meets the challenge of distilling a long and vivid public record into a taut narrative.

“Carville” is an immersive look at an architect of our current era of Democratic dominance where only one Republican has won the popular vote since 1988. Mr. Carville feels “a little odd” being “the person that popularized the word ‘stupid’ in American culture.” When this documentary grows too big to ignore, though, he can be confident that Americans will remember him for much more than a slogan.