Calling All Gun Historians

Judges are increasingly looking to the past to chart the future of firearm jurisprudence.

A recession could be coming to America, but it appears that boom times are ahead for historians, at least those who specialize in guns. That possibility emerged as a federal district court judge in Mississippi, Carleton Reeves, snapped back at the Supreme Court.

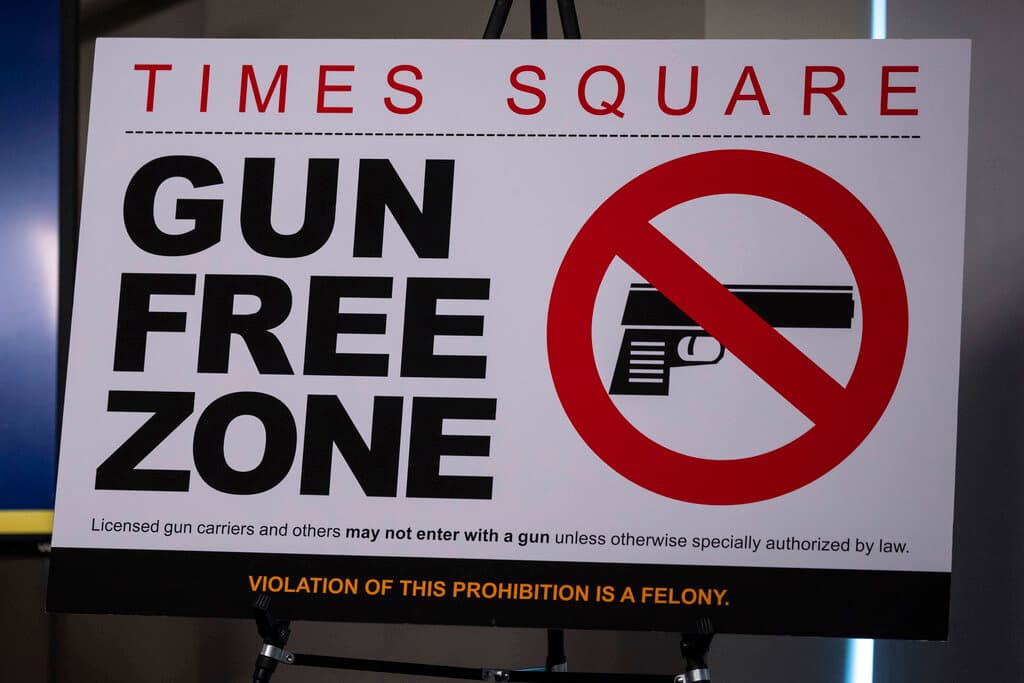

The target of Judge Reeves’s ire was New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, decided in June. In Bruen, the Nine struck down a set of Empire State gun licensing requirements as unduly onerous and an impermissible infringement on the Constitution’s promises of “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms.”

A login link has been sent to

Enter your email to read this article.

Get 2 free articles when you subscribe.