Bloomsday in New York, With James Joyce

‘Ulysses’ is among the least inevitable of classics — migraine inducing, obscene and kinky, pretentious, and unique.

James Joyce wrote “Ulysses,” the great Irish novel, in continental Europe, so it is just as well that New York City is staging a generous show of the man in full, in all his bawdily voluminous brilliance. The host is the Morgan Library, the cache is enviable, and the man it brings into focus is not a starchy old master but a language obsessive, an Irish exilic bard, and a literary wild man.

“One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses,”’ which opened June 3 and runs through October 2, marks the centennial of what the editorial board of Modern Library named the greatest novel of the last century. “Ulysses” is among the least inevitable of classics — migraine inducing, obscene and kinky, pretentious, and unique.

The author of some of the most daring writing of the 20th century, Joyce changed not only what novels could do, but what they could be. “Ulysses” covers a single day, kaleidoscoped through the eyes of a range of Dubliners. Built along the lines of Homer’s epic of wandering, “Ulysses” boldly shucked off the conventions of the Victorian novel to create a modernist monument.

This is why “Ulysses” has always been a totem as much as a novel. The Morgan’s “James Joyce” does justice to that status by gathering manuscripts, correspondence, and paraphernalia. The book, which Joyce began in 1914 and finished in 1921, is set on June 16, 1904, a day that has come to be known as “Bloomsday” after the novel’s protagonist, Leopold Bloom, a half-Jewish Irishman and one of literature’s greatest creations.

“One Hundred Years” is curated by Colm Toibin, the prolific Irish author, and the catalog features an introductory essay from Ireland’s president, Michael Higgins. Even for a country with no shortage of literary lights — Oscar Wilde, William Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett, and Seamus Heaney — Joyce remains essential.

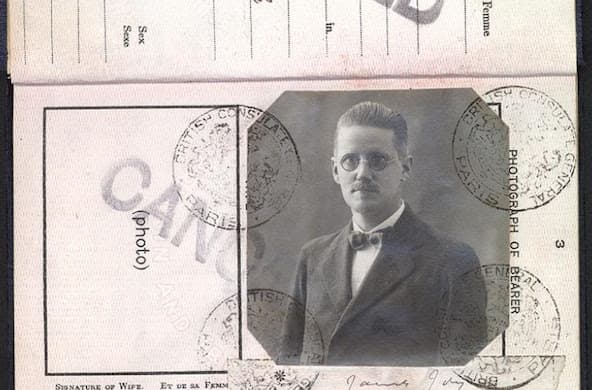

To swipe a title from one of Joyce’s early works, the show begins with a portrait of the artist as a young man. Of his father, John Satinslaus Joyce, who hailed from Cork and with whom the writer enjoyed warm relations, the younger Joyce said, “I got from him his portraits, a waistcoat, a good tenor voice, and an extravagant licentious disposition.” Joyce said of “Ulysses” that its people are his friends. The book is his father’s “spittin’ image.”

Joyce would become a Prometheus of prose, but his first loves were lyrical poetry and music. There are crinkled juvenilia on display, the work of his college years, often scotched by administrators because of references to sex in a preview of the battle to publish “Ulyssess” that would eventually be decided not at the printing presses but in the courtroom.

One short poem, “The Holy Office,” was controversial not for the sin of lust but rather for impertinence. It takes aim at more senior writers like Yeats and George Moore, and announces a new talent on the scene: “they have crouched and crawled and prayed/I stand, the self-doomed, unafraid/Unfellowed, friendless and alone/Indifferent as the herring-bone.”

The path from cheeky apprentice to Irish magus would take Joyce away from his homeland. Joyce met his wife Nora Barnacle in 1904, though they would not officially marry until 1930. His letters to her burn with a still palpable passion. They moved to Trieste, where Joyce eked out a living teaching English, which for his students would be akin to taking guitar lessons from Jimi Hendrix.

Joyce spent the World War in Zurich, and in 1920 decamped to Paris, where he would live until 1940. Alongside the productivity that brought the world “Dubliners,” “Portrait of An Artist,” “Ulysses,” “Finnegan’s Wake,” a raft of poetry, and one unsuccessful play, Joyce battled failing eyesight and his daughter Lucia’s psychological struggles.

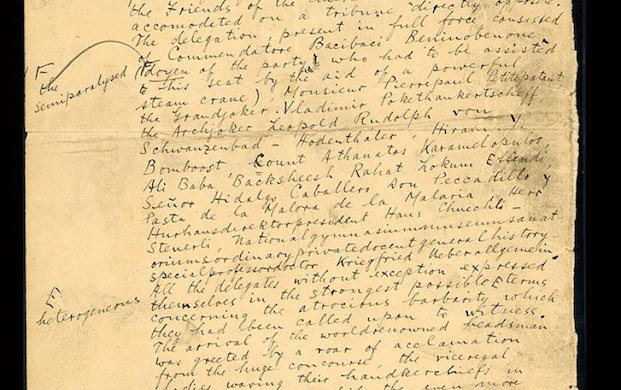

“One Hundred Years” really lifts off when it turns to the making of “Ulysses.” We see Joyce’s hand scratching endless annotations, the blood vessels, ligaments, and bones of a work long in gestating. Of particular interest are his “schema,” coded blueprints of themes, characters, and locations that show the shape of “Ulysses” as it took form in Joyce’s head.

That shape was labile and sprawling. A wall note discloses that the Joyce scholar Luca Crispi in 2019 tallied 39 handwritten drafts, more than 1,400 pages of typeset, 5,000 pages of page proofs and galleys, not to mention a final manuscript of more than 800 pages. In a present when much language lives in the cloud, these numbers offer a salutary reminder of writing as a kind of manual labor.

“One Hundred Years” revolves around Joyce, but it also situates him within a broader avant-garde. The painter Henri Matisse illustrated a version of “Ulysses,” and the poet Ezra Pound was one of Joyce’s champions, as was T.S. Eliot, who wrote an early review of “Ulysses” that labeled it “the most important expression which the present age has found.”

Most important of all was the publisher and owner of Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, Sylvia Beach. “Ulysses” had been serialized in the Little Review in America, but in 1921 the magazine was banned from these shores under obscenity laws. In the 1920s, the Postal Service burned copies of “Ulysses” when it found them.

The turning point came in 1932, with a case in federal court, United States v. One Book Called Ulysses. Judge John Woolsey ruled that “Ulyssess” was not pornographic and that it thus could not be banned as obscene. The judge failed to detect in it the “leer of the sensualist.” For Joyce to have self-censored in the name of proprietary would have been “artistically inexcusable.” The case remains a landmark of First Amendment jurisprudence.

Joyce’s biographer, Richard Ellman, describes how “Ulysses” gives readers a Dublin that “rises in bits, not in masses,” as if with a GoPro built from dizzying lines of prose. He also reports that when Joyce heard of Judge Woolsey’s holding, the author exclaimed “one half of the English speaking world surrenders; the other half will follow.”

That surrender is long since complete. In a famous line, one of the central characters in “Ulysses,” Stephen Dedalus, remarks, “I fear those big words, which make us so unhappy.” Time spent at “One Hundred Years” is a reminder of the alchemy of words large and small, sense and nonsense, that took a map of Dublin and made a world.