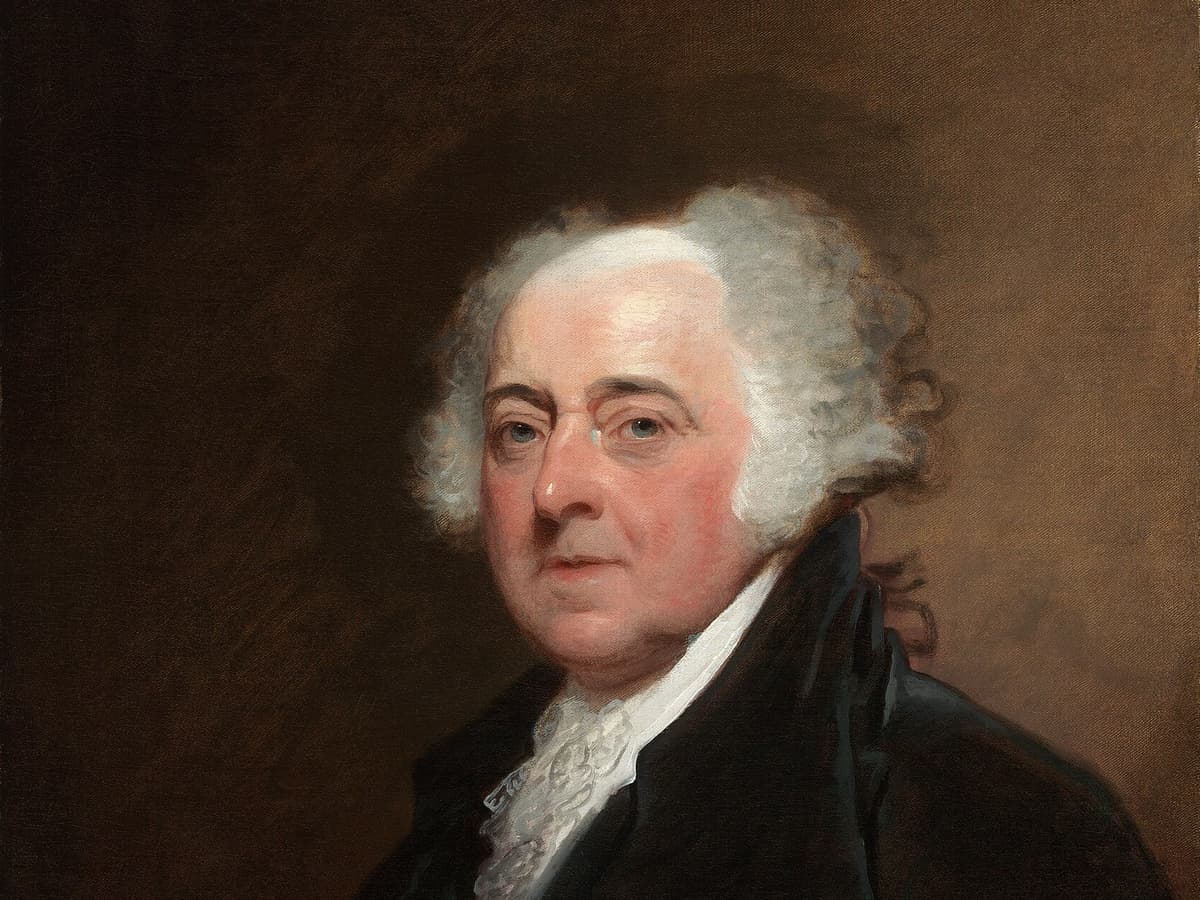

Biography Offers a Revisionist Take on the Presidency of John Adams

The most disturbing element in the book is Thomas Jefferson’s behavior in the election of 1800, when he met with Adams and threatened violence if the Republicans were denied power.

‘Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents That Forged the Republic’

By Lindsay M. Chervinsky

Oxford University Press, 440 pages

In 1797, John Adams became the second American president, having won election by three votes in the Electoral College. Although George Washington had set a momentous precedent by relinquishing power — as no other leader of his epoch had done — much of what a president was supposed to do, notwithstanding the Constitution, was at that point vague and the subject of debate.

As Lindsay Chervinsky explains, Washington provided virtually no assistance in the transition to the Adams administration. He had rarely met with Vice President Adams, did not include him in Cabinet meetings, and, for unaccountable reasons, decided not to share his thoughts about the future with Adams.

Adams made the fateful decision to retain Washington’s Cabinet, seeking to maintain continuity in the two administrations. Unfortunately, a faction in the Federalist Cabinet undermined the new president. John Hancock named the conspirators the Essex Junto, as this group had its origins in Essex County, Massachusetts, and was part of an extreme opposition to Thomas Jefferson and his preference for France in its rivalry with Britain.

How much Adams knew about the plotting against him is hard to tell, Ms. Chervinsky notes. In her account, the president proceeded in good faith and did not replace any Cabinet members until the last year of his presidency.

The chief villain in the anti-Adams cabal was the secretary of state, Timothy Pickering, who believed Cabinet members were autonomous agents not beholden to the president. Pickering confided to Alexander Hamilton what Adams intended to do, especially in reference to France, which had turned hostile to America and was apparently preparing for war.

Pickering, in collusion with Hamilton — who hated Adams as much as Adams hated Hamilton — strove to make the Federalists a war party answerable to Hamilton, who had Napoleonic dreams of glory, hoping to incite a conflict that would supply the rationale for building up the American Armed Forces.

In Ms. Chervinsky’s telling, Adams gradually caught on to the Pickering-Hamilton connivery, and he masterfully built up the Navy as the nation’s bulwark while thwarting efforts to amass the very expensive, 50,000-strong soldiery that Hamilton proposed.

Although Adams, put out with the French, dangled the threat of war, he bided his time and negotiated a peace treaty that was much to the advantage of an America that could not afford to become entangled with the might of a European army.

What distinguishes Ms. Chervinsky from other Adams biographers is how much persuasive detail she puts into what is, in effect, a rehabilitation of President Adams, often maligned by historians who have absorbed, she contends, too much of Jefferson’s Republican propaganda.

Adams’s presidency, Ms. Chervinksy observes, has too often been given slight attention in biographies of him that focus on his outstanding contributions to the American Revolution. She acknowledges Adams’s prickly and volatile personality, but argues that in the main he was right on the issues, and provided the precedent for a peaceful transfer of power — the first time a president who had lost an election had to do that.

The most disturbing element in Ms. Chervinsky’s book is not the villainy of Hamilton but Jefferson’s behavior in the election of 1800, when he met with Adams and threatened violence if the Republicans were denied power. Adams, who did not respond to Jefferson’s provocation, extended his assistance in the transition of power, rectifying the omission of doing so when Washington had departed the presidency. Ms. Chervinsky adds that Jefferson, to his credit, made every effort to begin his term of office pledging to work with all parties.

All Adams biographers acknowledge the crucial comfort and aid of Abigail Adams, but Ms. Chervinsky continually shows how at virtually every significant moment in the Adams presidency he relied on her advice. When she could not join him — she was often superintending the family farm — he was almost desperate for her counsel and company.

Unlike previous Adams biographers, Ms. Chervinksy has little to say about Adams’s life before and after his term as president. As a result, she is able to provide a powerful portrayal of the nuances of governing that shows John Adams to be a far more formidable and wise figure than has hitherto been apparent in presidential biography.

Mr. Rollyson’s work in progress is “Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History.”