Bernanke’s Prescription for Inflation — Give the Fed More Power

‘In a fiat-money system — one in which money is not backed by a physical commodity such as gold — it is not possible for a central bank to leave asset prices and yields entirely to the free market.’

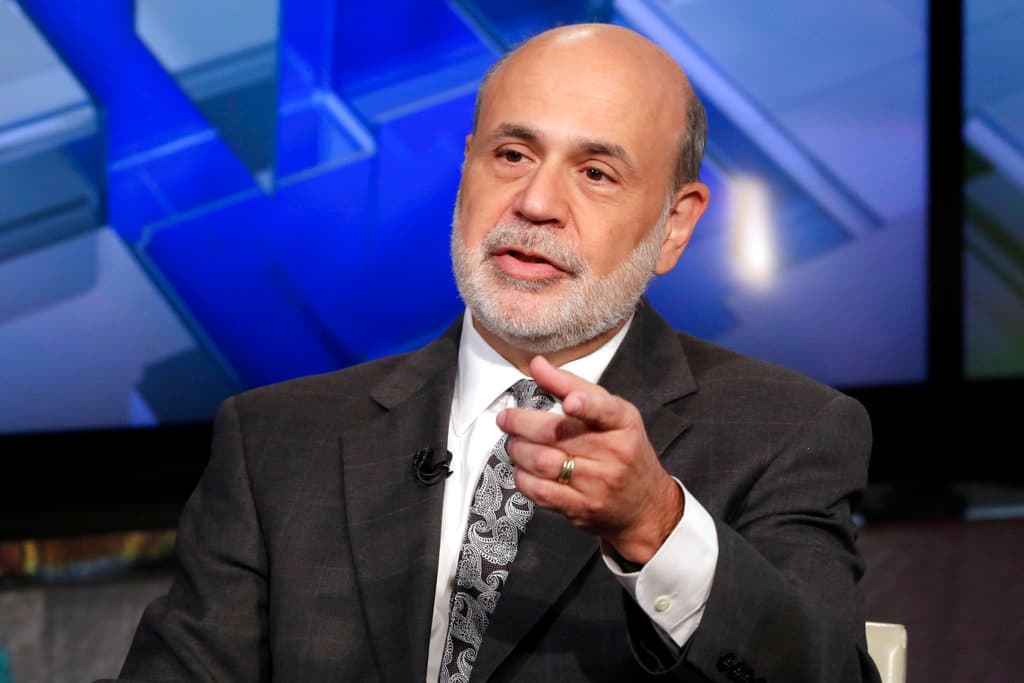

Let’s see. Inflation currently exceeds 8 percent a year in the United States. Our central bank, the Federal Reserve, is sitting on roughly $9 trillion in financial assets — most of them U.S. Treasury debt obligations — that it purchased with money it created for just that purpose. And along comes a new book by a former Fed chairman, Ben Bernanke, seeking to explain and exalt how we got here.

It turns out that Mr. Bernanke’s tome — wait for it — hails all the innovations of the last few decades that have enlarged the Fed’s “toolkit.” That’s Fed-speak for the alarmingly powerful authorities granted to, or seized by, unelected central bankers. Mr. Bernanke has produced the perfect sequel to his earlier paean of self-praise, “The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath.”

This new memoir, “21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19,” is out just as President Biden, and two of Mr. Bernanke’s successors — Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and the current Fed chairman, Jerome Powell — huddle in a desperate bid to figure out what to do about inflation. And what is the basic premise that Mr. Biden might take from Mr. Bernanke’s latest volume?

It is that the Fed has gained its enhanced powers to hold sway over economic activity as a direct result of various financial crises that have occurred since the late 1970s through the present. They all served to amplify the Fed’s influence; he is plenty okay with that.

Monetary wonks will find Mr. Bernanke’s elaborations on data analysis and policy deliberations quite riveting even as constitutionalists will bristle at his breezy assertions to justify government intervention.

“In a fiat-money system — one in which money is not backed by a physical commodity such as gold — it is not possible for a central bank to leave asset prices and yields entirely to the free market,” Mr. Bernanke writes. “It must set some policy regarding interest rates and the money supply, which in turn inevitably influence market outcomes.”

Also inevitable, once the Fed has been put in the driver’s seat, is an expansion of the central bank’s regulatory powers. Mr. Bernanke performs a neat sidestep in citing a “flawed regulatory system” for the 2008 global financial meltdown that took place on his watch. He goes so far as to refer to the “blind spot” of his predecessor, Alan Greenspan: “His error was that he trusted too much in market forces, including the self-interest of bank executives and boards, to limit bad lending and excessive risk-taking.”

What about the low interest rates engineered by an activist Fed during the years prior to the collapse, between 2002 and 2004, when Mr. Bernanke was serving as a Fed governor? Mr. Bernanke took over as Fed chair in January 2006; in June 2006, he ended the long sequence of quarter-point rate hikes that had begun in June 2004 under Mr. Greenspan. Does the Fed bear culpability?

“Most economists believe that monetary policy was at best a minor source of the 2007-2009 crisis,” according to Mr. Bernanke. He attributes the great financial panic to “other factors” — mass psychology, Wall Street financial innovation, and ineffective financial regulation — with only the slightest concession that “monetary policy does seem to influence risk-taking.”

Yes, well.

Then we are off to the races as the Fed chief responds — heroically, if he does seem to suggest so himself — to central bank failures by expanding central bank powers. “Whatever the source of the housing bubble,” states Mr. Bernanke with no sense of irony, “once it took shape monetary policymakers faced a difficult call.”

That difficult call was met by adding two additional “tools” to the Fed’s toolkit (sorry) that amounted to 1) purchasing massive amounts of U.S. government-backed debt and 2) dropping more hints to savvy investors about the likely future path of interest rates. Or as Mr. Bernanke puts it, the Fed leaned heavily on 1) “large-scale quantitative easing” and 2) “increasingly explicit forward guidance.”

How did that all pan out? Read Mr. Bernanke’s book to comprehend how central bankers can somehow take pride having choreographed the subsequent six years of sluggish growth and high unemployment as they continued to maintain near-zero interest rates and expand the Fed’s balance sheet. It’s all there.

He touches on Janet Yellen’s turn at the helm after 2014 and the delayed liftoff for “normalizing” rates; there would only be two quarter-point hikes through the end of 2016. An entertaining chapter on “Powell and Trump” details how Fed chairman Jerome Powell struggled mightily against “caving” to Trump’s demands for lower rates in 2019—before cutting them three times.

The most ominous chapters are entitled “Is the Fed’s Toolkit Enough?” and “Making Policy More Powerful: New Tools and Frameworks,” found in the final section. Spoiler alert: Mr. Bernanke deems the risks of Fed intervention “manageable” and urges monetary policymakers to “continue their search for new tools and strategies.” For this consummate government technocrat, the only real sin would be to constrict the Fed’s “policy space.”