Auction Price Could Rank Warhol With the Greatest of the Masters

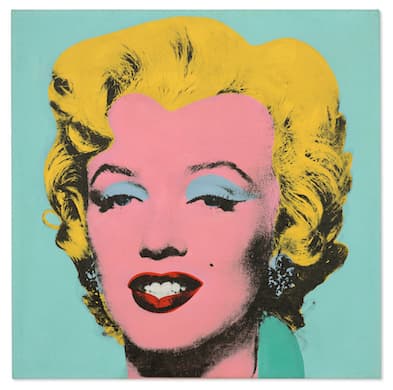

‘Shot Sage Blue Marilyn,’ created in 1964 and based on a publicity still from the 1953 film ‘Niagara,’ was one of dozens of images Warhol made of Marilyn Monroe.

Ondrej Warhola was an immigrant from Slovakia who landed in Pittsburgh and labored in a coal mine. A painting by his son of the most famous movie star in the world, “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn,” is set to shatter the auction record for a 20th century painting this May. It is a tale so fabulous that Andy Warhol probably would have invented it, if it weren’t true.

The painting is expected to fetch on auction at Christie’s at least $200 million; it is believed that even higher prices for 20th century works of art have been achieved in private sales. The seller, the Thomas and Doris Ammann Foundation in Zürich, will direct proceeds to charity.

The overall auction mark of about $450 million was set by the “Salvator Mundi,” whose attribution to Leonardo da Vinci has been much disputed. It was likely bought by the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman himself. The Wall Street Journal has reported that it was spotted aboard the crown prince’s yacht, and is now at an undisclosed location in the Kingdom.

“Shot Sage Blue Marilyn,” created in 1964 and based on a publicity still from the 1953 film “Niagara,” was one of dozens of images Warhol made of Marilyn Monroe. The celebrity fascinated this artist, who more than any other saw art as part and parcel of the mass-produced marketplace.

“Shot Sage Blue Marilyn,” which measures 40 inches square, is one of a series of five Warhol crafted with a variation of his signature silkscreen technique.

The portrait’s name comes from another almost impossibly good story. The paintings were stacked at the Factory, Warhol’s iconic studio that was then on 47th street — in 1967 it would move to 33 Union Square West. A performance artist named Dorothy Podber, loosely affiliated with Warhol’s group, asked if she could shoot the paintings.

Warhol, assuming she meant a photograph, agreed. She put a bullet through four of them, including the one due to sell for a mint in May; the turquoise one was spared. Warhol attempted to paint over the holes. Podber never set foot in the Factory again, but the paintings became famous.

A fellow traveler, “Shot Orange Marilyn,” also has gone on to an especially lucrative career, purportedly sold to hedge fund magnate Kenneth Griffin for well more than $200 million.

The chairman of Christie’s department of 20th century and 21st century art, Alexander Rotter, has no doubt that “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn” belongs on the Olympus of art history.

“Standing alongside Botticelli’s ‘Birth of Venus,’ Da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa,’ and Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,’” Mr. Rotter proclaims in a statement, “Warhol’s ‘Marilyn’ is categorically one of the greatest paintings of all time.” He argues that this sale will alter “not only Warhol’s market, but the market itself.”

Even accounting for an auctioneer’s hyperbole, Mr. Rotter’s comments speak to an art market where a Warhol can outearn an Old Master, and a Non-fungible Token can be valued more than a masterpiece of paint or stone.

The outsize sums spent on art by oligarchs and financial titans serve as often absurdist posthumous jokes on artists whose lives were in fact parlous. Amedo Modigliani was desperately poor, and yet his “Nu Couché” sold for $157 million in 2018. Vincent Van Gogh sank into a madness-streaked penury and yet his “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” fetched more $80 million in 1990. In terms of gold, that would be about $435.7 million today.

Robert Mapplethorpe crafted photographs nobody wanted to see and slummed in Alphabet City attics. Ten years ago, the J. Paul Getty Trust and Los Angeles County Museum of Art bought a cache of his work for $30 million.

The work of a Warhol protege, Jean-Michel Basquiat, garnered $439.6 million at auction in 2021. The student bested the teacher, as Warhol’s works clocked $347.6 million at auction last year.

While these posthumous prices suggest some an almost cosmic settling of aesthetic accounts — all of the above artists are originals — that logic falters when applied to the astronomical sums forked over for something like Jeff Koons’s “Rabbit” three years ago, when hedge fund magnate and Mets owner Steven Cohen paid $91 million for the stainless steel, 3-foot-tall inflatable bunny.

It is easy to imagine Warhol himself, for whom attention was oxygen, enjoying not just the price tag but also the spectacle of the world’s richest people bidding for his work.

The art critic and Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik describes the artist’s protean shape-shifting — “in the ’50s, he’s a gay, fabulous window dresser. In the ’60s, he acquires this leather-jacketed, sphinx-like quality. In the ’70s, he becomes a new conservative.” In 2022, he is, in the auction halls at least, ranked with Rembrandt.