The Father of the Four Hundred

This article is from the archive of The New York Sun before the launch of its new website in 2022. The Sun has neither altered nor updated such articles but will seek to correct any errors, mis-categorizations or other problems introduced during transfer.

Ward McAllister was long the most famous of Manhattan’s social arbiters. McAllister was born in Savannah, Ga., in 1827, but he and his jurist father struck it rich practicing mining law in California during the 1849 Gold Rush. After coming East in 1853 and marrying an heiress, he spent several years in Europe, where he studied wines, haute cuisine, and the etiquette of balls and formal receptions. He moved to New York after the Civil War.

Contractors and speculators had made enormous fortunes in the war. Many newly rich New Yorkers believed their wealth alone entitled them to enter Society – to be elected to exclusive clubs and receive invitations to exclusive social functions. They had a point: America is intrinsically open to the self-made.

But the upper-class society they sought to enter, best described in Edith Wharton’s novels and memoirs, largely felt social boundaries should be based on “old connections, gentle breeding, perfection in all the requisite accomplishments of a gentleman … and an unstained private reputation.” Nonetheless, some of the Old Guard felt change was inevitable, and someone had to housetrain the parvenus.

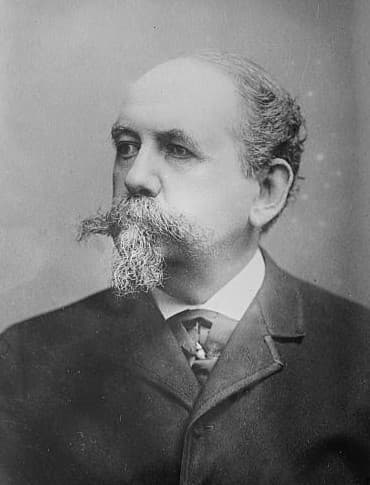

McAllister thought he could create and maintain a self-sustaining aristocracy – rule by the elite – by creating a shared sense of identity among New York’s wealthy families – class consciousness, if you will. No one else had any better ideas. Thus, a short, pudgy, balding Southerner became the arbiter-manager of New York’s high society. Though humorless and pompous (he called a picnic a fete champetre), he was a hardworking, efficient event planner and manager, from invitations (he could spend 10 minutes discussing the wording of an invitation) to having carriages ready for guests’ departure. And, he had the patronage of Mrs. Astor – the Mrs. Astor.

Caroline Schermerhorn Astor had inherited and married money. Intelligent and industrious, she possessed an extraordinary ambition to lead the City’s social elite. Though they were allies, not friends (Mrs. Astor had no intimates), McAllister extravagantly called her “the Mystic Rose,” referring to the heavenly figure in Dante’s “Paradise” around whom all in Paradise revolve.

In 1872, McAllister founded the Society of Patriarchs, a committee of 25 “representative men of worth, respectability, and responsibility” enjoying Mrs. Astor’s support, to unite old and new rich in conducting each season’s “most brilliant balls.” As with any McAllister-directed event, the Patriarchs’ Balls were efficiently managed for the guests’ pleasure.

Invitations, being difficult to obtain, became highly desirable, ensuring that anyone “repeatedly invited to them had a secure social position.” Thus they became the events of the social year. By the 1880s, with McAllister, supported by Mrs. Astor, dominating most society balls’ management committees, they largely determined who was in and out. But McAllister undid himself. On March 24, 1888, he carelessly told the New York Tribune that

There are only about four hundred people in fashionable New York Society. If you go outside that number you strike people who are either not at ease in a ballroom or make other people not at ease … who have not the poise, the aptitude for polite conversation, the polished and deferential manner, the infinite capacity of good humor and ability to entertain or be entertained that society demands.”

Overnight, McAllister found the reporter had defined Society as “The Four Hundred.” Worse, McAllister admitted this number was also the capacity of Mrs. Astor’s ballroom. Yet he hadn’t named names. That happened after four years of titillating the press and public, on the occasion of Mrs. Astor’s ball of February 1, 1892. The list was only 319 names long – including McAllister’s – and consisted largely of bankers, lawyers, brokers, real estate men, and railroaders, with one editor (Paul Dana of The New York Sun), one publisher, one artist, and two architects.

McAllister’s publicity made them celebrities. Some resented it. Their feelings were nothing compared with the rage of those left off the list. Worse, he published his memoirs, “Society as I Have Found It.” McAllister exposed himself as a man of misplaced seriousness, a “dedicated social climber of … comical determination.” He portrayed a life of fighting for the acceptance of those he believed his betters, entering their inner circle, and gaining power to exclude others who shared his ambitions: a string of glittering invitations to dinners, country weekends, and yachting parties. Reviewers savaged him: “The degree of fervor that the author puts into undertakings that adults commonly leave to adolescents is really wonderful.” As one Patriarch later remarked, “Poor McAllister! What a pity it is he wrote a book!”

On January 31, 1895, McAllister died after a brief illness. Only five Patriarchs and less than a score of the Four Hundred attended the services at Grace Church. Mrs. Astor was absent: She had a dinner party that night. Two years later, the Society of Patriarchs, which had been McAllister’s life’s work, dissolved for lack of interest.