Andy Warhol’s 15 Minutes of Fame Run Out at the Supreme Court

A ruling that reads like an Art History term paper pits two giants — Justice Kagan against her fellow liberal, Justice Sotomayor.

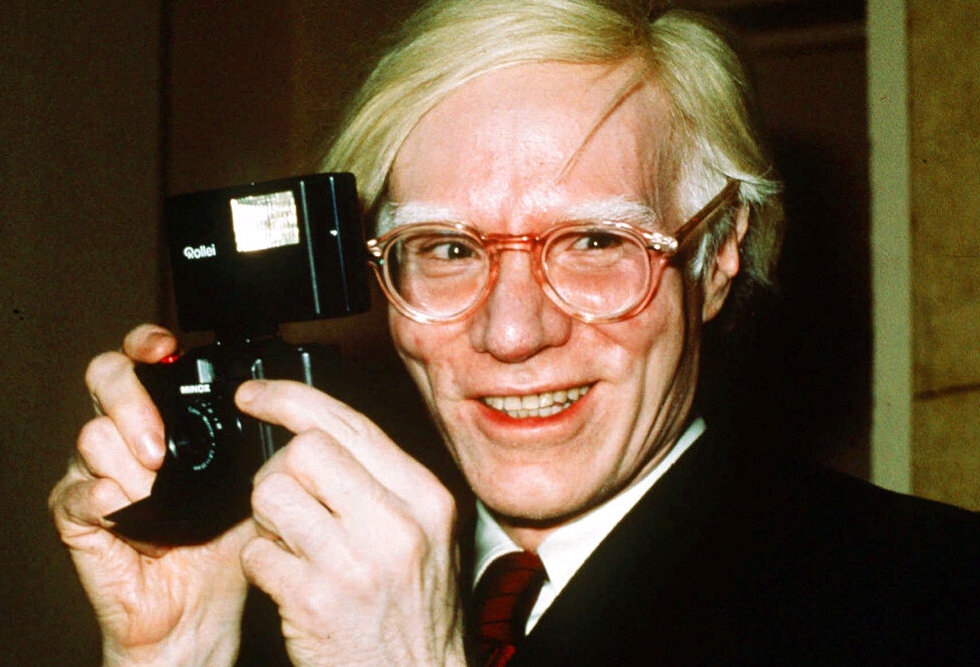

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, a copyright case that touched on the prerogatives of genius and the nature of creativity itself, will reset the rules of the road for artists in an image-saturated culture.

By a 7-to-2 count, the Supreme Court found that the artist Andy Warhol’s appropriation of photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s images of the musician Prince violated fair use, and thus trespassed on copyright’s bounds. It appears as if all is not fair in Pop Art.

An unlikely pair of dissenters — Justices Elena Kagan and Chief Justice Roberts — write that the ruling “will stifle creativity of every sort,” will “impede new art and music and literature,” will “thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge,” and “will make our world poorer.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority, allows that “Warhol’s contribution to contemporary art is undeniable,” but also notes that Ms. Goldsmith was a “trailblazer” who “began a career in rock-and-roll photography when there were few women in the genre.” In other words, it’s a case involving not one artist, but two. Both are accomplished, the man an icon, the woman a pioneer.

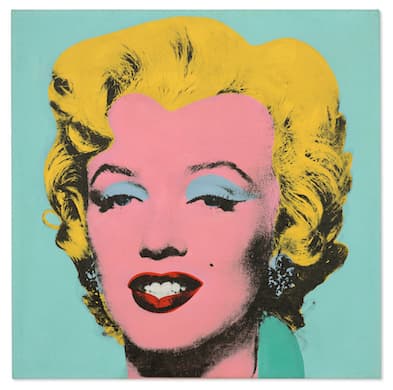

The road to high court from darkroom began in 1984, when Vanity Fair magazine licensed Ms. Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince to illustrate an article about the then-avant-garde singer. The license, though, was for one-time use. Vanity Fair also hired Warhol, who turned the photo into a silk screen.

So far, so good, as Ms. Goldsmith was paid for Warhol’s use of her image. Warhol, though, made 15 more Prince silkscreens from that Ur-image. His foundation licensed one of those to Condé Nast — which owns Vanity Fair — for $10,000. A blizzard of suits ensued, with the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit siding with Ms. Goldsmith.

The case has taken so long to reach the Supreme Court because Ms. Goldsmith did not know about the “Prince Series” — 13 silk screens and two pencil drawings — until 2016, when she saw “Orange Prince” on a Vanity Fair cover, an artistic descendent of her original black-and-white photograph from three decades earlier.

While the Andy Warhol Foundation no longer owns the Prince Series, it asserts copyright in them. When Ms. Goldsmith saw Prince, drenched in orange but otherwise an echo of her image, she exclaimed, “It’s the photograph,” meaning her own. She sued for copyright infringement.

The district court was skeptical, finding that Warhol’s iteration of Ms. Goldsmith’s photograph was protected. When put “side-by-side,” the court reasoned, Warhol’s images “have a different character, give Goldsmith’s photograph a new expression, and employ new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from Goldsmith’s.”

The court ordained that “any secondary work that adds a new aesthetic or new expression to its source material is necessarily transformative,” effectively an endorsement of the Pop artist’s repurposing technique — think Campbell’s soup cans and images of Marilyn Monroe.

Riders of the Second Circuit took a less sanguine view of Warhol’s refashioning, rejecting the notion that a “new aesthetic or new expression” is enough to protect the secondary work from infringement. The test, instead, is whether the later piece achieves a “fundamentally different and new artistic purpose and character.”

For the riders, Warhol’s silkscreens fail this standard because “in the narrow but essential sense that they are portraits of the same person.” To protect the silk-screened Prince would be to “create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege.” They write that the “fact that Martin Scorsese’s recent film ‘The Irishman’ is recognizably ‘a Scorsese’ does not absolve him of the obligation to license the original book.”

The high court’s majority agreed that Ms. Goldsmith and Warhol’s work “share substantially the same purpose” — they both were used to illustrate articles in magazines — and that the older artist’s appropriation of it was of a “commercial nature,” weakening the protections it is afforded.

At the core of copyright is a balance that “trades off the benefits of incentives to create against the costs of restrictions on copying.” The Constitution gives Congress the power to “promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

The pursuit of this balance between what Justice Sotomayor calls “creativity and availability” is a matter less of black letter law than judicial intuition. To wit, in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the justices held that “parody needs to mimic an original to make its point,” whereas “satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.”

While the parameters of parody inform another case this term, Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc., Petitioner v. VIP Products LLC, here Justice Sotomayor quotes a sage of the Second Circuit, Pierre Leval, that “new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings” are necessary for fair use. Here, both Ms. Goldsmith and Warhol were after the same thing.

In finding for Ms. Goldsmith, Justice Sotomayor denies that the court’s decision will “snuff out the light of Western civilization, returning us to the Dark Ages of a world without Titian, Shakespeare, or Richard Rodgers.” She notes: “If the last century of American art, literature, music, and film is any indication, the existing copyright law, of which today’s opinion is a continuation, is a powerful engine of creativity.”

The dissenters see things differently, rising to a defense not just of Warhol but of Western art itself. Justice Kagan writes: “Today, the Court declares that Andy Warhol’s eye-popping silkscreen of Prince” is “not transformative” despite the fact that he “reframed and reformulated — in a word, transformed — images created first by others” as the “avatar of transformative copying.”

“That’s how,” Justice Kagan adds, “Warhol earned his conspicuous place in every college’s Art History 101.” She urges the court to “go back to school” for a “refresher course” on Warhol’s ingenuity. She fumes that “it is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care.”

Justice Kagan quotes the novelist Jonathan Lethem for the proposition that “appropriation, mimicry, quotation, allusion and sublimated collaboration are a kind of sine qua non of the creative act, cutting across all forms and genres in the realm of cultural production.” The majority, she asserts, misses the Muse.

The dissent notes that “Shakespeare borrowed over and over and over” before proceeding through an exegesis of visual art, offering close readings — and color images — of Giorgione’s “Sleeping Venus” and Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” and Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” to show how what the literary critic Harold Bloom called “the anxiety of influence” is indispensable to creativity.

In words that could describe both the artists and the jurist, Justice Kagan explains, “Creative progress unfolds through use and reuse, framing and reframing: One work builds on what has gone before; and later works build on that one; and so on through time.”

In a wry rebuttal at the dissent’s learnedness, Justice Sotomayor notes that “The Lives of the Artists” — a canonical Renaissance chronicle from Giorgio Vasari — “undoubtedly makes for livelier reading than the United States Code or the United States Reports, but as a court, we do not have that luxury.”