Alito’s Latest Prophecy

The Supreme Court misses another opportunity to resolve the national feud over the theory of the independent legislature.

The Supreme Court’s action yesterday to uphold Pennsylvania’s election laws against a federal court intervention in a Quaker State election dispute could prove to have more import than meets the eye. The 7-2 ruling left intact a state law that mail-in ballots be dated in order to be counted. The riders of the Third Circuit had deemed that state policy so picayune that it violated federal election law. It raised echoes of 2020’s vote-counting disputes.

Yet what makes this most recent Keystone State ballot-counting controversy newsworthy is that it falls in the context of a national feud over the theory of the independent legislature. That’s the idea, based on Article I, Section 4 of the national parchment, that only the state legislatures can decide the “manner of holding elections,” and there’s nothing that the state courts or governors can do about the rules they set.

Chief Justice Rehnquist is credited with being first to articulate this “independent legislature theory.” In his concurring opinion — joined by Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas — in Bush v. Gore, Rehnquist noted that “there are a few exceptional cases in which the Constitution imposes a duty or confers a power on a particular branch of a State’s government.” Federal elections — presidential and legislative — provide such occasions.

The Constitution’s direction that each state “shall appoint” presidential electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct” was examined closely by Rehnquist. He concluded “the text of the election law itself, and not just its interpretation by the courts of the States” held “independent significance.” He warned against “the general coherence of the legislative scheme” of election law being “altered by judicial interpretation.”

In Rehnquist’s reasoning, the Supreme Court would have every right to evaluate “whether a state court has infringed upon the legislature’s authority” by making changes in voting procedures, whether in races for Congress as for the White House. In 2020, this line of thinking inspired allies of President Trump to file suit after Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court changed state law by voiding the election-day deadline for mailed ballots to be received.

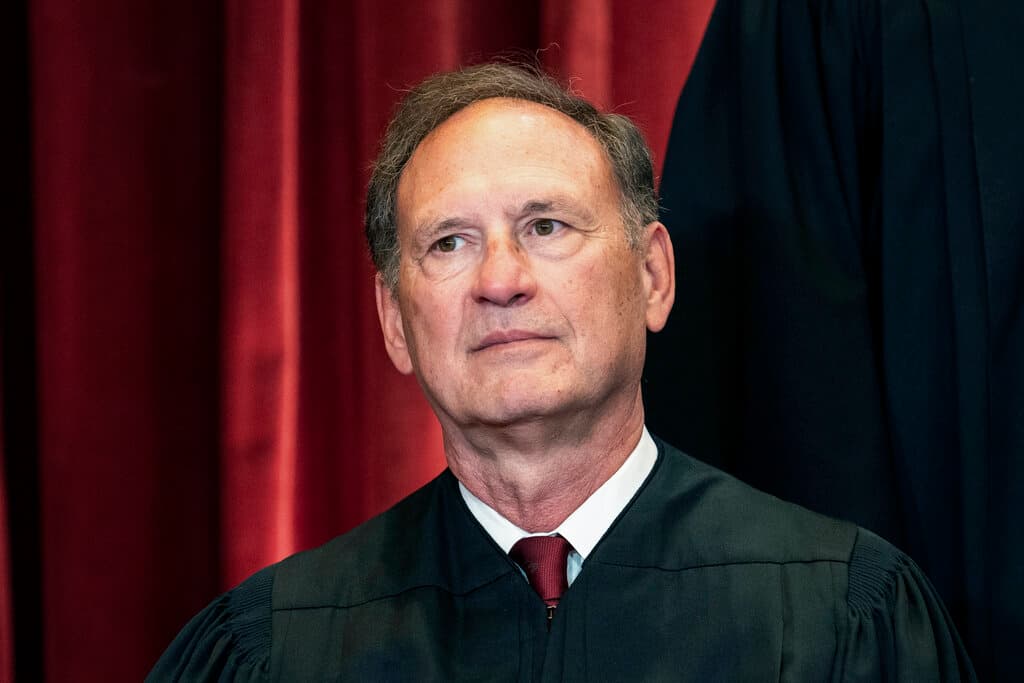

The Supreme Court in late October passed on the opportunity to weigh in on this dispute, which could have affected tens of thousands of ballots, according to NPR, despite Justice Samuel Alito’s warning that letting the matter slide would create “serious post-election problems.” Justice Alito’s plea to at least set aside the ballots received after election day also fell on deaf ears. At the time, we saluted the justice as a prophet.

We also wondered if Justice Alito’s leadership of the dissenters against the action of the Keystone State’s top court stemmed from his seeming “to grasp the possibility of malfeasance in the swamp of Pennsylvania.” We traced this to his prior service as a United States attorney at New Jersey, and having ridden the Third Circuit of the United States Court of Appeals, based at Philadelphia. It could also be, we mused, that he was “just naturally savvier.”

That’s not to mention Justice Alito’s stiffer judicial backbone, as his opinion overturning Roe v. Wade made manifest. In retrospect the wisdom seems even clearer for the Supreme Court to have jumped in before the 2020 election and sorted all these ballot-counting questions out. Not only in Pennsylvania, but in all the states where courts rewrote the voting laws. It might well have avoided a lot of post-election acrimony.

Which brings us back to this latest case, in which Justice Alito in an earlier stage of the litigation again prophesied — this time against letting the Third Circuit meddle with Pennsylvania’s voting laws. He warned that “if left undisturbed,” the circuit precedent could “affect the outcome” of the coming midterm elections. “It would be far better,” he wrote, “for us to address that interpretation before” the voting. It’s likely too late to resolve the independent legislature theory for the midterms, but 2024 awaits.