Accounting for Ernest Hemingway: Does This Search for the ‘Real’ Author Add Up?

Is Curtis L. DeBerg providing a new perspective or fresh evidence? He attempts to do both by suggesting there has been a fundamental misunderstanding of a crucial event in Hemingway’s life.

‘Wrestling with Demons: In Search of the Real Ernest Hemingway’

By Curtis L. DeBerg

Palmetto Publishing, 450 pages

What happens when an accountant decides to write a biography of Ernest Hemingway? We get tables and tabulations of his wounds and his many accidents, his wives’ characteristics, and a careful if repetitive recital of the data, including what’s been uncovered in previous biographies, making this book a handy reference tool.

The first question readers of Hemingway biographies will want answered is whether accountant Curtis L. DeBerg provides a new perspective or fresh evidence. He attempts to do both by suggesting there has been a fundamental misunderstanding of a crucial event in Hemingway’s life that shaped his character and career.

Mr. DeBerg argues that Hemingway’s wounding in World War I after a mortar attack that severely injured his legs was not what traumatized him: Rather, it was his fear that he would be found out as no hero at all, but just a hapless Red Cross volunteer who got too near the front lines when he was warned not to do so.

Mr. DeBerg’s defensible argument relies on circumstantial evidence and a close reading of Hemingway’s conflicting accounts of bravery under fire — including an improbable claim that he carried a soldier to safety in spite of his own grievously wounded legs — and on his hospital nurse’s emphatic statement that he was no hero. Having missed the opportunity to exhibit the grace under pressure that Hemingway cherished, he spent a lifetime seeking redemption for his failure, even foolishly entering a lion tamer’s cage to demonstrate his courage.

This unconventional biography includes fictional scenes that attempt to supply what Hemingway left out of his own stories and dialogues. In these scenes the biographer gets Hemingway to admit that he wasn’t a good husband or father and that he did indeed make up some of his exploits — though even as a ghost Hemingway cannot always bring himself to say so, but rather asks the biographer to watch eye blinks (one for yes, two for no) in response to Mr. DeBerg’s pressing questions.

It might seem imaginable after so many decades after his death that the ghost of Hemingway is finally willing to confess, but wouldn’t the ghost sound at least a little like Hemingway? Instead, he just seems to be there to confirm Mr. DeBerg’s hypotheses — a surprising response from a writer who detested most biographers.

This biography is the result of what might be called a category error, an attempt to use fiction for what a work of nonfiction cannot supply. With fiction, we can suspend our disbelief, as in a biographical novel, but a biography that resorts to fiction simply confuses the categories.

The best parts of “Wrestling with Demons” include the incessant, compelling cataloging of Hemingway’s demons — by which the biographer means his subject’s fears. There, the tables he compiles become dispositive, though why they should interrupt the narrative instead of being placed in an appendix is not apparent.

Mr. DeBerg may have had an advantage over previous biographers: Like Hemingway, not only did he suffer a debilitating air crash — as awful as the two crashes Hemingway experienced — but, like his subject, the biographer has had to live with constant pain and to analyze what that pain did to his psyche and treatment of other people. By making that part of his own story vivid, Mr. DeBerg makes Hemingway’s physical and mental anguish all the more palpable.

Best of all, Mr. DeBerg’s book is situated in the universe of Hemingway biography, so that we learn about major players from Carlos Baker to Michael Reynolds and beyond. Mr. DeBerg makes few errors, though he is mistaken that Martha Gellhorn did not talk about Hemingway with some of his biographers. Both Baker and Jeffrey Meyers obtained her reluctant cooperation. He also misses the irony that Gellhorn — the only Hemingway wife who walked out on him — often sounded like him.

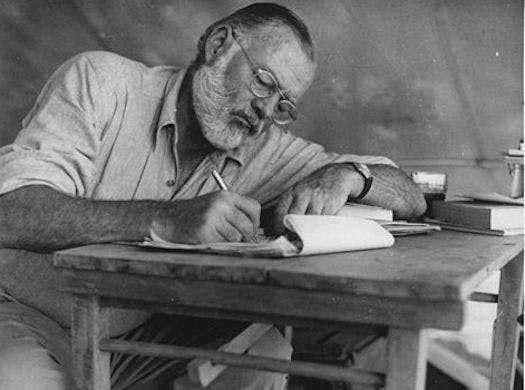

Don’t miss the photographs in this book. It seems that Mr. DeBerg has been everywhere that Hemingway went, so we see what is left of his world and what has changed. This biography’s informal prose style makes for a companionable read, except in those passages that go on too long and repeat too much.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “Nothing Ever Happens to the Brave: The Story of Martha Gellhorn” and “Beautiful Exile: The Life of Martha Gellhorn.”