My Mother, the Nazi Collaborator

A new novel about the oldest hatred paints a portrait of a ‘Rosie the Riveter’ of Vichy France.

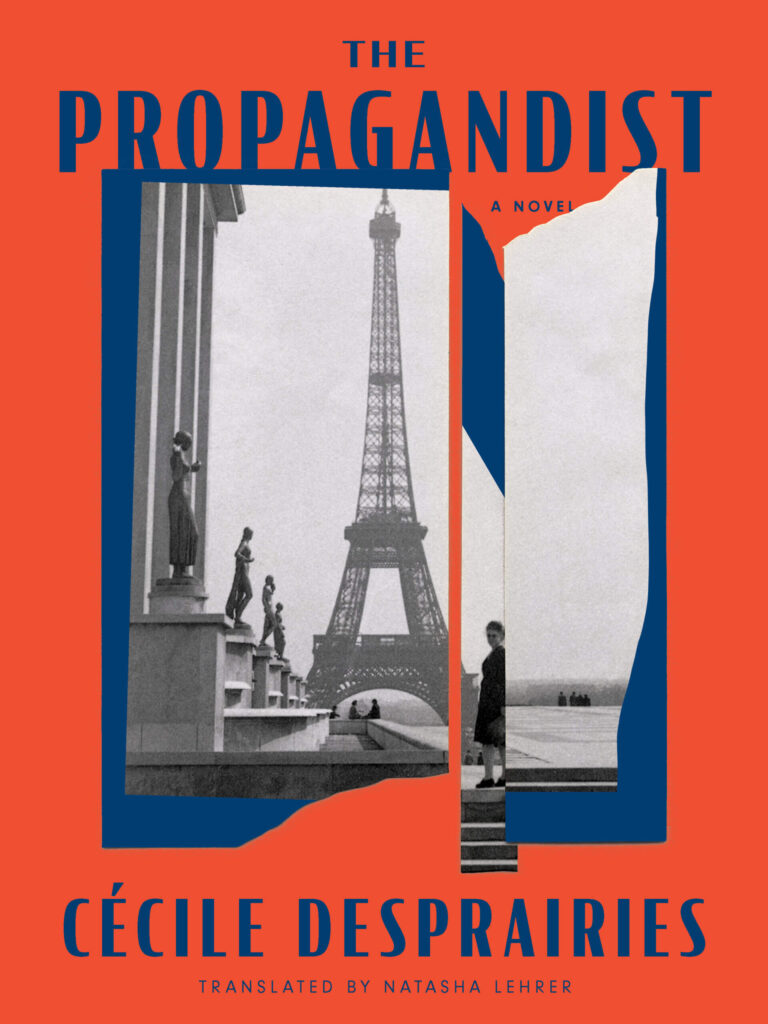

‘The Propagandist’

By Cécile Desprairies

Translated by Natasha Lehrer

New Vessel Press, 208 pages

“The Propagandist” is a tale of Vichy and a return of the French repressed that hits shelves just as the old demons stretch their limbs. A work of sly genre, it slips between fact and fiction to try to capture the truth of French collaboration with the Third Reich. The author, Cécile Desprairies, is a historian of the Nazi occupation of France. Now, in her first novel, she’s crafted an autobiographical story unafraid of the darkness under the City of Light.

The narrator of “The Propagandist” is Coline, an avatar for the author. They both come of age at Paris in the 1960s, a world where the war is everywhere and nowhere, spoken of in sideways code — “apparently this was the way things were for Jews. And Jews were, well, Jews … That was the role of Jews in general: to give away, to part with their possessions.” The book’s center is a charismatic black hole — Coline’s mother Lucie, an unrepentant Nazi.

The Third Republic was invaded by the German army in May of 1940. By June, an armistice agreement had been signed with Hitler. The next day, he took a dawn ride into Paris. Over the course of three hours he visited the Opera, the Champs-Elysees, the Arc de Triomphe, the Eiffel Tower, Napoleon’s tomb, and the Sacre Coeur. Of the approximately 330,000 Jews in France in 1939, 75,000 were deported to concentration camps, most to Auschwitz via Drancy. All but 1,500 of those were murdered.

The book begins with “When I was a child, I would listen to my mother talking softly to herself about ‘the 1940’s.’” Lucie is the center of a circle of aging women, friends and family, that Coline calls “a gynaeceum, the women’s quarters in a house in ancient Greece.” Lucie’s family are pied noirs who left Alegeria decades ago but “have maintained many of the traditions of the Maghreb.” Fascism, though, gives them a fullness, however fleeting.

Hitler’s rise owed much to women, whom he praised as “our most loyal, fanatical fellow-combatants.” This novel tracks Lucie’s fall for a German race scientist, Friedrich, and the ideology to which he is committed. Her daughter recalls that for her mother the “discovery of Nazi ideology had been a profound shock … irrigating life, death, science, culture, politics and behavior.” For Lucie, “The Reich proposed a coherent vision of society.”

Lucie’s passion for Nazism owes just as much to petty resentments as high falutin swooning. “Her schoolmates, from well-to-do families, were almost all Jewish … Lucie would have the last laugh.” She gloats of the disappearances — murder — of “all the Biancas, Simones, Dinahs, and the rest.” She reasons that “it was only the stupid ones who were deported.” From there it is a small step to “Jews were to be treated like tubercular bacilli.”

Lucie rises in Vichy’s propaganda department, moving on the outer circle of the Pétainist elite. She works on picture research and captions for an exhibition called “The Jew and France.” Coline describes her mother as a “collaborationist Rosie the Riveter” who finds her métier designing snazzy graphics for the occupiers. She becomes known as “the Leni Riefenstahl of the poster. Quite an honor.” Liberation brings a “great whitewashing.”

Collaboration defines the entire family. A great-uncle, Raphaël, is an indelible character — “tall, glamorous, flamboyant, imposing, and amusing, he was also venomous and power-hungry.” A gay aesthete, he grows rich taking “whatever he wanted” from the possessions of deported Jews. His favored bon mot is “To each his own … bad taste.” Above the Buchenwald concentration camp hung the German expression Jedem das Seine — “to each their own.”

After the war, Raphaël reflects that “it was idiotic, all this talk of collaboration. Everyone had been involved.” He reckons that Lucie’s “antisemitism had been a failure” because “she had not managed to make a cent out of it.” There was a fortune to be made in the pillaging of European Jewry, but Lucie’s hate is blunt and almost ascetic. Germany’s defeat only powers the persistence of her prejudice. She nurses the Reich’s glory to her dying day.

The book’s signature scene transpires after Liberation. Lucie gathers together her family and friends, all of whom have thrown in with the Germans. Now, it is time to launder the war’s dirty laundry. She declares “we believed, and we still do. This is how things are now. Our enemies are the same, but now we shall have to be discreet.” The most important rule she lays down — “never, ever talk about the Jews. Never, ever use that word.”

As Coline matures she sees that her mother “remained obsessed with the collaboration. She was an ambassador for a lost cause, an empress without an empire, a Gaul without a district.” Lost causes can be the most energizing of all, preserved in amber. What would Lucie make of today’s resurgence of antisemitism in France, the altneu chants targeting the same scapegoats? She’d design the posters.