A Master Painter — Italian, Jewish, and Gay — Returns to New York in Triumph

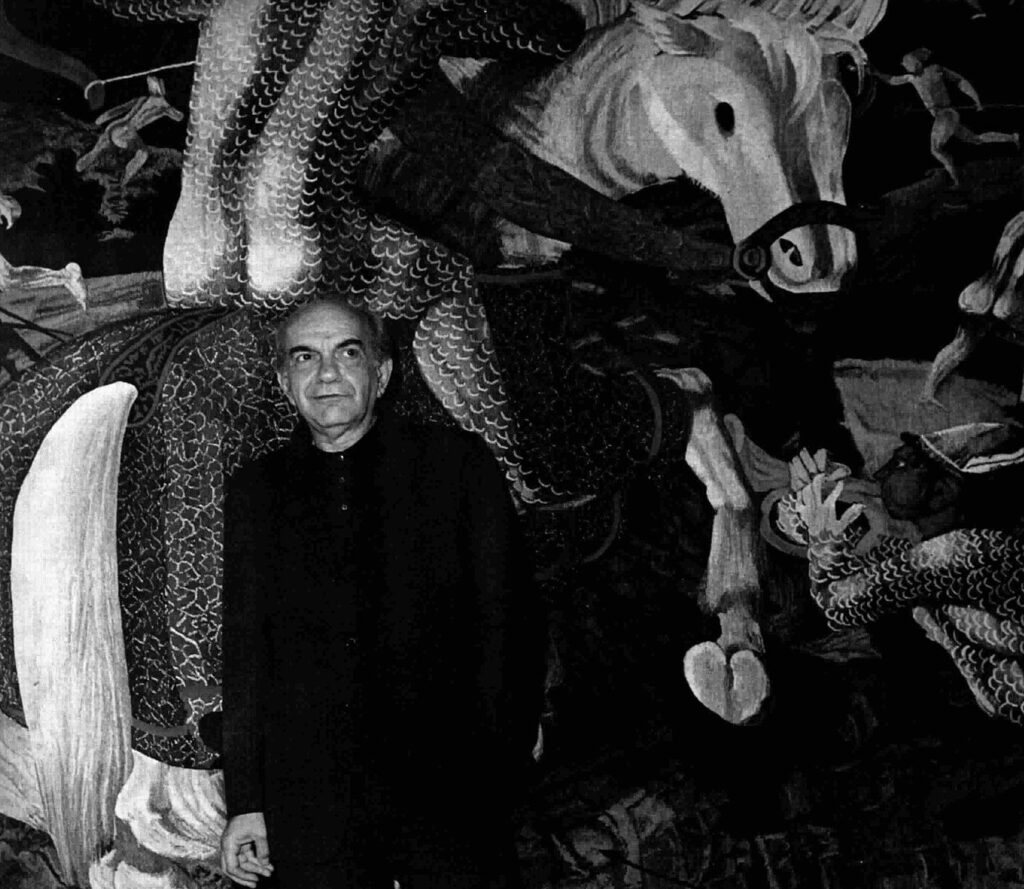

Corrado Cagli, an Expressionist innovator turned refugee from Mussolini, returned to Europe to storm Normandy on D-Day and liberate Buchenwald.

‘Transatlantic Bridges: Corrado Cagli, 1938-1948‘

October 12, 2023—January 27, 2024

Center for Modern Italian Art, 421 Broome Street, Fourth Floor

The Center for Modern Italian Art is tucked into an airy loft on New York City’s Broome Street, drawing inspiration from SoHo’s chicness and Little Italy’s ancestral homeland. It opens to visitors on Fridays and Saturdays, and reservations are encouraged. Its “Transatlantic Bridges: Corrado Cagli, 1938-1948” is a show that the uptown behemoths would be delighted to host, and will regret that they didn’t. Cagli’s charismatic art is surpassed only by his improbable life.

Born in 1910 to a Jewish Italian family, Cagli was something of a prodigy, notching a solo exhibit at the Gallery of Art of Rome at 22. He was among the nucleus of artists who made up the Scuola Romana, committed to Expressionism at a time of classical revanchism. Cagli wrote that in a primordial dawn all has to be reconsidered. Another member of the group, Roberto Longhi, called for an “eccentric and arachnoid art.”

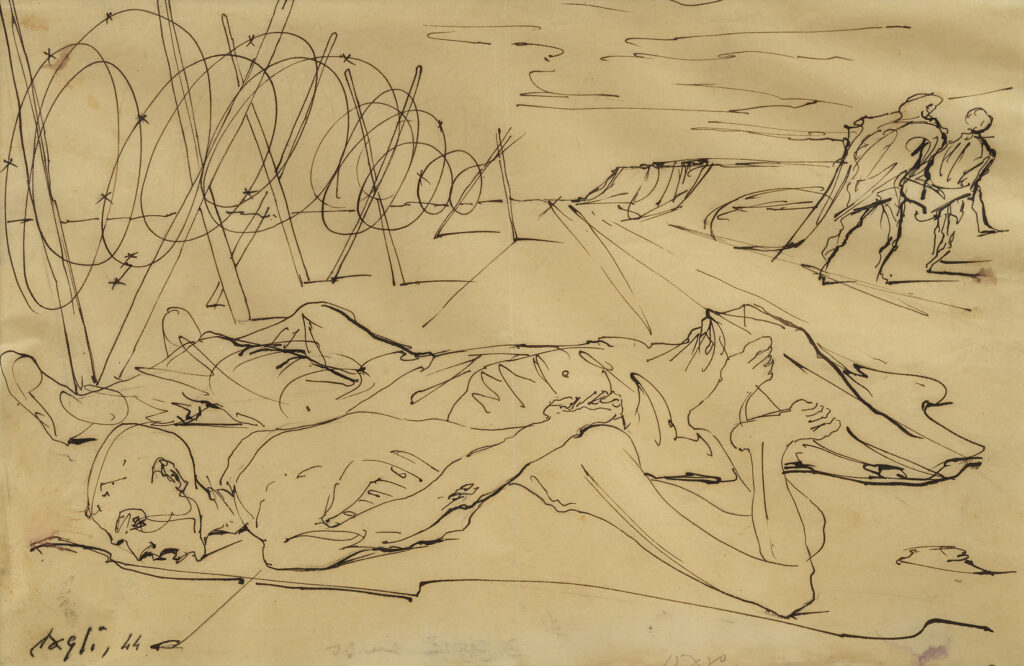

Hopeful revolutionary days would end in 1938, when Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, began in earnest to enforce the program of his senior partner at Berlin. Cagli fled to Paris and then New York. He’d be back in Europe, though, as an enlisted man in the American army, landing at Normandy and fighting across a swath of Germany and Belgium. He was among the forces that liberated Buchenwald, an experience he would commit to paper.

The show, curated by Raffaele Bedarida, covers work Cagli made in America during a decade when his homeland succumbed to fascism. Cagli initially supported Mussolini, only for the fascists to turn against him for both his Jewishness and his gayness. Cagli would alchemize both of those identities into an art that is palpably Jewish and thrummingly erotic. He returned to Italy in 1948, and lived there for the rest of his life.

The exhibit unfolds across just a few rooms, but it gathers a riveting body of work. One showstopper is “Card Game,” first seen at New York in 1937 and now in private hands. Indebted to Cezanne’s series “The Card Players,” Cagli’s riff is suggestive and conspiratorial, the players watching their hands and one another. Beautiful bodies telegraph that the game could be adjacent to sex, and that this isn’t the first time this group has convened.

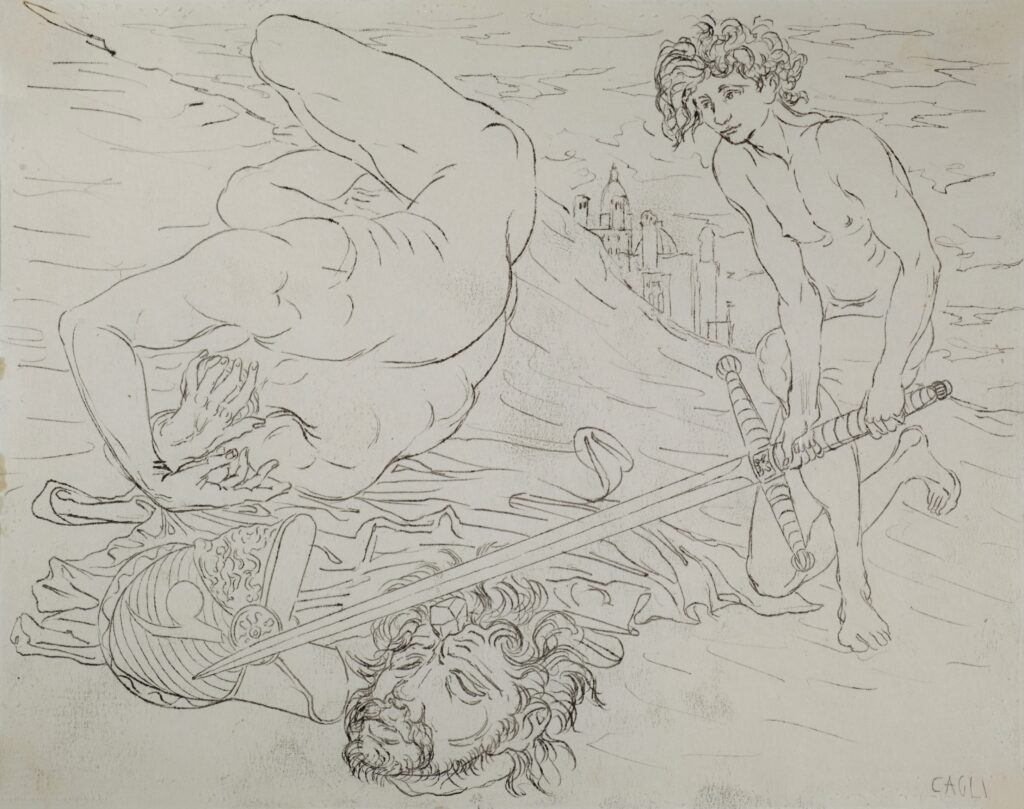

A more serious confrontation is captured in “David and Goliath,” where the lithe shepherd, naked and possessed of unruly hair, pouting lips, and a longsword, has just sliced the Philistine giant’s head from his body. Goliath is seen from the back, the muscles in his shoulders and back rhyming with the sloping hill on which the duel has just taken place. Cagli’s summoning of the sensual charges the scenario with a sense of stakes that reanimates the tale.

“The Neophytes,” executed with encaustic tempera, appears to indicate that Cagli had been thinking of Picasso. The three flesh-covered figures set against a pool and a red-dust landscape echo the Spanish master’s “Three Women at the Spring,” from 13 years earlier. Here, though, the figures are men, glimpsed from behind. Their long bodies are accentuated by the painting’s foreshortened construction, telegraphing the work’s focus.

Cagli’s interest in the body — its angles, features, and flexes — finds more gruesome expression in “Buchenwald,” an eyewitness drawing. Courtesy of just a few lines of ink, we are in the surreal hellscape that GIs encountered when they entered the camp, which Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower would visit. A tangle of emaciated corpses, unnaturally bent, are splayed across the foreground, with barbed wire marking off the left hashmark.

©2023 Dario Lasagni. Via Center for Modern Italian Art

A decade before Cagli entered Buchenwald, he prepared a study for a Zodiac fountain built at Terni. It is a gorgeous retelling of the celestial cast. Men, women, and animals all stride across the stars. They recall similar arrays at ancient synagogues that dot the Galilee. The original mosaic was damaged by bombing, but Cagli himself returned in 1961 to supervise its reconstruction. He insisted, though, that the glass tesserae be replaced with stone ones.