Why I’m Skipping My 50th Reunion at Middlebury College

I’ll miss seeing my classmates and reminiscing about our college days. My regret would be greater, however, if I were to pretend that I was happy with cancel culture at my alma mater.

A half-century ago this month I graduated from Middlebury College. I will not be attending my 50th Reunion.

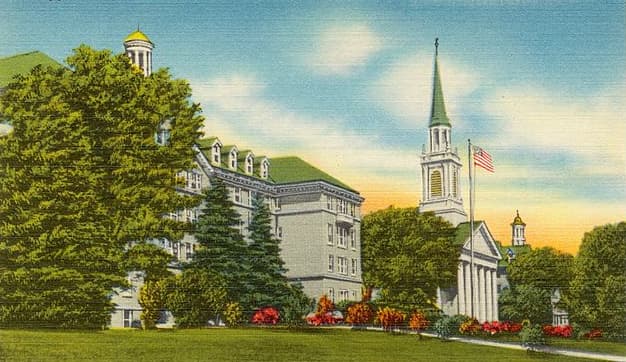

At the crack of dawn seven months ago, while the campus was just coming to life, Middlebury College removed the sign denoting the name of the institution’s house of worship.

It had been Mead Memorial Chapel for more than a century, since a former Vermont governor, John Mead, donated the funds to construct it on the grounds of his — and my — alma mater. He specified its name, to which the trustees readily agreed.

There was no warning that the name would be removed, no public discussion, no hint that such a defenestration was to occur. Instead, the College issued a statement shortly after the deed was done. I thought it was misleading and insulting, and seven months later I’m still hoping that a way will be found to restore Governor Mead’s name to the chapel.

The basis for this furtive removal of Mead’s name was the Governor’s support, in his Farewell Address of 1912, for proposals to restrict the issuance of marriage licenses to those of limited intellectual capacity and to appoint a commission to study the use of vasectomy as a more humane process of sterilization.

The former was passed by the legislature after he left office, but vetoed by his successor. Nonetheless, Governor Mead was proclaimed a eugenicist and the College implied, without evidence, that he was motivated by racism.

The cancellation of Governor Mead contradicts the very purpose of the College. A higher education institution exists for the pursuit of truth and knowledge. That requires a generous exposure to varied ideas and ideologies. Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe observed: “If you only hear one side of the story, you have no understanding at all.”

Middlebury’s denigration of Governor Mead sullies the reputation of a decent man, as well as a generous benefactor. The September 27 statement portrays him as essentially a precursor of Hitler, rather than presenting him in the context of his time. Support for eugenics was mainstream in the early 20th century, embraced by leaders in society, education and government, including, most likely, the Trustees who gratefully accepted his gift.

Presidents, prime ministers, judges, scientists, authors, even the founder of Planned Parenthood supported it. Importantly, the bulk of eugenics activity in Vermont occurred in the 1920s and 1930s, after the Governor’s death.

The College vastly overstates Governor Mead’s role in this matter; he didn’t actually do anything, but merely expressed an opinion. That’s what should trouble every fair-minded observer of this episode: Middlebury is regulating thought, precisely the opposite of what a liberal arts college should do.

John Mead not only served his state with distinction; he and a group of classmates interrupted their studies to join the Union Army. He appeared in arms at Gettysburg and subsequently returned to complete his degree. He practiced medicine for a while, but his prosperity derived from several manufacturing firms that created prosperity for many families. He was a Middlebury trustee, received an honorary degree, and gave generously to our alma mater, beyond financing the Chapel.

Mead was viewed as a progressive. He supported women’s suffrage, toughened child labor laws, strengthened campaign finance statutes, and established Vermont Technical College. He doubled funding for highways and favored clean energy, urging the substitution of hydroelectric power for coal. He was seriously considered for the vice-presidential nomination on the national ticket in 1912.

Vermont’s native son, Calvin Coolidge, observed that “Education is to teach men not what to think but how to think.” That requires hearing different ideas and acknowledging them in context. It means learning from history, not erasing it.

The College bases its decision on inconsistency with its values. On the contrary, purging the legacy of someone who revered our alma mater and gave generously to support it, due to a single remark that we a century later deem unacceptable, hardly conforms to the purpose of the academy.

Nearly everyone’s legacy is mixed. I’ll bet all of us have at some point made a remark or written a comment that, upon reflection, seems inappropriate, even offensive, and that we later regret. Is that the sole basis on which a long and distinguished career should be judged? Under the scrutiny of the Thought Police, no one’s legacy is safe.

Yale Professor Anthony Kronman, in his book “The Assault on American Excellence,” urges against erasure of history. Rather, he writes, we should “contextualize” it. That’s what Middlebury ought to do, not purge the good name of a beloved and generous alumnus.

I’ll miss seeing my classmates and reminiscing about our college days. My regret would be greater, however, if I were to pretend that I was happy to be there, in the shadow of Mead Chapel, the scene of the College’s expunction of the Governor’s legacy.

I hope that the institution’s officials reconsider this unfortunate deed. Cancel culture is alive and well at Middlebury, so, for now, I’ll celebrate alone.