Celebrating Two Heroes of the Cold War Who Freed Millions From Communism

Thomas Donahue and Morris Amitay set a strategy for foreign affairs to be studied for generations.

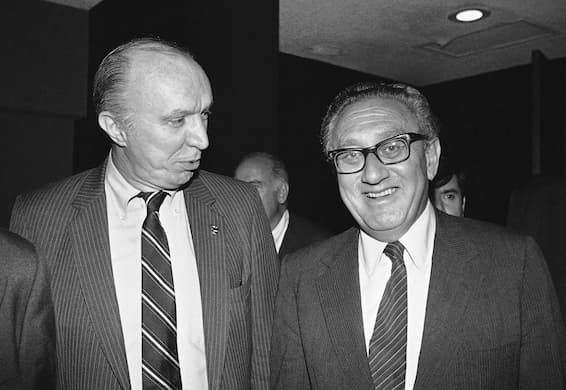

This month saw the loss of two giant figures in the struggle for freedom and democracy — Thomas Donahue and Morris Amitay. They are worth pausing to remember because their lives offer examples of careers devoted to just causes. The future of America and of freedom in the world depends on whether America is able to produce more heroes in their mold.

Donahue and Amitay are particularly newsworthy because they represented what, these days, can frequently look like a rare species — Democrats who favor an active, engaged foreign policy that strongly supports freedom and democracy worldwide.

It’s not overstating it to say that Tom Donahue was an architect of our victory in the Cold War. He was secretary-treasurer of the AFL-CIO between 1979 and 1995. Together with a small group of likeminded labor leaders — Albert Shanker, Tom Kahn, Irving Brown, Lane Kirkland, Adrian Karatnycky, Eric Chenoweth, Irena Lasota — he backed Solidarity in Poland. That free trade-union movement led by Lech Walesa ultimately threw off communist rule.

There were other factors, of course — President Reagan’s moral clarity and military buildup, Pope John Paul II, the Soviet Jewry movement and its heroes like Natan and Avital Sharansky and Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, Soviet human rights activists like Andrei Sakharov, not to mention communism’s own inherent flaws and contradictions.

Without brave American risk-takers like Donahue, though, the Soviet Union might have lasted decades longer than it did, and hundreds of millions of individuals trapped behind the Iron Curtain would have been deprived of basic freedoms for many more years.

Donahue’s role in defeating Soviet communism — even the role of American labor overall — hasn’t ever really been properly told. The left-wing press in America has mostly emphasized an alternative narrative that blames Kirkland and Donahue for the decline of the labor movement in the United States, and that attributes the fall of communism to the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev.

That’s nonsense: Gorbachev had no intention of voluntarily dismantling communist rule. The decline of the American labor movement has had to do with other factors, such as the outsourcing of manufacturing jobs to China, where Communist Party rule to this day bans independent labor unions and many other freedoms.

Donahue’s personal story, recounted in a Library of Congress oral history interview, is classically American in its trajectory of upward mobility. His father was a deckhand on the Staten Island ferry. Donahue himself worked for two years as an elevator operator at the Best & Company department store. He went to law school at night and earned a degree from Fordham.

The support Donahue and the AFL-CIO rendered to Solidarity was concrete. A 2007 article by Gregory Domber in the Polish Review traces it in dollars and cents — thousands of dollars for shortwave radios, mimeograph machines, a printing press, all documented in AFL-CIO records, largely memos to Donahue from Kahn. The AFL-CIO at the time had a more hawkish position on Poland than the Reagan administration and its allies did; there was a debate in March 1981 between Tom Kahn of the AFL-CIO and Norman Podhoretz, with Kahn arguing for a tougher financial line against the Polish communist regime.

Morris Amitay, like Donahue, was a New York City kid who eventually made his way to Washington. He worked as an aide to Senator Ribicoff, a Democrat of Connecticut. Amitay was executive director of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee between 1974 and 1980, according to an obituary in the Jewish News Syndicate.

The obituary describes Amitay going to a White House meeting to advance the Jackson-Vanik amendment, which linked American trade relations with the Soviet Union to freedom of emigration. The same obituary reports that on July 25, 1977, “an attacker set off 60 pounds of dynamite outside Amitay’s house; the ensuing explosion killed the family dog.”

The Congressional Record of December 13, 1974, carries remarks by Senators Jackson and Ribicoff celebrating the imminent passage of the Jackson-Vanik amendment. Said Jackson: “In all candor, it was the able staff of the three senators, who did the job. They were led largely by Richard Perle, of my staff, but Morris Amitay, of Senator Ribicoff’s staff, and Mr. Lakeland, of Senator Javits’ staff, and he, all worked together as a team.”

Reagan, in a July 18, 1975, newspaper column, noted the effect: “Remember how they stepped up approvals of immigration of Russian Jews from the Soviet Union about the time the trade bill was being debated?”

All of those who were once trapped behind the Iron Curtain and are now free owe Donahue and Amitay thanks. As for those in Iran and China and Afghanistan who remain subject to tyranny, they await Americans who will learn from Donahue’s and Amitay’s successes and who will replicate them in the 21st century.