Trump’s Enemies Cite a Confederate Rebel, Jefferson Davis, as Reason He Should Be Legally Barred From the Presidency

A liberal legal watchdog argues that Trump ‘disqualified himself from holding public office ever again’ in pursuit of a ‘desperate and unlawful effort to cling to power.’

The filing of an appellate brief, by an activist ethics outfit known as the Center for Responsibility and Ethics at Washington, seeking to bar President Trump from the ballot in Colorado escalates the legal battle over whether the Constitution’s Framers contemplated political life after insurrection.

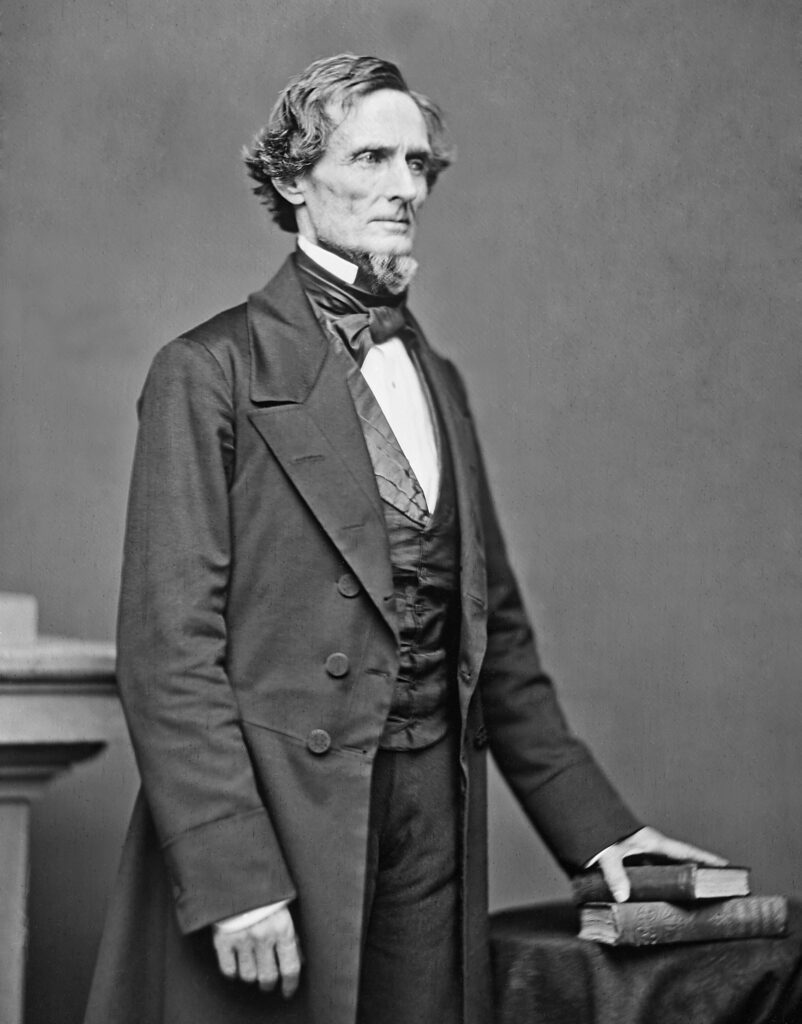

At the heart of CREW’s case is an analogy between Mr. Trump and the sole president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis. The commander in chief of the rebels, Davis was captured, accused of treason, and imprisoned after the South’s defeat in 1865. He was released without trial two years later.

The appeal of the self-described watchdog organization asks the Colorado supreme court to rule that Section Three of the 14th Amendment, which bars from office those who previously took an oath to the Constitution and then “engaged in insurrection or rebellion,” applies to Mr. Trump. It maintains that he “disqualified himself from holding public office ever again” in pursuit of a “desperate and unlawful effort to cling to power.”

The pro-disqualification faction lost that argument at the district court level, albeit in a fashion that appears to have whetted its appetite for appeal. Judge Sarah Wallace ruled that what happened on January 6 was an insurrection — she found that the “events on and around January 6, 2021, easily satisfy” the definition of “insurrection” — and that Mr. Trump “engaged” in those events.

Judge Wallace, though, found that the 14th Amendment’s applicability to, among other officials, an “officer of the United States” excludes the presidency, which is otherwise uncovered by the section’s terms, from the ambit of disqualification. She is “unpersuaded that the drafters intended to include the highest office in the Country in the catchall phrase ‘office … under the United States.’”

Judge Wallace notes that CREW’s effort to “lump the Presidency in with any other civil or military office is odd indeed and very troubling,” because of the office’s responsibility for the entirety of the executive branch. Article II empowers the president to appoint “Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for.” Is he, though, such an officer?

“There is scant direct evidence,” according to Judge Wallace, “regarding whether the Presidency is one of the positions subject to disqualification.” CREW, though, argues that “insurrectionists running for President” are barred from the ballot because the “natural meaning of ‘officer of the United States’ is anyone who holds a federal ‘office.’” The appeal calls this “common sense.”

The group argues that the “Framers did not intend” to prohibit “insurrectionists from holding every federal or state office except for the highest and most powerful in the land.” Of greater salience, though, could be the intention of what historian Eric Foner calls the “Second Founding,” the suite of amendments — 13th, 14th, and 15th — passed in the years after the Civil War.

That is where Davis comes in. Before the war, the Mississipian was a lieutenant in the United States Army, a congressman, a senator, and then America’s secretary of war. He served as president of the Confederate States of America. After the Union victory, he was accused of treason and imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Virginia.

Two years later, though, he was released without trial after President Andrew Johnson’s Cabinet could not devise a way to try him without risking acquittal. Johnson pardoned Davis on Christmas Day, 1868. The Confederacy’s former president went on to run an insurance company in Tennessee.

Mr. Trump was impeached on one count, incitement to insurrection, and was discovered to be “not guilty” by the Senate. He has never been criminally charged with insurrection, nor has anyone else involved in the events of January 6. Judge Wallace and another state court judge, in New Mexico, are the only jurists to have ruled that one occurred.

One legal sage, Gerard Magliocca, testified to Judge Wallace as to “the consensus at the time that Jefferson Davis was ineligible to be President” because of his stint as an insurrectionist leader. He explains that “it would have been odd to say that people who had broken their oath to the Constitution by engaging in insurrection were ineligible to every office in the land except the highest one.”

It appears as if Davis was on the minds of Americans as they debated ratification of the 14th Amendment. In 1867, the Gallipolis Journal, based in Ohio, noted that rejecting the amendment would “render Jefferson Davis eligible to the Presidency of the United States,” a possibility that those scribes found “revolting.”

That same year, the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, in an article under the headline, “Shall We Have a Southern Ireland?” observed that “Jefferson Davis, unless by some miracle of justice he should first expiate his atrocious crimes upon the gallows,” would be disqualified unless he was relieved of disqualification by a two-thirds vote of Congress, as allowed for by Section Three.

CREW notes that as Reconstruction gave way to reconciliation, Davis was once again at the center of the debate over amnesty. The 1872 Amnesty Act, signed into law by President Grant, excluded high Confederate officials like Davis. A report from the proceedings notes that the possibility that the notion of an amnesty that left Davis politically viable elicited laughter in Congress.

Now, the precedent of America’s signature anti-heroes could determine whether the nation’s 45th president is allowed to compete for votes in Colorado and elsewhere. The Colorado supreme court, and potentially, the United States high court, are now tasked with deciding whether the effort to ban Mr. Trump is, constitutionally speaking, a lost cause.

________

This article has been updated from the bulldog.