Trump, as Alaskans Balk, Puts McKinley, a Unifying Figure, Back on His Mountaintop

The move, the 47th president says, will ‘restore the name of a great president’ to ‘Mount McKinley, where it should be and where it belongs.’

President Trump is restoring President McKinley’s name to the tallest peak in North America, drawing objections from Alaskans. The state’s two GOP senators prefer, in Denali, one of several local names, but Trump’s executive order respects only a compromise President Carter struck in 1980.

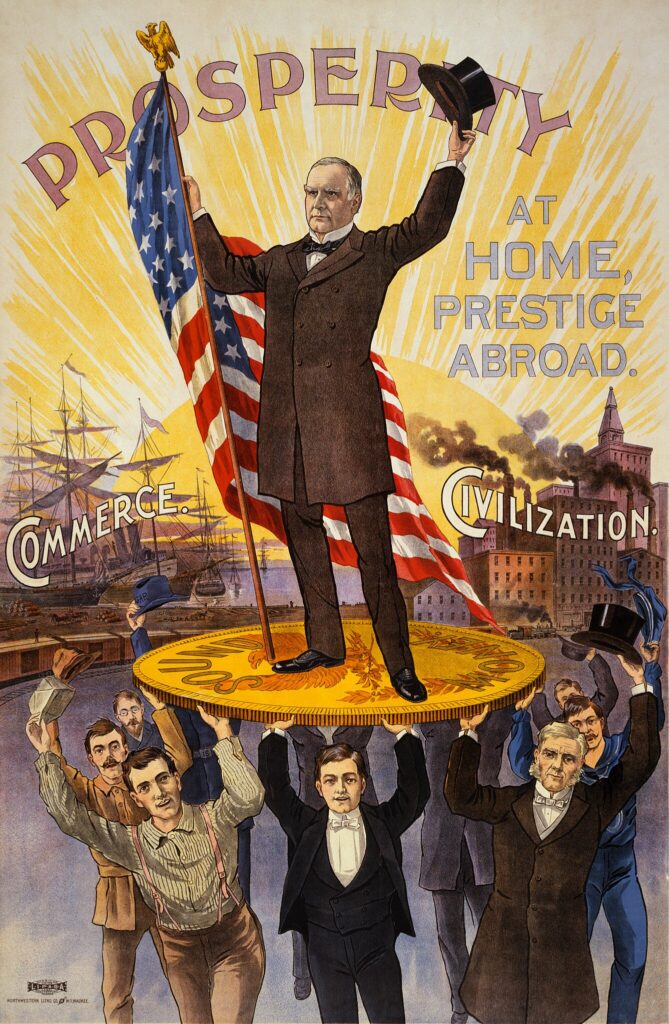

In his inaugural address on Monday, Trump pledged to “restore the name of a great president, William McKinley, to Mount McKinley, where it should be and where it belongs.” The 45th and 47th president has come to admire the 25th, claiming him as a mentor on tariffs.

On January 24, 1897, William Dickey christened the 30,000-foot summit in The New York Sun. He wrote that his men had “named our great peak” for McKinley after receiving news that the Ohio governor had secured the Republican presidential nomination.

McKinley has gained increasing stature over the years. He signed, among other things, the Gold Standard Act of 1900. McKinley was assassinated in 1901 and the mountain bearing his name, which he was never able to visit, became a memorial to his greatness. America made the name official in 1917.

As this columnist wrote in October, “It would not be too much to suggest that the Sun named the mountain.” However, in the century that followed, Alaskans chafed under the designation, preferring Denali. President Obama acceded to their wishes in 2015, wiping McKinley off the map.

“President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs,” Trump said, “and through talent. He was a natural businessman.” It’s clear that in the new president’s binary scale — losers and winners — he judges the martyred McKinley as one of the latter.

“I strongly disagree with the president’s decision on Denali,” Senator Murkowski of Alaska wrote on X after Trump’s address. She noted that the mountain had been “called Denali for thousands of years by … Koyukon Athabascans.”

An aide for Senator Sullivan, Amada Coyne, told the Anchorage Daily News last month that the lawmaker, “like many Alaskans, prefers the name” Denali. His wife, Julie Fate, is an Athabascan whose mother was co-chair of the Alaska Federation of Natives.

Congressman Nicholas Begich, Alaska’s at-large House member, was more open to Trump’s restoration. “I’m focused on job-creation opportunities in Alaska,” he told reporters while leaving the inauguration, and what the mountain was called “is of little concern to me.”

According to the National Park Service “no fewer than nine native groups,” have names for the mountain, including one for each of “five Athabascan languages.” Mr. Obama settled on Denali, not so much a name as a description, meaning “the tall one” or “the great one.”

In 1980, President Carter had struck a balance between Alaskans and McKinley’s boosters in Ohio, signing the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. It renamed McKinley National Park Denali National Park and Preserve while leaving the former president’s name on the granite pile.

A unifying figure, McKinley is an odd flashpoint for acrimony between a Republican president and members of Congress. The last president to serve in the Civil War, he won 28 of the 45 states with a margin of victory in the popular vote of 7.1 percentage points.

McKinley’s prosecution of the war against Spain, featuring Buffalo Soldiers and a former Confederate officer commanding in Cuba, helped heal many divisions. On domestic policy, in his first two years, McKinley appointed more Blacks to federal office than any of his predecessors.

An indication of how McKinley felt about personal accolades is found in his rejection of the Congressional Medal of Honor. At the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest day in American history, he rode under heavy fire to deliver provisions to Union soldiers. A monument marks the spot of his heroism.

As McKinley’s campaign for president heated up in 1896, his supporters appealed to President Cleveland, a Democrat, to award their man the nation’s highest military honor. The major general commanding the Army agreed, until McKinley asked that the idea be shelved.

The author of “President McKinley: Architect of the American Century,” Robert W. Merry, weighed in when I interviewed him after Mr. Obama’s order. “I didn’t get too concerned about it,” he said, “and I don’t think McKinley would have cared very much about it one way or another.”

On tariffs and topography, Trump has put a reluctant American hero back on top. McKinley belongs to all Americans, whatever state, tribe, or faction they belong to or language they speak. Alaskans may require convincing, but McKinley is again offering his service to heal the nation’s continental divides.