‘The Heart and Lungs of Liberty’

The Supreme Court curbs the SEC’s long campaign to evade the Seventh Amendment right of trial by jury.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jarkesy is a victory for the plain language and logic of the Constitution. It holds that “when the SEC seeks civil penalties against a defendant for securities fraud, the Seventh Amendment entitles the defendant to a jury trial.” It is also, legal sage Philip Hamburger tells us, “the beginning of the end of the administrative state.” He celebrates the ruling as a “huge victory for jury rights.”

The Seventh Amendment ordains that “in Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars,* the right of trial by jury shall be preserved.” The question in Jarkesy was whether the kind of enforcement undertaken by the SEC is properly understood as occurring “at common law.” Chief Justice Roberts, writing on behalf of the court’s six conservatives, defends the “right to be tried by a jury.”

A hedge fund manager, George Jarkesy, was accused of misleading investors. The SEC moved against him in their own tribunals, and he was found liable by a judge whose check is cut by the agency trying him. Mr. Jarkesy and his company were fined $300,000 and forced to disgorge a further $685,000 in what the SEC deemed to be illicit gains. Riders of the Fifth United States Appeals Circuit sided with Mr. Jarkesy. The SEC appealed, and lost.

The riders of the Fifth Circuit found for Mr. Jarkesy because of “three independent constitutional defects” in the proceedings he had been accorded. In addition to determining that he was entitled to a jury trial, they also found that “Congress unconstitutionally delegated legislative power to the SEC” and that the restrictions on removing the agency’s judges amounted to an unconstitutional affront to presidential power. It was a body blow in triplicate.

The high court declined to go as far as the bold riders of the Fifth Circuit. The Nine addressed only the jury question. More than 40 years ago, the Nine decided that if a case turns on the “stuff of the traditional actions at common law tried by the courts at Westminster in 1789,” a jury is required. The court’s liberal dissenters invoke the government’s right to claim civil penalties without trial as an “injured sovereign.”

Mr. Hamburger, though, tells us that the high court’s stand for constitutional process is a “profoundly important step in stopping the administrative onslaught against our civil liberties.” We’ve called the SEC one of the “building blocks of FDR’s attempt to bring America’s economy under the thumb of the bureaucrats at the Columbia District.” It was the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 that allowed the SEC to funnel cases to its own courts.

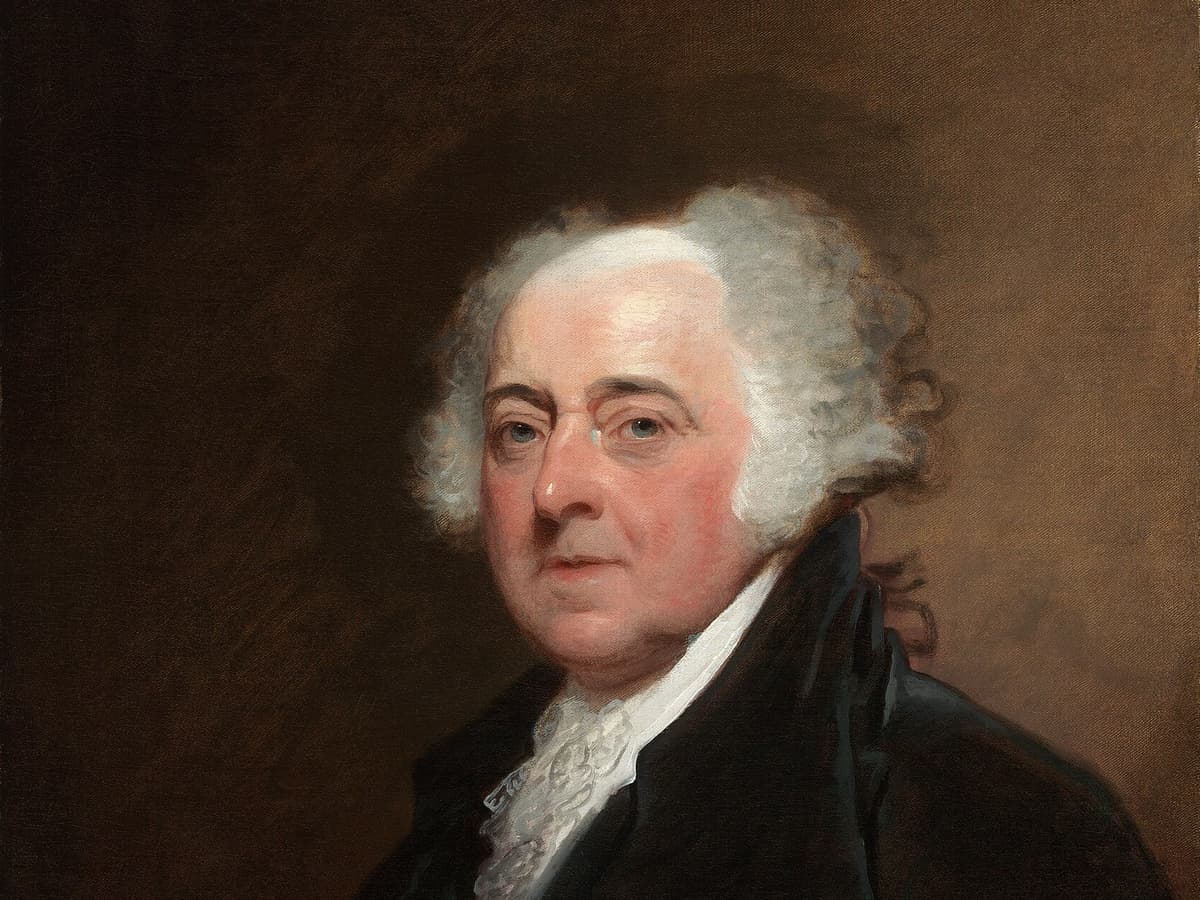

Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas, in a well-wrought concurrence, observe that the Kafkaesque alleyways of administrative justice resemble the reviled vice-admiralty courts of colonial times. Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to Thomas Paine, called juries “the only anchor, ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution.” John Adams called them “the heart and lungs of liberty.”

While Jarkesy is worth celebrating, the record of the administrative state hangs in the balance. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has already fought off a challenge to its funding mechanism. The high court has yet to rule on two cases that challenge the doctrine of Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, which grants agencies deference. Yet this court could still secure the honor of being dubbed what these columns have called the Hamburger Court.

________

* Heads up, your honors: This is the only surviving use in the Constitution of the word “dollars.” The Framers knew exactly what they meant by it — 416 grains of standard silver or 371 1/4 grains of pure silver, or the equivalent thereof in gold.