The Day U.S. Grant Was Stopped for Speeding

Hold your constitutional horses, we say, until the Supreme Court reconsiders the question of presidential immunity for unofficial acts.

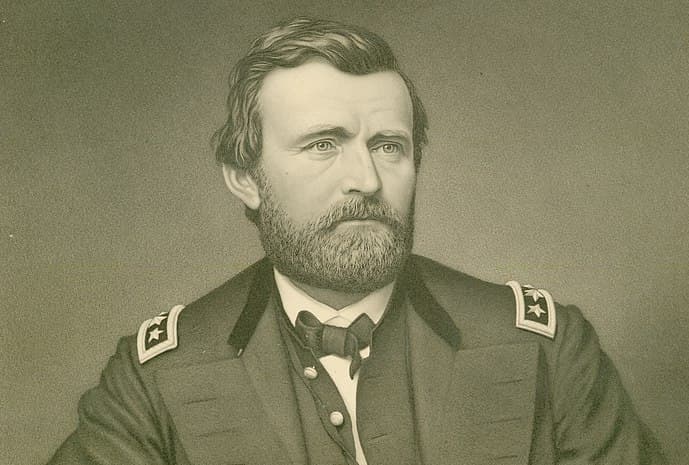

While waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on presidential immunity, let’s turn to President Grant and his horse and carriage. In 1872, Grant, then the 18th president, was, as the story goes, pulled over for speeding. The police officer, William Henry West, recalled that Grant resembled “a schoolboy who had been caught in a guilty act by his teacher.” Grant expressed his admiration for West, who’d appeared in arms in the war. West arrested him anyhow.

If true, it marks the only time in history that a sitting president was arrested. In 2012, the head of the Metropolitan Police confirmed that Grant was “actually stopped and cited.” Now that long-ago joyride — not official business — could find its way into a Supreme Court ruling marking the bounds of presidential immunity. Any day now, the high court will hand down its decision on what protections President Trump — and all presidents — are owed.

The memory of Grant’s carriage sallied into the Supreme Court during oral arguments in Trump v. United States. It was Trump’s attorney, John Sauer, who invoked “Unconditional Surrender.” Mr. Sauer told Justice Neil Gorsuch that since “President Grant’s carriage-riding incident, everyone has understood that the president could be prosecuted at least for things like private conduct.” That’s quite a concession, given that he was hired to champion immunity.

Justice Gorsuch quickly seized on Mr. Sauer’s yielding with respect to private acts, asking the lawyer if he agreed that “the president can be prosecuted after he leaves office for his private conduct.” Mr. Sauer declared “We agree with that.” With that admissions in hand, Justice Gorsuch explained that the case now reduces to “how to segregate private from official conduct that may or may not enjoy some immunity.” Hold the constitutional horses, we say.

This could be a golden opportunity for the Supreme Court to reconsider its reluctance to extend immunity to private presidential acts. A unanimous court, in Clinton v. Jones, asserted that they have “never suggested that the President, or any other official, has an immunity that extends beyond the scope of any action taken in an official capacity.” They add that there is “no support for an immunity for unofficial conduct.”

The Clinton court cited an earlier decision, Nixon v. Fitzgerald, to explain that the justification for attaching immunity to official acts is to encourage the president against being “unduly cautious in the discharge of his official duties.” President Jefferson worried that excessive suits could be used to bandy a president “from pillar to post, keep him constantly trudging from north to south & east to west, and withdraw him entirely from his constitutional duties.”

Such badgering is no less distracting if it attaches to private acts or official ones. The outcome is the same — the withdrawal from constitutional action that so worried Jefferson. As Justice Amy Coney Barrett noted to the government’s lawyer, Michael Dreeben, much of Special Counsel Jack Smith’s January 6 indictment of Trump rests on acts even Mr. Sauer concedes are “private.” How much insulation, then, does immunity really offer?

The justices did appear concerned that the trials of Trump could herald a new age of presidential prosecutions. This is not to suggest the justices condone criminality. A challenge for the courts, though, is where to draw the line between private and public acts. As Chief Justice Roberts asked during oral arguments, if “the official act is appointing ambassadors,” what is the way to analyze a case in which the president names an envoy “but it’s in exchange for a bribe”?

Plus, whether or not Grant was arrested for speeding — there are grounds for doubting the tale — the prospect of any local police officer arresting the commander-in-chief on a criminal charge could well give the justices pause. The same question applies to a criminal indictment by any local district attorney — perhaps even one with a partisan bias. There’s a reason why the Framers left the question of policing presidential misconduct to the process of impeachment.