Taking Down Statues of Famous Namesakes Doesn’t Make History Go Away

A Washington and Lee alumna – and Pennsylvania native – wonders if erasing the statues of Robert E. Lee and William Penn seeks to hide problems rather than solve them.

The past year has seen the removal or destruction of many historically significant memorials, all in the name of inclusion and the expiation of the sin that will forever stain our nation — slavery.

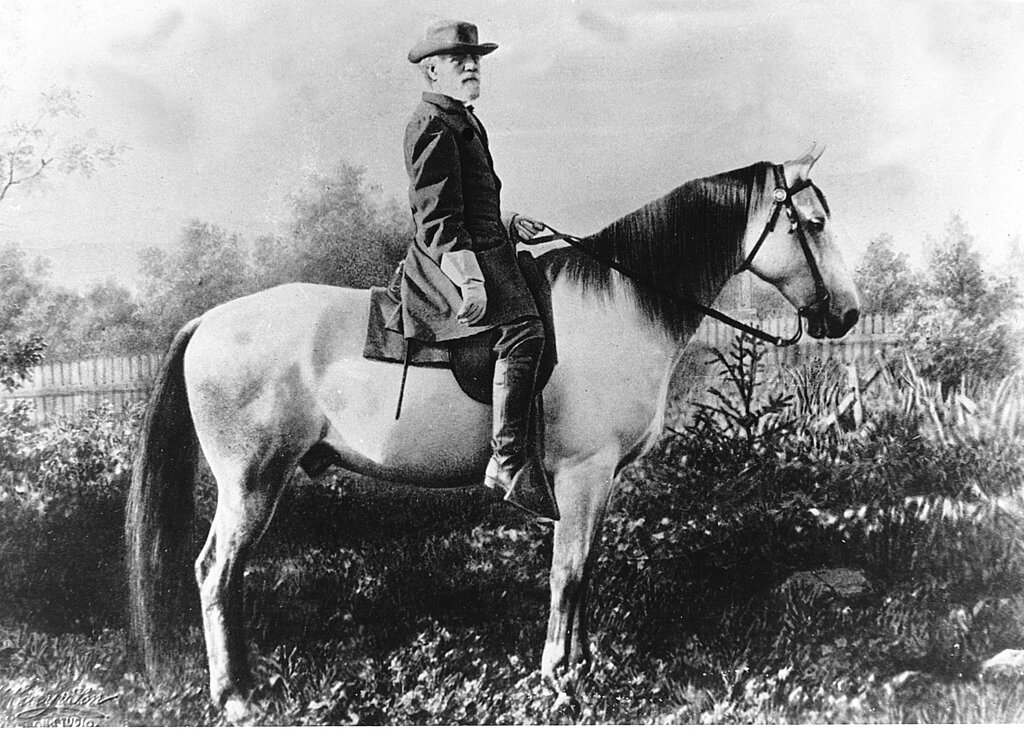

In 2021, Charlottesville, Virginia, took down its statue of the top commander of the Confederate forces, General Robert E. Lee. It was destroyed and melted two years later. Then in December, the Confederate memorial at Arlington National Cemetery was removed, headed for an obscure state park two hours away. Most recently, the National Park Service sought to remove a statue of Pennsylvania’s namesake, William Penn, in its efforts to make the park where it stood “more inclusive.”

Penn died 147 years before the outbreak of the Civil War. However, he couldn’t escape being tarred by liberals’ misunderstanding of his relationship with Native Americans and turned into a symbol of the evils of colonialism. Online indignation from local officials granted Penn’s statue a stay of execution, but the Park Service website still states that the proposed changes would provide “a more welcoming, accurate, and inclusive experience for visitors” and that “the Penn statue … will be removed and not reinstalled.”

Just like our own lives, a nation has a story to tell. Tearing down historical monuments doesn’t change the story. It simply removes the dark parts of the story, and like any good therapist will attest, one can’t erase one’s past. One must confront it to heal and move forward.

I am certainly no fan of slavery. Nor am I some Confederate flag-flying Southern belle. I am from Pennsylvania. The most recent suggestion that my state’s namesake be removed from Philadelphia was the last straw for me. The first straw was the removal — and subsequent destruction — of Robert E. Lee.

Lee happens to be a namesake of my alma mater, Washington and Lee University, situated at Lexington, Virginia. The erasure of his memory came on the heels of persistent attacks on the educational institution that I called home for four years.

Last summer, a plaque commemorating Traveller, Lee’s horse during and after the Civil War, was quietly removed from his stable on campus earlier this summer.

The metal melting of Traveller’s owner followed a yearlong campaign in 2021 to force my alma mater to change its name. Lee’s name was added in 1870 to the name of the original Washington College (named after our first president), after the retired general had served as its president for five years right after the Civil War. During his tenure, he transformed and elevated the university.

Civil war memorials, and certainly Lee’s, do not fill me with warm fuzzies. I was at the forefront of co-education on campus (it had been all-male until 1985). There were several professors who would have preferred women weren’t in their classrooms and they had no problem letting us know, either through deflated grades or misogynistic comments.

That attitude permeated the culture of the campus. There were 16 fraternities and four sororities and almost the entire student body was involved in Greek life. This didn’t exactly promote diversity of thought or elevate women. I experienced several instances of trauma in my four years at Washington & Lee with ramifications I’m still learning to overcome.

People change and systems change and despite some unhappy memories, remnants of the “Old South” also remind me of the beauty of the campus’ historic Colonnade and the professors who took time to mentor and guide me. I still feel immediate camaraderie when I meet someone else who graduated from W&L because it was such an intimate, small community.

Yet Lee, who was President Lincoln’s first choice to lead the North, was also a man of great civility and honor. One of the most unique and exceptional traditions of W&L is its honor system, a commitment to self-governance endorsed by Lee. It makes the students, not faculty, responsible for the rule of law on campus and the justice administered when that law is broken.

“As a general principle you should not force young men to do their duty,” Lee said, “but let them do it voluntarily and thereby develop their characters.” My oh my, how far students all across the country have fallen from this charge. An institution can only go so far in promoting honor, integrity, and civility. It needs students who value and embrace those virtues.

Removing and destroying Lee’s likeness will not change history or eradicate the stain of slavery. It may, however, remove the reminder that we all struggle with the line between good and evil that runs straight through the center of every man’s heart, and the grace needed for forgiveness.

Lee was more than just the Confederates’ supreme commander. He was a great benefactor and leader and he himself struggled with his legacy. Late in life, he said he didn’t want his time as a Confederate general to solely define him.

In an 1865 letter to his wife, Lee wrote that, “Life is indeed gliding away and I have nothing good to show for mine that is past. I pray I may be spared to accomplish something for the benefit of mankind and the honor of God.”

The better we’re able to hold our own sins alongside our gifts and goodness, the more integrated and whole we become, both as individuals and as a country.

A column in the Washington Post celebrating the downfall of Lee statue’s said that, “That statue in Charlottesville emboldened racists, prompted public displays of violence and led to private threats — and those don’t melt down as easily as bronze.” I agree, but argue that it wasn’t a statue that emboldened toxic behavior by white supremacists. It was hate, and no amount of melting of statues or removal of plaques can erase hate in a man’s heart. Only God can do that.

“The removal of these statues is not about history, it’s about futures,” the same article claimed. Fair enough. But you can’t have a future if you hate your past. We certainly can be critical of the past, but if we continue to rage against it and attempt to erase it, we’ll forget how we got to the future in the first place, and the lessons we learned along the way.

At least the Arlington memorial has been moved to land owned by the Virginia Military Institute (which actually neighbors the W&L campus, and which in recent years had its own controversy over what to do with a statue of another brilliant Confederate general – and VMI instructor – Stonewall Jackson). Unlike the Arlington memorial, Lee’s statue was not only melted down, it is slated to be transformed into a piece of art that the Charlottesville City Council says will better “reflect the City’s values of inclusivity and racial justice.”

Why do we need to completely destroy something in order to erect something new? Is there not room for both?