Pressure Mounts on Trump To Defend His Signature Legal Victory — Jack Smith’s Disqualification From the Mar-a-Lago Case

The 45th president has until Friday to persuade the 11th Appeals Circuit to preserve Judge Cannon’s ruling.

President Trump has until Friday to persuade the 11th United States Appeals Circuit to uphold Judge Aileen Cannon’s ruling disqualifying Special Counsel Jack Smith from the Mar-a-Lago case.

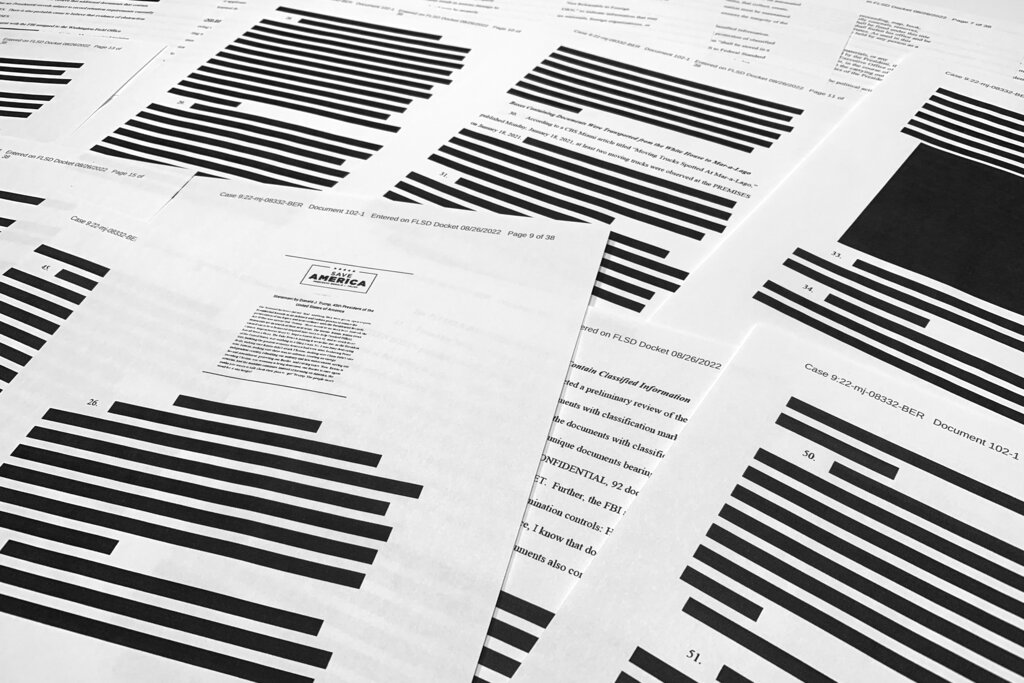

The disqualification of Mr. Smith and the dismissal of charges against Trump for stashing secret documents at his Palm Beach manse amount to the 45th president’s signature legal victories in the four criminal cases against him. They could, though, amount to temporary triumphs if the Florida jurist is reversed.

Judge Cannon’s ruling was a stunning setback for the special counsel, who is tasked by Attorney General Garland with prosecuting Trump for January 6 and the retention of documents. Both cases, unprecedented in American history, have faced skepticism from the bench. The government’s case in Florida, which many saw as sturdier, is now in more dire straits.

The lengthening road to trial came into sharp relief this week when the New York Times reported that two prosecutors, Julie Edelstein and David Raskin, left Mr. Smith’s office. The case is now primarily in the hands of appellate specialists, lawyers skilled at mounting arguments before circuit courts and the Supreme Court.

Any tendency of Trump’s lawyers to err on the side of overconfidence could be mitigated by Judge Cannon’s record. She has been reversed in this case before, most notably when she appointed a special counsel to oversee the collection of the records from Mar-a-Lago. The circuit riders reckoned that her ruling “would be a radical reordering of our case law … and both would violate bedrock separation-of-powers limitations.”

A reversal that resembles that one would return the case to Judge Cannon’s court. A group of legal scholars, among them Laurence Tribe and George Conway, is pushing for a more drastic ruling — one that removes Judge Cannon from the case. Federal law allows for a judge’s removal if she “engaged in conduct that gives rise to the appearance of … a lack of impartiality in the mind of a reasonable member of the public.”

Mr. Smith has demurred from that demand, but the 11th Circuit could explore it even without his endorsement. The riders will turn their attention to Judge Cannon’s determination that General Garland lacked statutory authorization to appoint Mr. Smith, who was not nominated by the president nor confirmed by the Senate. She also found his funding unlawful.

Judge Cannon’s decision declares that Mr. Smith’s “position effectively usurps … important legislative authority … in the process threatening the structural liberty inherent in the separation of powers.” She rejects what she calls Mr. Smith’s “strained statutory arguments, appeals to inconsistent history, or reliance on out-of-circuit authority.” She insists that the “Appointments Clause is a critical constitutional restriction.”

The judge’s boldest determination was that the Supreme Court case of United States v. Nixon, which appeared to endorse the ability of the attorney general to name subordinate prosecutors, “is not controlling, and it should not be extended to today’s context” because the attorney general’s statutory appointment authority “was not raised, argued, disputed, or analyzed.” She discerns that the ruling is dictum, or non-binding.

Now Mr. Smith has asked the 11th Circuit to overrule Judge Cannon’s holding that his appointment “breaches two structural cornerstones of our constitutional scheme — the role of Congress in the appointment of constitutional officers, and the role of Congress in authorizing expenditures by law.”

Mr. Smith’s brief to the 11th Circuit reminded the riders: “Attorneys General appointed outside attorneys to prosecute some of the most significant cases of the day, including the prosecution of Jefferson Davis for treason and the prosecution of John Surratt for aiding and abetting the assassination of President Lincoln.” He notes that special counsels have been appointed since before the Department of Justice existed.

The special counsel tells the circuit that Judge Cannon “deviated from binding Supreme Court precedent, misconstrued the statutes that authorized the Special Counsel’s appointment, and took inadequate account of the longstanding history of Attorney General appointments of special counsels.” He also alleges that her reading of Nixon casts aside “carefully considered, unequivocal language from a unanimous Supreme Court.”

Judge Cannon’s opinion is binding only in the Southern District of Florida — for now. Judge Tanya Chutkan of the District of Columbia has already telegraphed her understanding that the the District of Columbia Circuit of the United States Court of Appeals has already ruled that attorneys general possess the power to appoint subordinate prosecutors.

General Garland, who once sat as chief judge of the District of Columbia Circuit, agrees. He took to television to accuse Judge Cannon of making a “basic mistake about the law” when she disqualified his handpicked special counsel. The issue could soon find a hearing before the high court, where there could be justices eager to review the precedent that granted constitutional imprimatur to independent counsels, the precursors to today’s special counsels.