One Hundred Years After Debs Campaigned From Prison, Trump May End Up Doing the Same

The 45th president faces more legal jeopardy than the socialist but shares his defiant streak.

President Trump, fighting multiple indictments and possibly facing more, may spend Election Day 2024 in prison, but don’t expect incarceration to end his candidacy. Instead, look for him to follow the path of the celebrated Socialist Party candidate, Eugene V. Debs, 100 years ago.

In the 1920 election, Americans had just emerged from a global pandemic and World War I. President Wilson, a Democrat, used the occasion to target political opponents. Risking prosecution, Debs spoke out against “Mr. Wilson’s War,” saying that American boys were “fit for something better than cannon fodder.”

“I may not be able to say all I think,” Debs told the crowd at Canton, Ohio, President McKinley’s hometown, “but I am not going to say anything that I do not think. I would a thousand times rather be a free soul in jail than to be a sycophant and coward in the streets.”

Wilson won reelection in 1916 on the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War” but plunged the nation into Europe’s fight thirty days after delivering his second inaugural. When military recruiting lagged, he imposed a draft and cracked down on men who balked.

Debs responded that the government could arrest the resisters, “but they cannot put the socialist movement in jail.” He was then prosecuted under Wilson’s Sedition Act of 1917. Born out of the same Espionage Act that Mr. Trump is charged with violating by mishandling classified documents, the law made it a crime to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the United States government.”

The indictment accused Debs of sedition by “uttering language intending to incite, provoke, and encourage resistance to the United States.” The Sun described his actions as having “endeavored to destroy the government.” Both foretell the charges leveled at Mr. Trump.

Richard Lovelace, an English poet also imprisoned for protesting his government, wrote, “Stone walls do not a prison make nor iron bars a cage.” Debs might have used the line as his campaign motto, telling the court that he wouldn’t retract a single word even if he died in jail.

Saying, “I ask for no mercy,” Debs was sentenced to ten years in the big house. Mr. Trump faces more legal jeopardy than the socialist but shares his defiant streak. “I enter the prison door a flaming revolutionist,” the Sun quoted Debs as saying when he entered prison, “my head unbent, my spirit untamed, my soul unconquerable.”

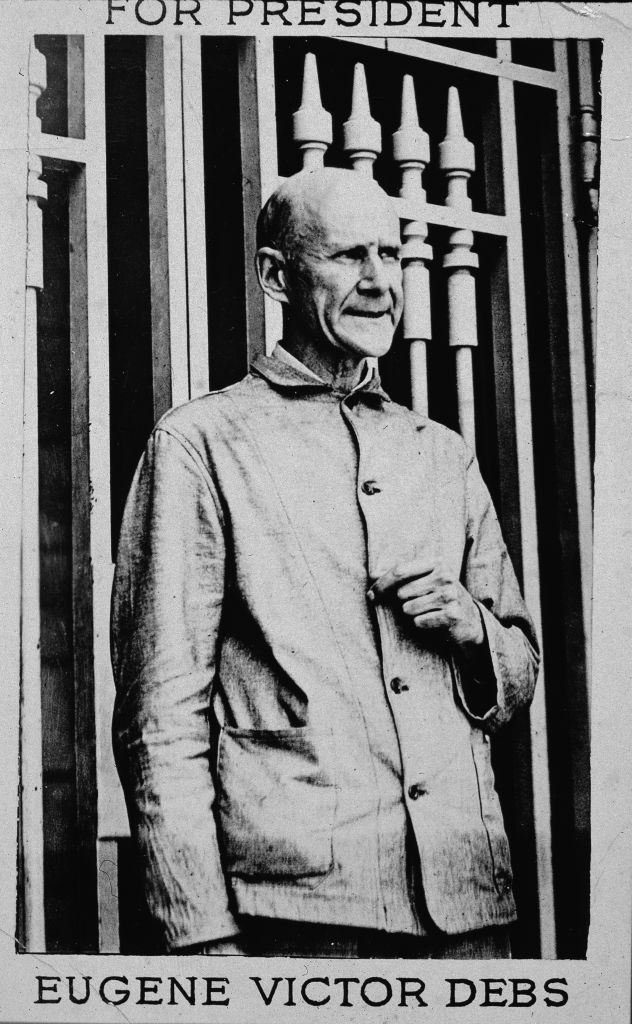

The Socialist Party nominated “Convict 2253,” as Debs denominated, for the presidency, delivering the honor at the federal penitentiary before newsreel cameras and printing his prison number on campaign buttons. His 3.4 percent of the vote on Election Day wasn’t close to victory, but his defiance caught the eye of the man who replaced Wilson.

Over 60 percent of Americans pulled the lever for President Harding, a conservative Republican who promised a “Return to Normalcy,” the same phrase Mr. Biden appropriated in 2020. The Sedition Act was repealed six weeks after Harding’s landslide and, two days before Christmas 1921, he commuted the sentences of Debs and twenty-three other political prisoners.

“I thought the spirit of clemency was quite in harmony with the things we were trying to do in Washington,” Harding said, “that Debs had never been guilty of any overt act, that he never countenanced destruction of government by force, and probably I could persuade him to become a factor in contributing to tranquility throughout the land.”

In an era when, like ours, Americans feared political violence — an anarchist assassinated McKinley in 1901 — freeing Debs and inviting him to the White House were bold moves to bind up the nation’s wounds rather than exploit them. The 29th president told Debs, “I am now glad to meet you,” and Debs praised the president as “a kind gentleman, one whom I believe possesses humane impulses.”

Just as prosecution put wind in Debs’s sails, Mr. Trump revels in drawing the government’s ire. In a speech on Sunday at Montgomery, Alabama, he called the three indictments against him “a badge of honor” and said, “One more indictment and this election is closed out.”

Thursday’s Reuters/Ipsos poll finds that Mr. Trump suffered no loss of support after his latest arrest. Last week’s New York Times/Siena poll found him tied with Mr. Biden. To win back the White House after a conviction, he would have to stump the trail Debs blazed a century ago and prove that stone walls and iron bars can cage a candidate, but are little good at containing his message.