New York Mayor Could Lose Control of Sprawling School System Unless Governor Acts

City schools could see a return to a system of governance involving 32 separate community boards and a weakened Panel for Educational Policy.

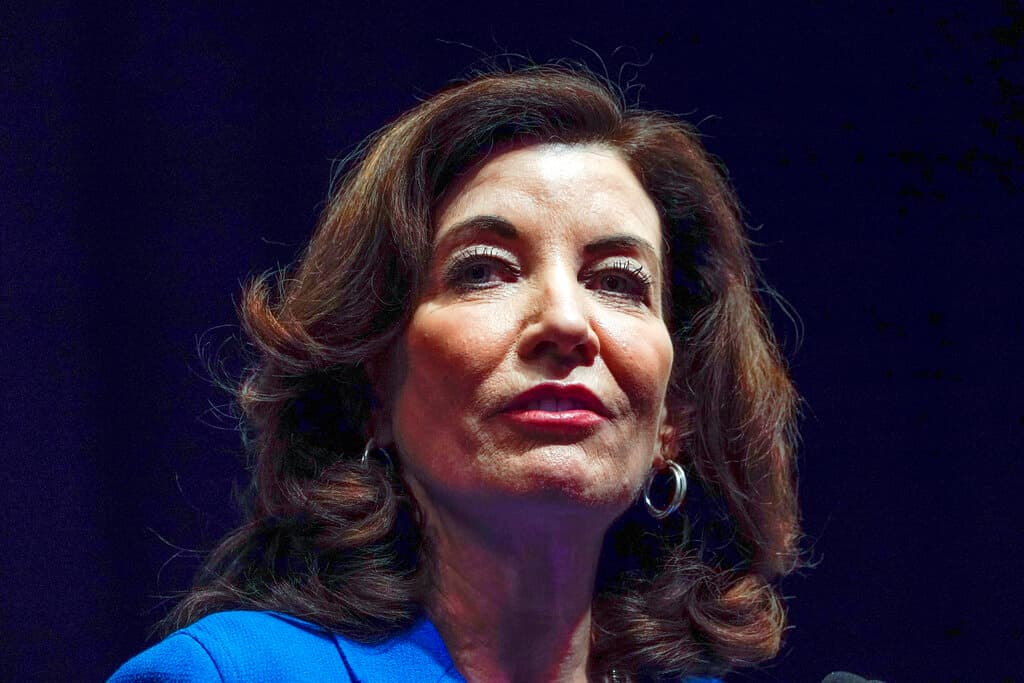

New York City’s mayoral control mandate that gives Mayor Adams power over the country’s largest school district is set to expire Thursday unless the Governor Hochul intervenes, an outcome that would see a return to an unwieldy, decentralized system that was left behind 30 years ago.

In April, Mrs. Hochul pledged unequivocally to extend mayoral control. As of Thursday evening, she had yet to do so.

If it is allowed to expire, New York schools could revert to a system of governance in which 32 separate community boards and a weakened Panel for Educational Policy — the school district’s main governing body, akin to the school boards seen elsewhere — managed the district’s 1,851 schools and the more than one million students they serve.

“Going back to a system in which you don’t have one person accountable and in charge — meaning the mayor — would be a disaster,” the director of education policy at the conservative-leaning Manhattan Institute, Ray Domanico, said. “The previous 30 years of history in New York City under decentralized control were a mess.”

The state legislature last month passed a measure to renew the mayoral mandate, but in a diluted form. Under the bill, the mayor would face more constraints on his ability to appoint people to the Panel for Educational Policy. The panel approves all contracts, oversees funding allocations within the Department of Education, and sets major policies for governance of the schools.

Currently, the mayor makes the majority of appointments and can recall appointees at his discretion. The panel is now made up of nine mayoral appointees, five appointees named by the city’s borough presidents, and one member elected by presidents of local school advisory boards. The mayor’s supermajority usually guarantees his agenda will pass.

Under the bill that Ms. Hochul has yet to sign, the mayor would appoint 13 of an expanded board’s 24 members, and there would be five appointees selected by the local advisory boards, one for each of the city’s five boroughs.

The bill would put restrictions on whom the mayor could appoint to the panel. Four of his appointees would need to be public school parents, and at least two appointees would be parents of children with special needs — one with an individualized learning program and one in a District 75 school for more severe learning disabilities. Additionally, one appointee would need to be a parent of a bilingual student or one who speaks English as a second language.

Members of the new, 24-member panel would also have fixed terms. Each member would serve a one-year term, and appointments could not be revoked if a member voted against the agenda of the mayor or whomever made the appointment — something that occurred in both the de Blasio and Bloomberg administrations.

The mayoral control extension was accompanied by another bill that would require New York City to lower class sizes over the next five years. Legislators insisted that the renewal of mayoral control was dependent on inclusion of this caveat in the bill.

Both Ms. Hochul and Mr. Adams advocated for stronger mayoral control and a longer extension. Ms. Hochul initially included a four-year extension of the current form of mayoral control in her 2022-23 executive budget proposal, but the legislature nixed it.

Mr. Adams criticized the legislature after the passage of the bill in May, calling legislators who opposed his plan “professional naysayers.”

“We need mayoral accountability,” Mr. Adams said. “We need it to stabilize a school system that’s dysfunctional.

“If you want to water it down, if you take away the tools that we need, if you don’t give us the opportunity to do so, then we are failing our children again and we’re going to have another generation of children who are not prepared to fill the jobs and be able to deal with the crisis that we’re facing,” he said.