In Argentina, a Population Tries To Cope With 100 Percent Inflation

Instead of panicking, Argentinians’ relationship with inflation has been one of adaptation.

BUENOS AIRES — With Argentinians facing some of the worst inflation rates they have seen in 30 years, locals crowd the stores at Buenos Aires and queue outside high-end restaurants to get rid of their pesos. The preference is for instant gratification rather than saving.

Argentinians can’t buy a motorcycle, a car, a property, or vacation at their preferred holiday destinations, so they decide to spend their money and try out new restaurants instead, the owner of one, La Pipeta, Jorge Ferrari, told The New York Sun.

Argentina’s annual inflation rate is now 114 percent. The local currency, the peso, has lost half its value in the last 12 months. Millions rely on the black market to buy American dollars to evade government restrictions. As the economic crisis deepens, local salaries decrease in value every month.

Federico Frutos, who is 32 and owns a restaurant, Alfonso, at the City of Buenos Aires, said this is the reality for him and his friends. He could save for the future by changing 50,000 pesos — considered a large sum of money in Argentina — into about $100. Instead, he prefers to go out with his friends and enjoy a good meal.

Juana Pita, who is an employee at Alfonso, agrees. She said she enjoys inviting her loved ones out for dinner or coffee. “In the middle of the economic chaos, it’s like coming out for fresh air,” she said.

The average monthly salary for those in the public sector in the second trimester of 2023 was 422,000 pesos, or about 850 American dollars, according to government data. For people ages 18 to 34, the average salary is closer to 267,000 pesos, or about $540.

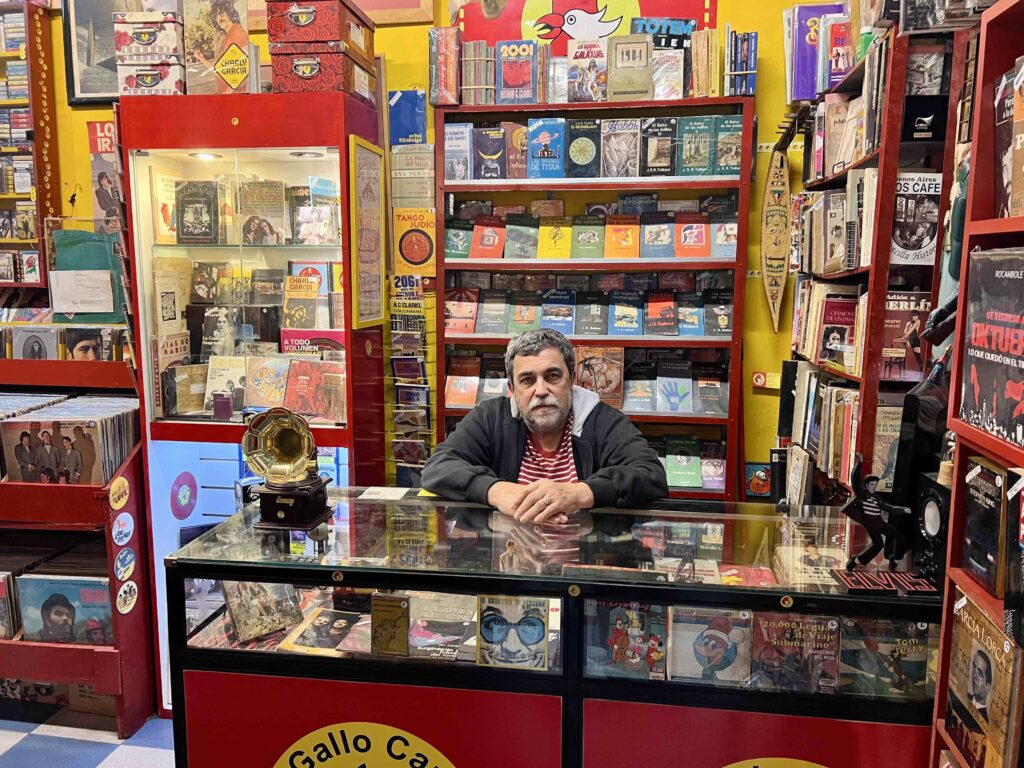

It’s not as bad to have a business in Argentina at the moment, the owner of a record store, El Gallo Cantor, Hugo Latorre, told the Sun. “People want to get rid of their pesos,” he added, because they are acutely aware their money won’t be worth much next month.

“In this crisis I prefer to buy than to save money,” Mr. Latorre said. “Because something worse than not having money for a business is not having products.”

Instead of panicking, Argentinians’ relationship with inflation has been one of adaptation. Unlike in America, most Argentines don’t have access to credit; they pay for everything in three, six, or 12 installments. Some don’t trust banks. They use everything from old jackets at the backs of their closets to bed mattresses to store their savings.

The monthly inflation rate in Argentina has averaged 8 percent in the first six months of the year, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina. Some business owners update their prices as often as every 10 days.

In order to avoid the hassle of updating the prices of every record, Mr. Latorre created a system in which he marks the products in his store with a letter. Customers can see signs around the place with the current costs of the products in each category. “Inflation is so high that instead of changing the prices of the 5,000 records each month, I just change the signs,” Mr. Latorre said.

Argentina is no stranger to inflation. During the last 100 years, the average inflation annual rate in the country has been 105 percent, with the maximum being 3,079 percent in 1989, under the presidency of Raul Alfonsin, according to a report in 2018 from the Argentina Chamber of Commerce and Services. During this time, Mr. Ferrari recalls, he had to increase prices about five or six times a day.

The key to navigating this economic rollercoaster, Mr. Ferrari said, is to be aware that Argentina’s economy can collapse at any moment, bringing an unexpected crisis to his business. Take many risks, Mr. Ferrari said, but make sure to drive with “no bumper and no seat belt. If you crash, you are able to fly out.”

In addition to President Alfonsin’s hyperinflation, he recalls the 2001 economic crisis and the pandemic as the moments that were significant to his business and his life.

It’s like Argentines have gotten used to living in this rollercoaster of economy, the owner of the San Telmo-based hat store La Sombra del Arrabal, Miguel Oziel, tells the Sun. “Compared to other places, Argentinians are accustomed to living with inflation,” he said.

Mr. Oziel opened his business 20 years ago. He remembers when, in April, the black market dollar — the currency in which Argentinians save — jumped to 495 pesos from 394 in 13 days. As a consequence, businesses were on edge. The uncertainty of not knowing what was going to happen the next day flooded the streets. Some didn’t want to sell their products, Mr. Oziel said. Others went as far as closing for that period of time.

To have a store in Argentina’s economy, he adds, one must take these extra precautions. “It’s something that we all do, even though some don’t openly say it,” Mr. Oziel said. “The problem in Argentina is that we don’t see continuity, we don’t have stability.”

About 60 percent of Argentinians consider inflation their biggest concern, according to a study conducted by Synopsis. Corruption is next on the list, at 27 percent. These are the two main drivers for voters in the upcoming presidential elections, expected in October.

Despite the overwhelming inflation and the uncertainty of the upcoming elections, there is another reason why restaurants and bars are crowded: Argentinians seek to nurture their connections. It’s a society driven by the need to connect with family, friends, and loved ones.

After being restricted from physically being with their loved ones during the pandemic, Argentinians are now using their resources to reconnect. “The Argentine is a very social person,” Mr. Ferrari said. “It needs to go out and build those connections.”