How Chinese Spies and Influencers Threaten U.S. Policy and Government

The FBI has thousands of open Chinese intelligence investigations spanning every one of its 56 domestic field offices.

For more than a decade, Linda Sun served in sensitive positions in New York State government, including deputy chief of staff for Governor Hochul and an aide in the administration of Ms. Hochul’s predecessor, Governor Cuomo. For at least some of that time, Ms. Sun and her husband, Chris Hu, are alleged to have acted as undisclosed — and well-compensated — agents for the People’s Republic of China.

When it comes to China’s secret operations on American soil, it isn’t always about tried-and-true espionage. A longtime China intelligence expert, Matthew Brazil, who is a senior fellow at the Jamestown Foundation, told The New York Sun that Ms. Sun is accused of activities “that seem more like an agent of influence rather than those of an intelligence asset.”

The allegations against Ms. Sun “include keeping Taiwan officials out of New York State events and steering State government attention” toward activities and events of the People’s Republic of China, he said. “An operation like that undermines United States policy of maintaining public contact with Taiwan authorities and can shape United States public opinion against our national interests of maintaining a free Taiwan.”

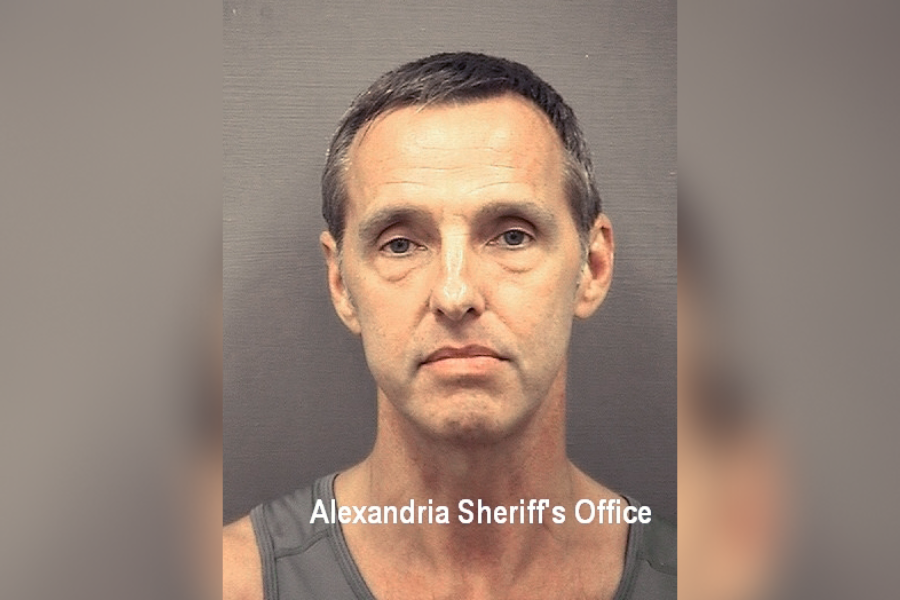

Ms. Sun is hardly the first, and will not be the last, alleged Chinese insider to have infiltrated the inner workings of the United States government. In 2019, Virginia-based United States intelligence officer, Kevin Patrick Mallory, who worked across multiple government agencies, was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Mr. Mallory was convicted under the Espionage Act for conspiracy to transmit national defense information to an agent of the People’s Republic of China.

The following year, it was disclosed that a suspected Chinese intelligence operative, Fang Fang, also known as Christine Fang, had penetrated the 2014 re-election campaign of a Democratic representative of California, Eric Swalwell. Once she realized she was being investigated, she fled the country in 2015, presumably headed back to China.

In September 2024, a former Central Intelligence Agency officer, Alexander Yuk Ching Ma, was sentenced to ten years behind bars for working as a double agent to China.

This barely scratches the surface. A 2021 report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies identified 160 incidents of Chinese espionage against the United States since 2000, with a sharp increase in activity after 2010. Based on open-source data, the report likely underestimates the true number of cases. The Federal Bureau of Investigation has thousands of open Chinese intelligence investigations spanning every one of its 56 domestic field offices. In 2021, the bureau divulged it was opening at least two China-connected investigations daily.

The chief executive of risk and counterintelligence firm Black Ops, Casey Fleming, told the Sun that such cases become known to law enforcement when a suspicious colleague alerts the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He cautioned that for every spy or influencer caught, many more go undetected.

“Our estimate is only 1 to 2 percent are brought to justice,” he observed.

Mr. Brazil pointed out that it is impossible to know how many Chinese Communist Party intelligence officers and agents and how many influence agents are active in America because “the only ones we in the unclassified world know of are those that have been convicted,” Mr. Brazil pointed out.

It appears, though, that operations of the Ministry of State Security and United Front Work Department, a Chinese intelligence-gathering body, have “gradually expanded” operations worldwide “since Xi Jinping was elevated to party and national leadership in 2012,” Mr. Brazil noted.

Why it Matters to Washington

Chinese espionage and covert influence on American soil have emerged as among the country’s most destructive national security threats. Washington is especially concerned about increased efforts by China’s Ministry of State Security to place and recruit assets across various levels of government and the intelligence community, jeopardizing trade secrets, defense, jobs and human life.

Mr. Fleming stressed that Chinese spies and influencers across America are “extremely widespread, beyond imagination.” He noted that this is the result of decades of infiltration and the notion that in China, it is considered your national duty to spy — an obligation often also placed on Chinese Americans.

Under laws enacted under President Xi, Chinese businesses are obligated to cooperate with intelligence agencies when asked. This is a stark contrast to America, where the government does not engage in industrial espionage to benefit private companies.

“All sectors (in the United States) are targeted with an emphasis on theft of intellectual property in technology, military, healthcare, and even agriculture. These spies exhibit a maximum-security threat,” Mr. Fleming continued, adding that using human informants is a “highly accurate intelligence method.”

Beijing utilizes an array of tools, from spy balloons to cyberattacks to buying up land near critical infrastructure, yet human intelligence is the most potent weapon in its arsenal.

Starting in 2005, while Washington was distracted by the burgeoning War on Terror, the Ministry of State Security proclaimed its own war on Washington’s intelligence apparatus and devoted its prime personnel and resources to the United States government and intelligence agencies.

Mr. Fleming told the Sun that Beijing’s first goal is to “extract all key intellectual property to power the Chinese economy and military and remove it from U.S. national security. “

“Its (second objective) is to prepare for conventional war with the U.S. and the free world,” he continued. “Freedom is the largest threat to communism.”

Beyond the Government

Chinese assets have also breached other critical sectors, including academia, technology, and business.

In 2022, Chinese intelligence operative Yanjun Xu was handed a 20-year prison stint for posing as a businessman to steal American aviation trade secrets. In January this year, a former graduate student at Chicago, Ji Chaoqun — who came to America to study electrical engineering and later enlisted in the Army Reserves — was sentenced to an eight-year prison term for collecting information on engineers and scientists on behalf of the Chinese government.

The following month, husband-and-wife duo Li Chen and Yu Zhou were sentenced to several years for conspiring not to steal national security secrets but innovations in pediatric cancer research at Beijing’s behest. Then, a federal grand jury accused Linwei Ding of stealing trade secrets from Google in March. The indictment alleges that Ding was involved in a plot to acquire proprietary information related to Google’s artificial intelligence technology for the Chinese government.

The industrial sectors are especially vulnerable to technology and trade secret theft, especially technologies that are difficult to obtain in China, such as computer chips, underwater connectors, high-grade steel and mobile phone components.

“There is a heavy emphasis on technology acquisition, but also on a historical mission to do what all spies do – obtain classified information of relevance to decision-making by their political masters,” Mr. Brazil explained.

He surmised that Beijing’s agencies “have been particularly successful in cyber operations, vacuuming up massive amounts of data” not only from the famous OPM hack a decade ago but, more recently, from unclassified American government emails.

Other American-based operatives function in more of a gray influence-pushing area.

In 2020, the Justice Department accused eight individuals of acting as agents of the Chinese government. These individuals allegedly targeted a New Jersey man sought by Beijing, attempting to pressure him to return to China to face charges. Last year, a New York-based academic, Shujun Wang, a naturalized American citizen, was convicted of covertly acting as an agent for the Chinese government, infiltrating pro-democracy groups, and providing intelligence on Chinese dissidents in America — endangering family members in mainland China.

Mr. Brazil also pointed out that Chinese operatives have been busily snatching trade secret data from private companies and information useful against emigre populations abroad, particularly on the activities and identities of Chinese democracy activists and the Uyghur and Tibetan minorities outside of China.

The Recruitment Process

The Ministry of State Security generally acquires its operatives, including Americans and individuals without obvious ties to China, through methods beyond deploying Chinese nationals specifically for spying purposes.

Chinese agents are known to use social networking sites, primarily LinkedIn, to target those in the intelligence and defense sectors with seemingly valid — and benign — business and contracting opportunities, as in the case of Mr. Mallory, who was contacted in 2017 over the professional networking site by a person purporting to represent a Chinese think tank known as the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. These apparent consulting offers function as an initial way in, opening the door for further exploitation and enabling intelligence officers to determine the appropriate motive for a prospective recruit, ranging from money, ideology, coercion, and ego.

China also uses ideology and coercion to recruit Chinese for espionage and influence agents abroad, but when it comes to grooming Westerners, financial incentives are typically the most effective. A former Defense Intelligence Agency officer, Rockwell Hansen, for one, was arrested in 2018 after receiving more than $800,000 from Chinese officials over four years. In 2019, he pleaded guilty to espionage-related charges and was sentenced to ten years in prison for passing sensitive military and cybersecurity information to China.

Washington’s Response

The American government is taking the matter seriously. In recent years, the Central Intelligence Agency and the Department of Defense’s Intelligence Agency established new centers equipped with communications interception capabilities to counter Chinese spying. The Agency has also upped its China-related efforts under Director Burns, dedicating more resources and personnel to the issue.

The renewed focus isn’t without criticism. Some, including 177 faculty members across 40 departments at Stanford University who wrote a protest letter to the Department of Justice in 2021, claim the counterintelligence ventures are racially discriminatory and excessive. Such condemnation resulted in the 2022 shuttering of the Trump administration’s China Initiative; a Justice Department program devoted to combating Beijing’s espionage in America.

From Mr. Fleming’s purview, however, excessive cultural sensitivities hamper the effort to counter China’s meddling in the West, and he asserted that more should — and could — be done, starting with building a broader national understanding of the threat.

“This war is unique,” he added. American citizens and their families are on “the front lines” against the Chinese Communist Party and nations aligned (against) the United States,” he added. The “ military is there as well, in the background.”