How About James Bond as a Central Banker? ‘Goldfinger’ Emerges as a Metaphor for Our Times

‘They get what they want — economic chaos in the West — and the value of your gold increases many times.’

Growing protectionism and what it portends for global economic growth — not to mention geopolitical stability — induces somber references to the year 1944. The “rules-based” Bretton Woods agreement hammered out by the Allies in July that year, while World War II still raged, puts into sharp relief the consequences of trade and currency wars.

Yet we don’t have to go back 80 years to make the point that having a stable monetary foundation to support free trade and capital flows helps to strengthen economic and political alliances. It was in 1964, only sixty years ago, that “Goldfinger” premiered with Sean Connery starring as James Bond. Monetary economists of a certain age will no doubt recall with pleasure this action thriller.

It features an MI6 agent who gets to the bottom of a diabolical plan to destabilize the Western financial system by irradiating the gold holdings of the United States. In other words, the linchpin for the successful rules-based approach that prevailed in the postwar era was the film’s main plot device. If that seems implausible, consider the most important rule governing the post-war international monetary system.

That was the commitment of the United States to convert United States dollars into gold at the rate of $35 an ounce. In exchange for this convertibility privilege, the central banks of participating nations were required to maintain their own currencies at a fixed exchange rate against the dollar.

In short, the gold-convertible dollar provided the anchor for international monetary stability. The aim was to ensure that the economic nightmare of the 1930s — during which peaceful world relations succumbed to the downward spiral of currency devaluations and retaliatory tariffs — a level monetary playing field for international trade and investment was established.

Bolstered by the Marshall Plan, which helped European countries rebuild their war-torn economies, the Bretton Woods international monetary system delivered impressive economic gains in growth and productivity for the United States and Western Europe. No wonder the villains of “Goldfinger” were eager to disrupt this happy monetary arrangement.

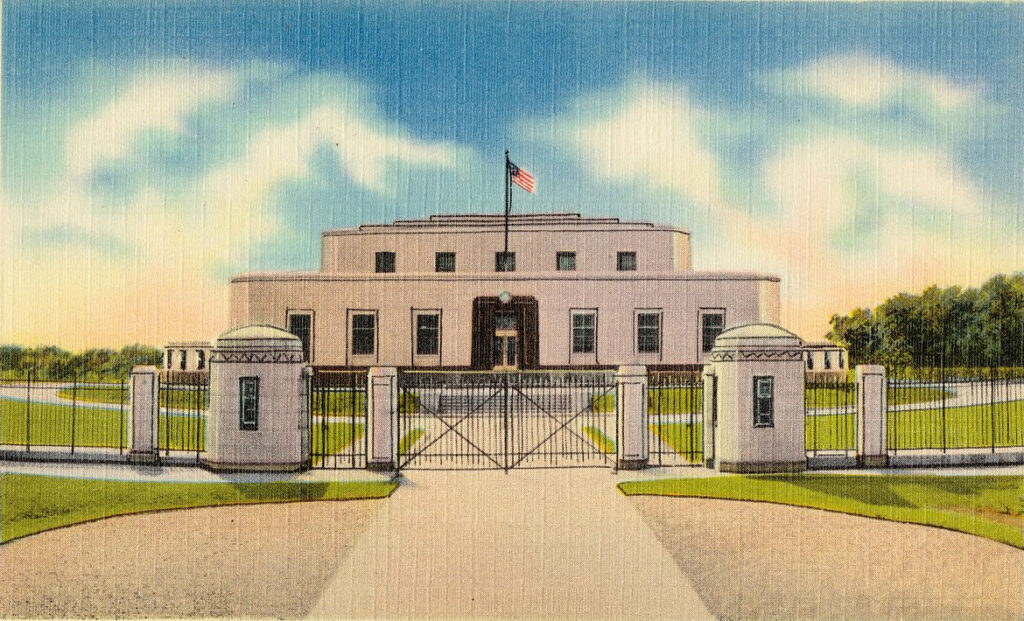

In the film, which features a nearly nude woman painted gold (causing asphyxiation), a European business magnate named Auric Goldfinger seeks to enhance the market price of his own gold holdings by rendering worthless the American government’s gold reserves stored at the bullion depository at Fort Knox. Agent 007 overhears Goldfinger talking with a Chinese nuclear physicist about “Operation Grand Slam” and surmises that China has supplied Goldfinger with a dirty bomb to detonate inside the vault.

In a conversation over mint juleps, Bond, who remains suave and composed after having narrowly avoided emasculation by laser beam, calculates aloud that if the cobalt-and-iodine bomb from China explodes in Fort Knox, “…the entire gold supply of the United States will be radioactive for fifty-seven years.”

“Fifty-eight, to be exact,” Mr. Goldfinger responds coolly.

“I apologize, Goldfinger,” Bond exclaims, genuinely impressed.

“It’s an inspired deal. They get what they want — economic chaos in the West — and the value of your gold increases many times.” The plan gets foiled, of course, through the daring interventions of Bond, assisted by pilot Pussy Galore and her Flying Circus, working in tandem with on-site American troops.

Through the magic of moviedom, the Bretton Woods system was allowed to prevail over evil. As it turns out, however, the gold that functioned as its bulwark was indeed rendered unusable just seven years later. On August 15, 1971, President Nixon suspended the gold convertibility privilege — ending the era of monetary stability both at home and abroad.

Floating exchange rates entered the void with devastating consequences; the price of dollar-denominated oil skyrocketed, government deficit spending exploded, inflation took its stubborn hold, and central banks became the only game in town. And three generations later, financial crises and new trade conflicts now loom on the horizon.

Today’s monetary “non-system” is dangerously vulnerable to that earlier syndrome of beggar-thy-neighbor policies. In the absence of any rules-based approach or inherent mechanism for restricting the issuance of money, central banks are not constrained to uphold exchange-rate stability for the sake of fairness in the global marketplace. Tariffs are the weapon of choice against perceived currency manipulators.

All of which poses a danger beyond the capabilities of even the most savvy of operatives to resolve. History has shown that friendly relations among trade partners can fall victim to bickering, rivalry and protectionism — potentially leading to a breakdown of geopolitical alliances. Diabolical, indeed.

Ms. Shelton’s new book, ‘Good as Gold: How to Unleash the Power of Sound Money,’ will be published on October 8.