High-Level American Diplomacy Focusing on Relations With Communist China, India

Expect widely different outcomes from Secretary Blinken’s visit to Beijing and the arrival of the Indian prime minister in America.

American leaders next week will be courting the governments of the world’s two most populated countries — a Communist giant that’s challenging American interests everywhere and the world’s biggest democracy.

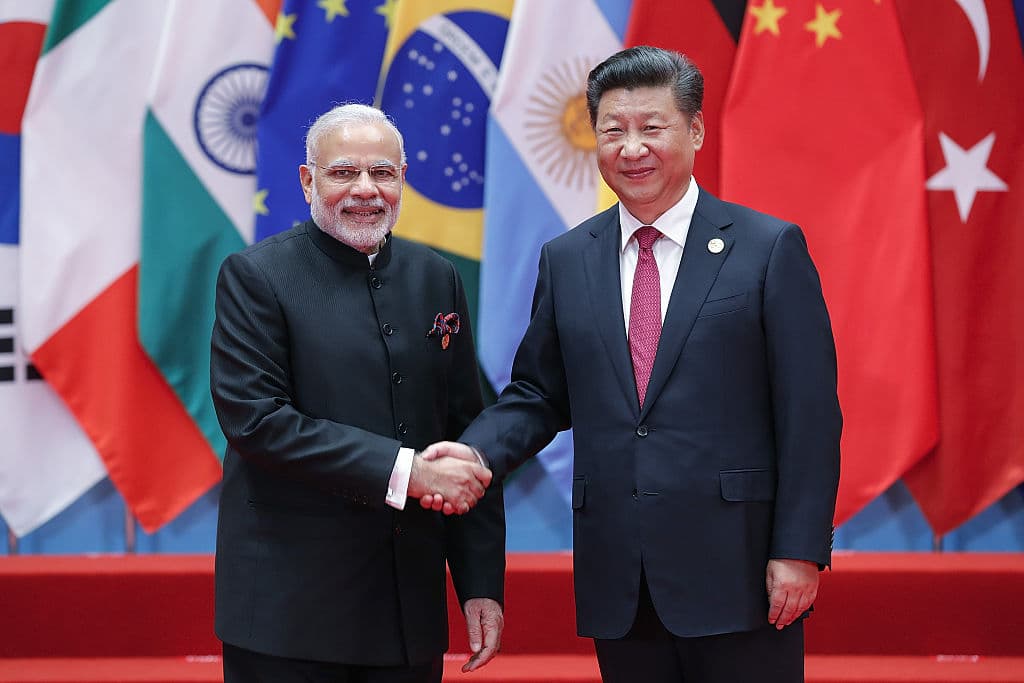

Secretary Blinken, in talks Sunday and Monday at Beijing, has hopes of putting a damper on rising tensions between the two countries; he believes improved “communications” may help. Four days later, President Biden hosts India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, in an attempt to elevate Indian-American relations to a new level as a foil against China.

It’s easy to predict that Mr. Blinken, during the Biden administration’s first visit by a top American emissary to the Communist Chinese capital, won’t get anywhere in changing Chinese policy on anything from Taiwan to espionage. In fact, he’d be lucky to head off open clashes around Taiwan and the South China Sea.

The assistant secretary of state for the region, Daniel Kritenbrink, set the tone for diminished expectations, saying both sides “have indicated a shared interest in making sure that we have communication channels open and that we do everything possible to reduce the risk of miscalculation.”

That’s not exactly a dramatic expression of optimism after China’s foreign minister, Qin Gang, in a phone conversation with Mr. Blinken, left no doubt China will keep up the pressure on the independent island democracy of Taiwan. America, he warned, must “stop interfering in China’s internal affairs, and stop harming China’s sovereignty, security, and development interests in the name of competition.”

India is a different story. America has come to regard that country as a pillar of democratic defense holding down its end of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad Four, that also includes Australia and Japan. While America is supporting India with transport aircraft and intelligence in clashes with China, India is buying critical military gear and technology, including drones.

India, though, is no pushover for those still hoping it might join the club opposing the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“India’s response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been distinctive among the major democracies and among U.S. strategic partners,” a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment, Ashley Tellis, writes. “Despite its discomfort with Moscow’s war, New Delhi has adopted a studied public neutrality toward Russia.”

In so doing, India “has abstained from successive votes in the UN Security Council, General Assembly, and Human Rights Council that condemned Russian aggression in Ukraine,” Mr. Tellis notes, while refusing “to openly call out Russia as the instigator of the crisis.”

Like China, India is not going to change its policy at Washington’s bidding. Nor is India likely to uphold democratic ideals as much as Americans might like. Since becoming prime minister in 2014, Mr. Modi, a Hindu nationalist, has steadily tightened control, repressing Muslims at odds with the nation’s Hindu majority.

“India’s status as a democracy has become increasingly suspect,” a research professor at Johns Hopkins University, Daniel Markey, writes in Foreign Affairs. “India’s neutrality has been disappointing. … Indian strategic elites would admit that their country’s diplomatic neutrality ultimately signifies what one Indian scholar has called “a subtle pro-Moscow position.”

Nonetheless, the optics surrounding the visits of Mr. Blinken to Beijing and Mr. Modi to Washington will be vastly different.

For starters, Mr. Blinken may not even get to shake hands with President Xi, whom he was to have seen in February before he canceled his visit after the Chinese were discovered to have sent a spy balloon over North America. Now China is portraying the Americans as eager to pay homage to the ancient “middle kingdom” while burdened with so many problems at home.

Like the Americans, “Chinese experts also have low expectations,” the Global Times, an instrument of the ruling Communist Party, said. America, it said, sees the visit as a “‘window of opportunity’ to save bilateral ties from deteriorating to ‘worse than the worst.’”

Mr. Blinken will get back in time for Mr. Modi’s visit that begins at New York on Wednesday, when the Indian leader joins in International Yoga Day at the United Nations. He’s “a known yoga practitioner,” according to an Indian announcement.

Next day, Thursday, the White House pulls out all the stops, greeting Mr. Modi with a 21-gun salute. He’ll address a joint session of Congress before chatting one-on-one with Mr. Biden, followed by a state dinner at which he may find it impolitic to suggest any doubts about supporting the NATO alliance in Ukraine.

If Mr. Modi remains ambivalent about Ukraine, in practical terms he’ll build on the visit of Secretary Austin to India earlier this month. America and India are expected to work on technology deals, talk about joint production of jet engines, and discuss defense against China from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas.

The White House adviser on the Indo-Pacific, Kurt Campbell, was full of optimism. Ultimately, he said, India will be “part of a strategy to diversify globally new supply chains, new investment opportunities,”

As for China, at best Mr. Blinken is hoping communications will forestall dangerous encounters between Chinese and American ships and planes in the Taiwan Straits and the South China Sea.

Mr. Blinken is also expected to express concerns about Chinese intelligence-gathering worldwide, including from a new installation in Cuba that’s spying on American bases, but the Chinese are sure to respond with firm denials. For him, hosting Mr. Modi at a luncheon Friday at the state department should come as a distinct relief after the shrugs and cold shoulders he’ll be getting in Beijing.

The name of the Global Times has been corrected from the bulldog.