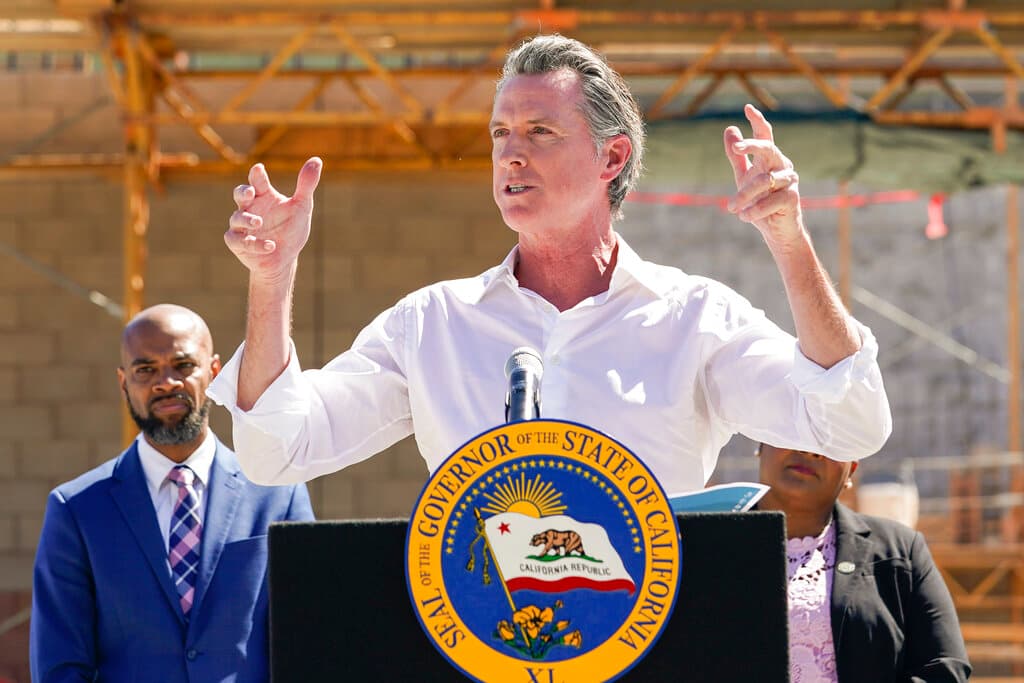

Governor Newsom’s White House Ambitions Could Be Behind Effort To Crack Down on Crime on the Coast

The Democrat faces a political liability in the form of his state’s dysfunction, as California cities are increasingly overtaken by the problems of crime and homelessness.

If Governor Newsom signs a bill making it easier to temporarily detain mentally ill and drug-addicted people, it could be a part of his strategy to address crime and homelessness in California as he eyes a run for the White House.

Mr. Newsom — whose national campaigning for Democratic causes has earned him the status of “the most visible Democrat-in-waiting” — faces a political liability in the form of his state’s dysfunction, as California cities are increasingly plagued with the problems of drug addiction and overdoses.

The governor previously has shown signs of pivoting from the liberal orthodoxy on drug policy and crime, last year vetoing a bill to legalize safe drug consumption sites and last week pledging to direct $267 million to law enforcement to crack down on crime.

Now, a bill sits on Mr. Newsom’s desk that, if signed, would expand the definition of “gravely disabled” to include individuals with substance abuse disorders and severe mental health disorders, making it easier to place them in involuntary holds or conservatorships.

Advocates argue that the bill would help those who are suffering and unable to seek aid, while opponents warn it is rife with potential for government abuse.

“I spent six months living on the streets of San Francisco addicted to heroin and fentanyl. I ended up going to jail where I got clean,” a recovery advocate, Tom Wolf, who has been sober for five years after entering a residential treatment program, tells the Sun. “I support this bill.”

The bill is “a first” and “absolutely necessary,” he adds. When he was living on the street, Mr. Wolf says he knew a man named Sam who suffered from schizophrenia, drug addiction, and necrosis — a condition that made his flesh rot off of his legs.

“He would go to the hospital periodically and they would treat him and then they would release him, right back out on the street into homelessness,” Mr. Wolf says. “And the smell that would permeate from his legs made him a pariah, people wouldn’t come within 10 feet of him because of the smell of rotting flesh,” Mr. Wolf says of Sam, who later died. “That person should be intervened upon.”

The civil rights groups that will likely pursue legal action against the bill are saying that a drug-addicted person in a similar situation “should be allowed to die with his rights on,” Mr. Wolf says.

The bill will likely be disputed in federal courts for years, Mr. Wolf notes, and the state of California in the meantime should work to build out more capacity for addiction recovery services.

The changes made in the bill are “about control and ostracization,” a senior advocate and researcher for Human Rights Watch, Olivia Ensign, tells the Sun. “It plays on prejudices against people who are living with mental health conditions to expand the state’s ability to involuntarily commit people to locked psychiatric facilities,” she says.

Some analysts warn that holding people involuntarily is ineffective and could lead to ethical issues. It “violates the sovereignty, autonomy, and agency of a person,” a Cato Institute senior fellow, Jeffrey Singer, tells the Sun. Compulsory treatment for both drug use and mental health issues doesn’t work and increases chances of harm, he adds.

“If you’re not addressing that problem and you just basically get a person so-called detoxed and abstinent, then when they’re released — since the underlying problems are still there — they tend to eventually go back to using the drug,” Dr. Singer says. “And since they’ve lost their tolerance, but they don’t realize that, they use the amount they used to take to get them the desired effect, and they have a much higher rate of overdose.”

Mr. Newsom is expected to sign the bill, which was passed unanimously by the legislature. A spokesman for his office tells the Sun that the governor has until October 14 to act on the legislation and that the bill will be evaluated “on its merits.”